The Story of White Pine, American Revolution, Lumberjacks, and Grizzly Bears Sam Cox History is often shaped by the smallest of living things. Plague, malaria, yellow fever and late blight of potato are all caused by almost invisible microbes that have each killed more humans than any, and maybe all, wars put together. Mankind is often the reactionary party to the offense put out by microbes, and sometimes he is a conspirator. Picture North America in 1500, before European colonization had even gotten a foothold on the continent, with its vast unbroken northern forests stretching like a green sheet over the water-carved landscape. Picture the current states of New England, where it was said by early explorers that a squirrel could go an entire lifetime without ever coming out of the trees. The dominant tree species in the old growth northeastern woods was called white pine by the first explorers, and later named Pinus strobus in the tradition of European Latin nomenclature. It is the tallest tree native to eastern forests, commonly reaching heights of 150 feet and circumferences at breast height of 15-20 feet prior to Europan colonization. A specimen at Dartmouth University in NH was reported to have attained a height of 240 feet. In comparison, the tallest Redwoods top out at around 380 feet. The current national champion White Pine is located in Michigan, with a height of 150 feet and a circumference of 18 feet. Eastern White Pine originally grew in pure stands, shading out the shade-intolerant firs and hardwoods to form a solid white pine canopy. Early settlers in New England marveled at the size of these trees which were far larger than anything left standing in Europe and the British Isles. White Pine has an upright, unbranching central trunk that grows remarkably straight and tall, a quality later to become very important in its history. In 1605, Captain George Weymouth of the British Royal Navy foresaw the potential usefulness of such tall and straight trees in the making of ship masts while cruising the New England coast and took seeds and mastwood samples back to England. The tree is known as Weymouth Pine in England to this day. The wood impressed the Naval Board for its combination of strength and light weight, however the planted seeds never performed as well in the English climate as they do in the eastern North America. England was desperate for a source of good mastwood because her own lands were, by the 16th century, almost entirely deforested. For that reason, England relied on European-grown Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris) for mastwood, which was shorter, heavier, weaker and had to be pieced together to make the large masts required for the massive warships of the era. Unfortunately, the most desirable specimens were grown in Russia, Prussia and Sweden, countries that could be, and were, blockaded by England’s ocean rival, Denmark, in times of open hostilities. This comprised the chief need for a new mastwood source. Back in New England, it did not take long for the commercial value of such massive trees to be realized, both as mastwood and raw lumber, and the first English lumber mill was built and put into service in 1623 in York, Maine. The vast virgin forest became a gold mine for the lumber mills, and provided New England with its first major industry. White Pine was the most desirable tree in the forest because of its combination of light weight and strength, and because it was very easy to cut and shape into furniture. Fortunately for the lumber mills, it was also the most abundant tree in the forest. The westward expansion into the forests began in earnest, and the forest was leveled in the lumberjack’s wake. The largest individuals were sold for masts, and sold for £100 a piece. Smaller trees were used to make furniture, bridges, houses, ships, looms, matches and just about anything else that was made of wood in those days and for the next two centuries. Probably no other tree has had such a great economic impact on a nation than that of the white pine on the United States. The first major trade pattern that the American colonies engaged in was a triangular trade fueled by white pine: New England white pine lumber to West Africa, African slaves to the West Indies, sugar and rum back to New England. Many fortunes were made on the planks of white pine. Even the ships that ferried the lumber were made of it. By the twilight of the 17th century, white pine had achieved singular economic importance in New England. John Josselyn’s “Account of Two Voyages to New England”, published in England in 1674, described at length the immense size and usefulness of white pine. As a nod to its importance, the white pine tree was depicted on the first New England Flag as early as 1686. As the economies of the English coloniesin North America improved

through increasing international trade, so too did the ability of the colonies

to resist the dominating British rule. When, in the 1750's, the King of

England proclaimed that the largest white pine specimens were reserved

for the crown, the trade of the monster specimens continued, only now with

the principal buyers being enemies of England (as virtually every western

power was during the latter half of the 18th century). Colonists continued

to clear the land to the west towards the Appalachians, selling the trees

to lumber mills and farming the rich soil left behind. The Crown pursued

the matter by appointing John Wentworth, then Royal Governor of the colony

of New Hampshire (and the last), to the position of Surveyor General of

His Majesty’s Woods in America, with authority to claim any tree on lands

granted to settlers or otherwise, in the name of the Crown. Such trees

were marked by a blaze called the King’s Broad Arrow. This claiming of

valuable economic resources infuriated those whose lives had come to be

closely intermingled with the trade in white pine. In New England and Maine

this act had the same effect as the Stamp and Townsend Acts were to have

in the cities further south. In 1761 the Crown declared that future land

grants would have a clause that any tree measuring 24 inches in diameter

at 12 inches height was property of the crown and that no timber harvests

could be carried out on such land by penalty of grant revocation. A spy

system was initiated whereby those who ratted on their disobedient neighbors

received their land. To circumvent this, colonists took to disguising themselves

as Indians and sawing down trees at night. A law was then passed whereby

anyone caught cutting trees in disguise would be flogged. This series of

punch and counterpunch illustrates how seriously this issue was regarded

by both sides. By the time the flogging edict came down, however, such

a law had become unenforceable, as the loss of recognized British authority

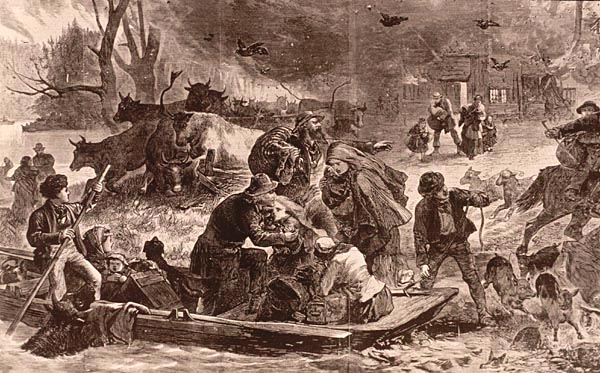

in the American colonies was Extensive logging followed the Revolution for 200 years, and the profits

expanded corporate influence in America and developed the first monopolies

of the timber barons in the 19th century. The Lumberjack earned his place

in the American lexicon as immigrant woodsmen from nordic regions of Europe

built up a mythology of brawn and toughness that is recognized and stereotyped

to this day. The extensive river network of New England facilitated the

transport of logs to the Atlantic coast where they could be shipped abroad.

In Wisconsin and Michigan, white pine logs were floated south to New Orleans.

One log raft that passed by Cincinnati in the late 1800's covered over

3 acres. By the turn of the century, almost all virgin white pine stands

had been logged and the land cleared for agricultural purposes. Attention

was turned to southern Appalachia where smaller stands of white pine still

existed. The big draw for the timber barons by then, The trail of destruction left behind across the northern woods in the wake of the lumbermill saw was monumental. Millions of square miles were leveled to the ground, denuded of all vegetation. Erosion was followed by colonization by aspen and fir trees and various species of shrubs. The prevalence of these fire-prone species, along with mountains of slash from old logging operations, set the stage for numerous raging fires in and around logging towns in the late 19th century. The logging town of Peshtigo, WI was obliterated, and 1200 people killed, in October 1871, marking the costliest fire in terms of human life in US history. The logging town of Hinckley, MN was similarly erased by fire in 1894. Erosion clogged waterways, and local economies collapsed after the local forest resources were exhausted and the timber companies moved on. Concern over the environmental and health impacts of unregulated logging led to the rise of the conservation movement, Theodore Roosevelt, national parks, and the salvation of much of the great western forests.  Owing to the ruthless efficiency of the lumber companies, by 1900 the Northeast had lost its most valuable resource..the white pine. Scores of hardwood species had replaced the white pine in its native range, and none were as valuable. Replanting efforts were sponsored by the US Forest Service, but American nurseries could not supply white pine seedlings on the scale required. Congress acted by lifting a tariff on imported plants that had previously inhibited the import of foreign-grown seedlings. The first Forest Chief, Gifford Pinchot, supplied Germany with millions of native seeds to grow in their established nurseries. In 1907 these seedlings began arriving in America with an unwelcome stowaway.

Not only was the fungus brought to America by humans, it was widely spread by the planting of diseased stock, and then introduced again on the western coast of America. A pathogen could ask for little more. North American was served up on a silver platter. Because of the destruction wrought by the pathogens that caused white pine blister rust and chestnut blight, Congress passed the Plant Quarantine Act in 1912 which was the first legilslation ever authored in an attempt to keep foreign pathogens out of the country. Many white pine trees have been found that possess varying degrees of resistance. The US and Canadian Forest Services have been working hard to breed this resistance into nursery stock. Since the 1950's, over 10,000 seedlings from resistant parents of western white pine have been screened at the USFS Dorena Genetic Research Center in the Northwest US, where 95% of seedlings died withing 5 years. Nevertheless, enough resistance has been found in the gene pool to make western white pine the only available rust-resistant 5-needled pine. Developing resistance in Sugar Pine and Eastern White Pine are priorities. Research into rust resistance has shown that a single dominant gene is responsible for rust resistance. Some groups are working at bringing that gene into species where it is not naturally occurring, but this sort of work is highly controversial. Similar research with hybrid poplar was the subject of destructive property attacks by ELF (Earth Liberation Front) in Wisconsin, Oregon and Washington. Sugar Pine has also been found to have some resistance. Whitebark pine has shown no appreciable resistance to the rust, and is in danger of being completely wiped out. Bristlecone pine tends to grow only in high elevation sites that are typically dry, which does not favor the fungus. This seems to protect most populations of bristlecone pine from infection. The greater threat to bristlecone pines seems to be something along the lines of the graduate student who cut down what is believed to be the oldest living tree in the world in order to retrieve a coring device that broke off inside the trunk. In Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, a section of the Pacific Crest Trail was found to have a 46% whitebark pine infection rate, with 92% of infected trees displaying advanced-stage lethal cankers. Whitebark pine populations in Glacier National Park, Montana have been severely impacted, with an estimated 89% of the entire population infected, 50% of which are already dead. Any visitor to the high country in Glacier finds it hard not to notice the stark white skeletons of whitebark pines that succumbed to the rust infection. Whitebark pine grows only in disturbed sites, such as in burn areas, so the National Park Service and Forest Service policy of fire suppression reduces the regeneration opportunity of this species. Fire intervals for whitebark pine ecosystems were historically 50-300 years, but are now estimated to be 3,000 years under current management practices. Since it is a matter of probability that resistant seedlings will emerge, fewer seedlings means less chance of resistant seedlings being discovered. Thus, once again, humans are undermining survival strategies of the pines. It is estimated that all Whitebark Pines in Glacier will be dead by 2015. The ecological impact of whitebark pine has received considerable attention because whitebark pine nuts comprise an estimated 40% of the Grizzly Bear’s fat requirement in the northern Rockies. Nuts are cached by Clark’s Nutcrackers and squirrels in hollow logs and stumps, and these caches are raided by Grizzlies in the fall just before winter hibernation to help the bears put on fat for the long winter. As these trees decline, the nut caches become scarce and Grizzlies are forced to look elsewhere for food, often leading them into lower elevation human settlements where they face extermination. Additionally, bears that do enter hibernation without adequate fat reserves face the possibility of dying during the winter. With Grizzly populations in the lower 48 states of the US already estimated to be below 1000, and with introduced legislation to remove the Grizzly from the Endangered Species list and allow it to be classified as a “Trophy Game Species”, the complete collapse of the white bark pine food supply could have disastrous consequences for the long term survival of the Grizzly Bear in the lower 48 states. For more details on management of White Pine Blister Rust, click HERE. In 1999, white pine blister rust was found near Red Feather Lakes in northern Colorado, a state that had miraculously remained free of the rust for half a century. The extensive population of limber pine (P. Flexilus), another susceptible 5-needled pine, in the high country of Colorado has many very worried about the ecological impacts this introduction could have. The Fort Collins Forest Service Branch is currently studying the spread of the rust through limber pine populations, but has little in the way of strategy to halt it. In the eastern US, white pine blister rust is still a major economic issue. The University of Minnesota received a $300,000 grant in the late 1990's to help find ways of reducing rust impacts on the mature second growth white pine timber stands in Minnesota. Clearly, white pine blister rust continues to be a problem almost a century after it was introduced to this country. Economic and ecological impacts are difficult to quantify with precision, but are obviously very high. Along with Chestnut Blight and Dutch Elm Disease, Blister Rust has taken its place as one of the most destructive pathogens of America’s most important and beautiful trees. Literature Cited Because this article is not intended for peer review but rather for general readership, I refrained from citing references in the text, deciding rather to simply list the group of sources at the end. I hope this will make the article more enjoyable and readable. All information contained in the article was derived from the following sources. Agrios, GN. 1978. Plant Pathology, 3rd ed. Academic Press,

San Diego.

Page

Created January 22, 2003

|

practically

complete. In 1774, shipments of white pine lumber to England were halted,

and in 1775, the American colonies made a bid for independance. The Massachusetts

Minutemen who fired the first shots of the American Revolution at Lexington

in April 1775 carried a flag of red with a green pine tree emblem on a

field of white with them into battle at Bunker Hill in June 1775, in what

was to be the bloodiest battle of the entire war. Almost concurrently,

several small clashes took place in Kennebec, Falmouth and Portsmouth,

Maine between American lumberjacks and British authorities, all related

to the requisition or seizure of white pine masts which the British Royal

Navy so desperately needed. The American Revolution was in fact only a

piece of a much larger European conflict, whereby Britain found herself

pitted against every other European military power. France assisted the

American colonies, not out of any inherent friendship with these upstart

democratic states (France herself at that time was a monarchy, like England)

but simply to apply pressure on her political and military rival. The French

ships that blockaded Yorktown against the British Navy and sealed General

Cornwallis’ fate against the surrounding American forces all had white

pine masts courtesy of New England. It was one of the few moments in pre-industrial

history when the British Royal Navy was

practically

complete. In 1774, shipments of white pine lumber to England were halted,

and in 1775, the American colonies made a bid for independance. The Massachusetts

Minutemen who fired the first shots of the American Revolution at Lexington

in April 1775 carried a flag of red with a green pine tree emblem on a

field of white with them into battle at Bunker Hill in June 1775, in what

was to be the bloodiest battle of the entire war. Almost concurrently,

several small clashes took place in Kennebec, Falmouth and Portsmouth,

Maine between American lumberjacks and British authorities, all related

to the requisition or seizure of white pine masts which the British Royal

Navy so desperately needed. The American Revolution was in fact only a

piece of a much larger European conflict, whereby Britain found herself

pitted against every other European military power. France assisted the

American colonies, not out of any inherent friendship with these upstart

democratic states (France herself at that time was a monarchy, like England)

but simply to apply pressure on her political and military rival. The French

ships that blockaded Yorktown against the British Navy and sealed General

Cornwallis’ fate against the surrounding American forces all had white

pine masts courtesy of New England. It was one of the few moments in pre-industrial

history when the British Royal Navy was  outmaneuvered,

but it came at a critical time to effectively win American Independance.

The White Pine Tree has since appeared on the Massachusetts Coat of Arms

and Naval Flag; the first Seal of New Hampshire (1776); the Coat of Arms,

Seal and present Flag of Vermont; and the Coat of Arms, Seal, and all the

Flags, past and present, of Maine. Even today, after centuries of logging,

the Eastern White Pine is still seen practically everywhere one looks in

New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine, growing along highways and roads, and

covering massive tracts of wilderness.

outmaneuvered,

but it came at a critical time to effectively win American Independance.

The White Pine Tree has since appeared on the Massachusetts Coat of Arms

and Naval Flag; the first Seal of New Hampshire (1776); the Coat of Arms,

Seal and present Flag of Vermont; and the Coat of Arms, Seal, and all the

Flags, past and present, of Maine. Even today, after centuries of logging,

the Eastern White Pine is still seen practically everywhere one looks in

New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine, growing along highways and roads, and

covering massive tracts of wilderness.

however,

were the massive pines of the Inland Empire in Idaho and Montana, and of

the towering Douglas Fir forests in the Northwest.

however,

were the massive pines of the Inland Empire in Idaho and Montana, and of

the towering Douglas Fir forests in the Northwest.

The

reason Europeans could not get the coveted white pine to grow well in Europe

during the 18th and 19th centuries was because this native American pine

was no match for the blister rust of Asian origin that was endemic to Europe,

Cronartium

ribicola. All 5-needled pines from North America are highly susceptible

to this fungal pathogen that hardly blemishes native European pines. The

U.S. Forest Service, by planting German-grown seedlings by the million

from Maine to Minnesota, had unwittingly unleashed one of the most economically

and environmentally-damaging tree pathogen in US history. White Pine Blister

Rust gets its name because of the characteristic white aecia that develop

on the bark of infected trees which resemble grotesque blisters. These

aecia produce aeciospores that can travel 300 miles to infect members of

the Ribes genera (gooseberry), the required alternate host. The

fungus is not typically lethal to these small

The

reason Europeans could not get the coveted white pine to grow well in Europe

during the 18th and 19th centuries was because this native American pine

was no match for the blister rust of Asian origin that was endemic to Europe,

Cronartium

ribicola. All 5-needled pines from North America are highly susceptible

to this fungal pathogen that hardly blemishes native European pines. The

U.S. Forest Service, by planting German-grown seedlings by the million

from Maine to Minnesota, had unwittingly unleashed one of the most economically

and environmentally-damaging tree pathogen in US history. White Pine Blister

Rust gets its name because of the characteristic white aecia that develop

on the bark of infected trees which resemble grotesque blisters. These

aecia produce aeciospores that can travel 300 miles to infect members of

the Ribes genera (gooseberry), the required alternate host. The

fungus is not typically lethal to these small  shrubs.

Infection of gooseberry leaves occurs via the stomata on the undersides

of the leaves, and the fungal mycelium grows into the soft mesophyll cells

of the leaf and parasitizes them by injecting an absorptive filament, called

a haustorium, into the cytoplasm. Uredia, which are fruiting bodies, are

formed on the undersides of the gooseberry leaves during periods of cool,

moist weather within months of infection. Basidiospores are released and

carried on the wind 100-300 meters to any 5-needled pine. Basidiospores

cannot infect Ribes species.

shrubs.

Infection of gooseberry leaves occurs via the stomata on the undersides

of the leaves, and the fungal mycelium grows into the soft mesophyll cells

of the leaf and parasitizes them by injecting an absorptive filament, called

a haustorium, into the cytoplasm. Uredia, which are fruiting bodies, are

formed on the undersides of the gooseberry leaves during periods of cool,

moist weather within months of infection. Basidiospores are released and

carried on the wind 100-300 meters to any 5-needled pine. Basidiospores

cannot infect Ribes species.