Location:

East side of Lake Powell within the Navajo Nation on the Utah-Arizona border

Access: From

Page, AZ take Route 98 east ~50 miles, then head north on Navajo Mt Road

(Route 16). After ~20 miles, the road turns into a hard packed dirt road.

A fork in the road at around mile 30 is labeled by an old sign that says

Navajo Mt Trading Post. Take the left fork. In ~4 miles, take the right

fork just before a 60 ft sandstone knob on the right of the road called

Haystack Rock. You end up in a small clearing with a well that is called

War God Springs. This is as far as a low clearance vehicle can comfortably

go. About 1 mile up the dirt road to the NW lay the ruins of Rainbow Lodge

and the head of the south trail. The dirt road narrows and becomes the

trail, which is very well marked the entire way. There is also a north

trail from Navajo Mt Trading Post, but I don’t know much about it.

Maps: USGS

1:24K Quads: Chaiyahi Flat, Rainbow Bridge

Trail: Old

Rainbow Lodge to Rainbow Bridge is listed as 13 miles, with very dramatic

ascents and descents through rugged canyon country. The trail initially

climbs steadily up a root of Navajo Mt, splits and then rejoins a ½

mile later, then drops sharply down to 5920 feet in Horse Canyon, only

to ascend steeply through switchbacks up the next ridge to the north. From

there, the trail heads north uphill for a long time, and one rises up to

a maximum elevation of 6440 feet before topping Yabut Pass into Cliff Canyon.

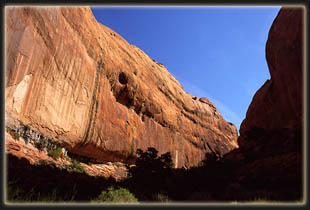

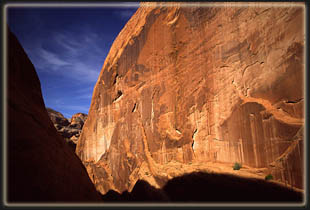

A long western-facing downhill trek takes you almost 2000 feet down to

the bed of Cliff Creek, where the sheer sandstone cliffs to the south rise

over 2000 feet above, providing the first shade of the hike. The trail

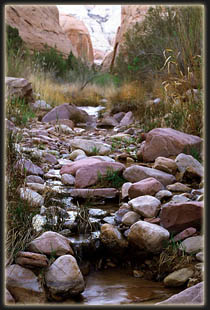

follows Cliff Creek to the NW for about 2.5 miles, and in April of 2003

numerous clear pools of water and sections of vigorously flowing water

were present. The elevation gradually decreases along the way to about

4200 feet before the trail takes an abrupt right turn at Redbud Pass and

climbs out of Cliff Canyon to the north and drops down into Redbud Creek.

Redbud Pass is a very narrow and steep route that rises perhaps 300-400

feet. Traveling from Cliff Canyon to Redbud Creek via the pass looks easier

than going the other direction, due to steep dropoffs on the northern side.

Less than a mile after meeting Redbud Creek, the trail intersects Bridge

Canyon, along with the northerly route from Navajo Mt Trading Post. From

there, the trail continues on only a couple more miles before entering

the monument. Rainbow Bridge is a very short stroll from the SE monument

boundary. Taking time to explore a couple of side canyons, and stopping

often for photographs, we made the hike from Rainbow Lodge to Rainbow Bridge

in two days, hiking about 5 hours/day.

Fees: Trip

permit $10 and camping fee of $2/night through the Navajo Nation; no fee

to enter the National Monument.

Friday April 18, 2003

The

alarm clock beeped at 6:30 and I got up and showered by way of a nozzle

head that practically required sitting down to get under. Dave was up letting

his dog out when I awoke. We had a quick breakfast of Caren’s breakfast

burritos and then loaded the car under a clear, blue Colorado sky that

provided a magnificent backdrop for the snow-shrouded heights of Pike’s

Peak. We left Colorado Springs behind at around 8:30, driving south down

I-25 through Pueblo in light traffic, while the poor tie-wearing commuters

sentenced to yet another work day drove north to the giant congestive hell

called Denver. I turned the car west at Walsenburg, then engaged the cruise

control on Hwy 160 for the long haul to Arizona. The mountain terrain,

dramatically accented by snowbanks on the relatively treeless slopes, almost

caused our trip to go no further than La Veta Pass where we both would’ve

been pleased to stop and backpack. We had lunch at Subway in Pagosa Springs,

but otherwise kept on the road. We encountered snow on Wolf Creek Pass,

and traffic was backed up due to an apparent tunnel construction project

that had cut the road down to a single lane. Fortunately, we arrived within

a minute or so of our lane getting to go through, so we really didn’t have

to wait at all. The skies were fairly grey and threatening from then on,

and we encountered some snow on the ground just east of Page, AZ. The

alarm clock beeped at 6:30 and I got up and showered by way of a nozzle

head that practically required sitting down to get under. Dave was up letting

his dog out when I awoke. We had a quick breakfast of Caren’s breakfast

burritos and then loaded the car under a clear, blue Colorado sky that

provided a magnificent backdrop for the snow-shrouded heights of Pike’s

Peak. We left Colorado Springs behind at around 8:30, driving south down

I-25 through Pueblo in light traffic, while the poor tie-wearing commuters

sentenced to yet another work day drove north to the giant congestive hell

called Denver. I turned the car west at Walsenburg, then engaged the cruise

control on Hwy 160 for the long haul to Arizona. The mountain terrain,

dramatically accented by snowbanks on the relatively treeless slopes, almost

caused our trip to go no further than La Veta Pass where we both would’ve

been pleased to stop and backpack. We had lunch at Subway in Pagosa Springs,

but otherwise kept on the road. We encountered snow on Wolf Creek Pass,

and traffic was backed up due to an apparent tunnel construction project

that had cut the road down to a single lane. Fortunately, we arrived within

a minute or so of our lane getting to go through, so we really didn’t have

to wait at all. The skies were fairly grey and threatening from then on,

and we encountered some snow on the ground just east of Page, AZ.

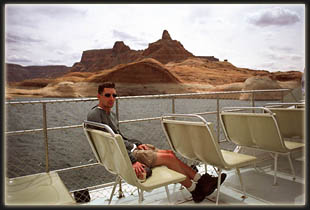

Our destination was Wahweap

Lodge and Marina, on the southern edge of Lake Powell. Outside of Page,

we approached Glen Canyon Dam. Some facts on the dam: 1,560 ft wide

at the crest, 710 ft above bedrock and 583 ft above the original Colorado

River bed. Concrete for the dam was poured around the clock for 3 straight

years, beginning in 1956. At full pool, the lake is 560 ft deep at the

dam (NPS, 2002). My first sight of the dam was a significant moment because

of all I had read about it, mostly from anti-dam critics like Edward Abbey,

David Brower and Katie Lee. I don’t pretend to be unbiased, but then again,

anyone who does is still just pretending. I don’t think anyone is unbiased

about anything. The images and  descriptions

of the wondrous beauty of Glen Canyon before the dam paint the immense

concrete and steel structure in a lurid light for me, and while I appreciate

the amazing utility of such a feature, I would have it not there if given

a choice. A trestle bridge spans the canyon just downstream of the dam.

The area is deliciously rugged and orange, with no plants whatsoever. The

only break in the sea of rock comes in the form of the hundreds of power

line towers and wires stretching every which way and off to the distance

like an occupying army. Nothing could look more out of place than

those steel towers. The canyon is very narrow, as good dam sites are apt

to be, and the walls are straight, tall and stained with a thousand streaks

of metal oxides. Looking at the water level above and below the dam gives

an appreciation for the immense holding capacity it has, especially when

one looks at the map and sees the Colorado River backed up over 100 miles

upstream, and into hundreds of side channels. Imagine the pressure on that

concrete. From what I have read, and heard, no other dam has generated

as much controversy as this one, and it was like confronting the villain

of a dream in living color. In my estimate, backed up by some obvious facts,

the dam has created an unnatural reservoir of cooler and clearer than normal

water in a dry area that benefits, of all animals, only non-native species

of fish, upsetting the entire ecosystem of the area, and flooding thousands

of square miles of fragile canyon riparian areas descriptions

of the wondrous beauty of Glen Canyon before the dam paint the immense

concrete and steel structure in a lurid light for me, and while I appreciate

the amazing utility of such a feature, I would have it not there if given

a choice. A trestle bridge spans the canyon just downstream of the dam.

The area is deliciously rugged and orange, with no plants whatsoever. The

only break in the sea of rock comes in the form of the hundreds of power

line towers and wires stretching every which way and off to the distance

like an occupying army. Nothing could look more out of place than

those steel towers. The canyon is very narrow, as good dam sites are apt

to be, and the walls are straight, tall and stained with a thousand streaks

of metal oxides. Looking at the water level above and below the dam gives

an appreciation for the immense holding capacity it has, especially when

one looks at the map and sees the Colorado River backed up over 100 miles

upstream, and into hundreds of side channels. Imagine the pressure on that

concrete. From what I have read, and heard, no other dam has generated

as much controversy as this one, and it was like confronting the villain

of a dream in living color. In my estimate, backed up by some obvious facts,

the dam has created an unnatural reservoir of cooler and clearer than normal

water in a dry area that benefits, of all animals, only non-native species

of fish, upsetting the entire ecosystem of the area, and flooding thousands

of square miles of fragile canyon riparian areas  that

took millennia to develop and stabilize. The recreational activities of

the lake are primarily motor-boat related, an activity which spews toxic

emissions, many times worse than those from automobiles, into the air and

results in thousands of gallons of spilled motor fuel and oil into the

water each year. Such boaters all too often discard of their used

comfort items, cups, bottles, cans, plates, forks, couches, etc., into

the lake, so that it has become the American southwest’s largest garbage

dump. The barren, rock buttes that jut out from the water are completely

lifeless, and the entire area seems sterile. The only touch of green I

saw came from invasive tamarisk patches. I overheard an old southern woman

sum it up best on the last day of our trip by asking her companion, in

typical southern ease, "Where’s all the wildlife?” Good question. Answer?

Native wildlife adapted to an intermittent river flow through sandy canyons,

not hundreds of feet of cold water surrounding stone pillars. There is

not much in the way of wildlife in the immediate area of the lake. It’s

all been drowned out. I am saddened by the destruction wrought by the dam,

but I am comforted by the thought that the Colorado River can play the

game longer than the dam, and finally, inevitably, crush the concrete into

dust, whereupon the river will flow as it always has, the white slime-stains

of the lake will be scoured from the rocks, the mountains of trash that

lay at the stinking lake bottom will wash into the ocean and the birds,

lizards, snakes, squirrels and insects will once again have a home in the

maze of sandstone canyons. that

took millennia to develop and stabilize. The recreational activities of

the lake are primarily motor-boat related, an activity which spews toxic

emissions, many times worse than those from automobiles, into the air and

results in thousands of gallons of spilled motor fuel and oil into the

water each year. Such boaters all too often discard of their used

comfort items, cups, bottles, cans, plates, forks, couches, etc., into

the lake, so that it has become the American southwest’s largest garbage

dump. The barren, rock buttes that jut out from the water are completely

lifeless, and the entire area seems sterile. The only touch of green I

saw came from invasive tamarisk patches. I overheard an old southern woman

sum it up best on the last day of our trip by asking her companion, in

typical southern ease, "Where’s all the wildlife?” Good question. Answer?

Native wildlife adapted to an intermittent river flow through sandy canyons,

not hundreds of feet of cold water surrounding stone pillars. There is

not much in the way of wildlife in the immediate area of the lake. It’s

all been drowned out. I am saddened by the destruction wrought by the dam,

but I am comforted by the thought that the Colorado River can play the

game longer than the dam, and finally, inevitably, crush the concrete into

dust, whereupon the river will flow as it always has, the white slime-stains

of the lake will be scoured from the rocks, the mountains of trash that

lay at the stinking lake bottom will wash into the ocean and the birds,

lizards, snakes, squirrels and insects will once again have a home in the

maze of sandstone canyons.

After

a spell examining the dam, we drove the car up the road and into the marina

area, paying the $10 Glen Canyon NRA entrance fee and receiving, in return,

a map of Lake Powell. Wahweap Marina straddles the Utah-Arizona border,

and it was here where we planned on staying the first night and picking

up the shuttle the following morning. Turned out that the tent site camping

area was closed, which was, of course, where we planned on camping, so

we had to go up to the RV site. We kept telling ourselves it was only for

a short night, and tried to ignore the gravel surface we had to set up

on, the RV generators switching on and off from all sides, barking dogs,

humming radios and television sets and dozens of security lights. We got

the site, then drove into Page for a quick, cheap Taco Bell dining experience.

While in town, I called the shuttle company and set up a pick up time and

place for the next morning. That set, we drove back to the campground and

went to sleep at dark. After

a spell examining the dam, we drove the car up the road and into the marina

area, paying the $10 Glen Canyon NRA entrance fee and receiving, in return,

a map of Lake Powell. Wahweap Marina straddles the Utah-Arizona border,

and it was here where we planned on staying the first night and picking

up the shuttle the following morning. Turned out that the tent site camping

area was closed, which was, of course, where we planned on camping, so

we had to go up to the RV site. We kept telling ourselves it was only for

a short night, and tried to ignore the gravel surface we had to set up

on, the RV generators switching on and off from all sides, barking dogs,

humming radios and television sets and dozens of security lights. We got

the site, then drove into Page for a quick, cheap Taco Bell dining experience.

While in town, I called the shuttle company and set up a pick up time and

place for the next morning. That set, we drove back to the campground and

went to sleep at dark.

Saturday, April 19

The

next morning we got up at 6, Arizona time (7 MDT) and quickly packed up

camp and left. We parked at the Wahweap Lodge and began methodically filling

up our packs with backcountry essentials for the next three days: moisture-wicking

socks, sun screen, water bottles, jerky, squeeze cheese, etc. Soon the

packs were full and we were ready to go. Our plan was to hire a shuttle

to ferry us by van to the old Rainbow Lodge on the south side of Navajo

Mt, hike for three days to and around Rainbow Bridge, camp anywhere we

liked, then take one of the twice-daily tour boats from Rainbow Bridge

back to Wahweap Lodge. When we returned to the marina, we would simply

hop in the car and drive off. All nice and neat. I confirmed our

return trip reservation with the boat tour desk at the marina, and we were

all set for the shuttle to pick us up at 7 AM. Seven came and went, and

I used Dave’s cell to call the driver at 10 after. He was in the wrong

place, or at least, not the place I was told to meet him at. He said

he’d be down in a few minutes, and we watched him drive up. We waved at

him, and he drove right past, so I ran after the van and flagged him down.

Dave and I both got nervous right from the start when the driver asked

us if we knew how to get to where we were going. He had no map in the van,

and professed to have never driven anywhere east of Page, which was where

we were going. The few directions I had downloaded from the amazing internet

alluded to unmarked dirt roads and four-wheel drive conditions, so the

fact that he had no idea where he was going, and had picked us up in a

2-wheel drive 15-passenger van, inspired no confidence whatsoever. Dave

and I exchanged sidelong glances of concern as the twitchy driver called

his boss and tried to figure things out. He finally felt comfortable with

where he was going, and we drove away at around 7:30. He had to stop in

Page for gas (another thing I thought was odd..why did he pick us up with

an empty tank?) and to clean the windshield. Finally, we were off. I tried

to quell my growing stress at having a driver who clearly had very little

idea how to get where he was going. The

next morning we got up at 6, Arizona time (7 MDT) and quickly packed up

camp and left. We parked at the Wahweap Lodge and began methodically filling

up our packs with backcountry essentials for the next three days: moisture-wicking

socks, sun screen, water bottles, jerky, squeeze cheese, etc. Soon the

packs were full and we were ready to go. Our plan was to hire a shuttle

to ferry us by van to the old Rainbow Lodge on the south side of Navajo

Mt, hike for three days to and around Rainbow Bridge, camp anywhere we

liked, then take one of the twice-daily tour boats from Rainbow Bridge

back to Wahweap Lodge. When we returned to the marina, we would simply

hop in the car and drive off. All nice and neat. I confirmed our

return trip reservation with the boat tour desk at the marina, and we were

all set for the shuttle to pick us up at 7 AM. Seven came and went, and

I used Dave’s cell to call the driver at 10 after. He was in the wrong

place, or at least, not the place I was told to meet him at. He said

he’d be down in a few minutes, and we watched him drive up. We waved at

him, and he drove right past, so I ran after the van and flagged him down.

Dave and I both got nervous right from the start when the driver asked

us if we knew how to get to where we were going. He had no map in the van,

and professed to have never driven anywhere east of Page, which was where

we were going. The few directions I had downloaded from the amazing internet

alluded to unmarked dirt roads and four-wheel drive conditions, so the

fact that he had no idea where he was going, and had picked us up in a

2-wheel drive 15-passenger van, inspired no confidence whatsoever. Dave

and I exchanged sidelong glances of concern as the twitchy driver called

his boss and tried to figure things out. He finally felt comfortable with

where he was going, and we drove away at around 7:30. He had to stop in

Page for gas (another thing I thought was odd..why did he pick us up with

an empty tank?) and to clean the windshield. Finally, we were off. I tried

to quell my growing stress at having a driver who clearly had very little

idea how to get where he was going.

The weather looked just plain

awful as we drove east, with low hanging clouds and fog all along the horizon.

I tried to keep optimistic about the chances for clearing. We drove north

on Navajo Mountain Road, listening to our driver fret about the road conditions

when it turned into a packed clay road after about 20 miles. My directions

advocated a left turn at the fork marked by the Navajo Mt School sign.

Unfortunately, there was no sign of that type anywhere, and we took a wrong

turn at a fork with a Navajo Mt Trading Post sign. By this time, our driver

had given up trying to follow his own instinct, and was simply asking us

where to go at every turn. We drove for awhile on that road, then decided

it was going the wrong way, and had him  turn

around. Stopped to ask a Navajo on horseback with three dogs directions

and he pointed us in the correct direction. Back on the right road, I told

him to turn right at the sandstone knob. He asked me what a sandstone knob

was. Clearly not a seasoned desert rat. I explained, and between Dave and

I, we managed to get the van to War God Springs, where the road gets very

sketchy. He started jerking his right arm into the air when the road turned

to 4-wheel drive, clearly getting nervous. I’m not kidding about the jerking

arm, it was the type of macro-nervous-tic I thought only existed in movies.

After half a mile, we had him stop and told him we’d walk from there on,

since the van was moving at a snail’s pace, and the violent jostling of

the long-bed vehicle was giving me a headache. He gratefully complied,

and we parted ways, paying him the full price for the shuttle despite his

getting

lost and not actually getting us to where we wanted to go. Down the trail

a bit, we stopped to adjust our packs and get things in order, glad to

be out of the van and on our own. A tremendous weight lifted as we

finally reached the part of the trip where we didn’t have to rely on shuttles,

campgrounds, gas stations or restaurants. Controlling one’s own destiny

is a very satisfying feeling that is hard to come by in this rush-hour

society. The GPS showed us to be but half a mile from the old Rainbow Lodge,

so we felt pretty good overall. turn

around. Stopped to ask a Navajo on horseback with three dogs directions

and he pointed us in the correct direction. Back on the right road, I told

him to turn right at the sandstone knob. He asked me what a sandstone knob

was. Clearly not a seasoned desert rat. I explained, and between Dave and

I, we managed to get the van to War God Springs, where the road gets very

sketchy. He started jerking his right arm into the air when the road turned

to 4-wheel drive, clearly getting nervous. I’m not kidding about the jerking

arm, it was the type of macro-nervous-tic I thought only existed in movies.

After half a mile, we had him stop and told him we’d walk from there on,

since the van was moving at a snail’s pace, and the violent jostling of

the long-bed vehicle was giving me a headache. He gratefully complied,

and we parted ways, paying him the full price for the shuttle despite his

getting

lost and not actually getting us to where we wanted to go. Down the trail

a bit, we stopped to adjust our packs and get things in order, glad to

be out of the van and on our own. A tremendous weight lifted as we

finally reached the part of the trip where we didn’t have to rely on shuttles,

campgrounds, gas stations or restaurants. Controlling one’s own destiny

is a very satisfying feeling that is hard to come by in this rush-hour

society. The GPS showed us to be but half a mile from the old Rainbow Lodge,

so we felt pretty good overall.

The sun was hidden behind

clouds to the east, but the weather had substantially improved since the

middle of the drive when it looked so bad. I started out with my sweatshirt

on, but pulled it off in about half a mile as the uphill trail warmed me

up quick. The dry desert air was intoxicating. We reached the ruins of

Rainbow Lodge, and noted a white pickup parked under the trees, apparently

belonging to two people whose footsteps we would see along the entire trail

but whose bodies remained hidden. Months ago, I was warned not to park

overnight at this spot in order to avoid automobile vandalism. Whether

that is a serious threat or not, I don’t know, but it was a factor in us

deciding to take a shuttle from Wahweap Lodge.

About

the time we left the old Rainbow Lodge, the sun rose above the clouds that

seemed to hover over Navajo Mt, and it really warmed up. We followed the

well-marked trail through sparse juniper and yucca, some of which were

sending up their annual bloom stalk. The trail split, and we took the lower

trail that switchbacked down into a wash, First Canyon, then turned west

and rose steadily up the next ridge. The silence of the still air was welcome,

and the methodical crunch of gravel underfoot soothed like a good massage.

Old horse droppings littered the trail. For most of this stretch, the view

to the south and west encompassed a vast expanse of canyon country, and

I kept stretching my head around to see it as we veered to the north. Clouds

still enveloped the summit of Navajo Mt, creating a stark contrast between

the snowy, cold peak and the warm, dry canyons. At the top of the

2nd ridge, the two forks of the trail joined again, just in time for a

steep and straight shot down into Horse Canyon, which runs almost directly

east-west. The trail down ran through comforting pockets of shade, although

the steepness of the dropoff literally caused me to get dizzy while looking

down. At the bottom of the draw, I wondered how in the world we would get

out since the opposing wall was so steep. Looks can be deceiving from below

a hill, Dave pointed out, and this one was no different, as we zig-zagged

up in a lot less time than I thought it would take. At the top, we shed

our packs and took a break. Amazingly, Dave’s cell phone was getting a

signal, so we called Matt, who almost made this trip with us, at home on

Long Island to say hello. I also called Andra and left a message on her

machine since she was still in southern California on her own little trip. About

the time we left the old Rainbow Lodge, the sun rose above the clouds that

seemed to hover over Navajo Mt, and it really warmed up. We followed the

well-marked trail through sparse juniper and yucca, some of which were

sending up their annual bloom stalk. The trail split, and we took the lower

trail that switchbacked down into a wash, First Canyon, then turned west

and rose steadily up the next ridge. The silence of the still air was welcome,

and the methodical crunch of gravel underfoot soothed like a good massage.

Old horse droppings littered the trail. For most of this stretch, the view

to the south and west encompassed a vast expanse of canyon country, and

I kept stretching my head around to see it as we veered to the north. Clouds

still enveloped the summit of Navajo Mt, creating a stark contrast between

the snowy, cold peak and the warm, dry canyons. At the top of the

2nd ridge, the two forks of the trail joined again, just in time for a

steep and straight shot down into Horse Canyon, which runs almost directly

east-west. The trail down ran through comforting pockets of shade, although

the steepness of the dropoff literally caused me to get dizzy while looking

down. At the bottom of the draw, I wondered how in the world we would get

out since the opposing wall was so steep. Looks can be deceiving from below

a hill, Dave pointed out, and this one was no different, as we zig-zagged

up in a lot less time than I thought it would take. At the top, we shed

our packs and took a break. Amazingly, Dave’s cell phone was getting a

signal, so we called Matt, who almost made this trip with us, at home on

Long Island to say hello. I also called Andra and left a message on her

machine since she was still in southern California on her own little trip.

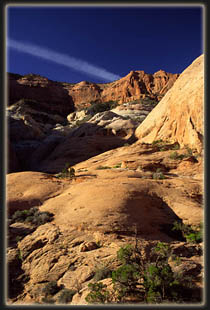

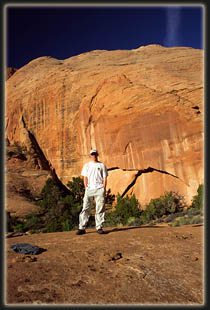

Continuing on, the trail

just went higher, though I expected it to start descending. Up and up we

went, with an increasingly breathtaking view opening up to the west all

the time, and the crack of Dome Canyon yawning over a thousand feet below.

Beyond that, a sea of sandstone boiled in curves, twists and fingers, completely

obscuring any routes or passes through this land. Miles away on the horizon,

massive cliffs of the Kaiparowits Plateau rose up several thousand feet

above. I spent lots of time stopping all along the trail, and while in

subsequent camps, to take photographs. Since I had my tripod, a fully manual

camera, two lenses and two filters, setup times often lasted several minutes.

I’m sure Dave got bored waiting on me, but I bribed him off by promising

to send him a CD with all the slide scans from the trip in a month or two,

so all should be well. He brought his small APS camera, but forgot to bring

film, therefore, my photographs should be of interest to him. The sky cleared

above Navajo Mt, but we were too close to see the actual summit. Before

long, we approached Yabut Pass over the massive rock wall that separates

Dome Canyon from Cliff Canyon, and stopped in the shadow cast by the wall

on the Cliff Canyon side. There we ate an impromptu lunch of cheese, crackers

and jerky, washed down with Fruit Punch Gatorade. Fine dining in canyon

country. An inscription on the wall said something about suffering. We

hoped it wasn’t a prediction of things to come. The drop down into Cliff

Canyon was a long, steep drop of almost 2000 feet that brought blisters

to my feet and shakes to my thighs. Lizards darted to and fro in the rocks

on the sides of the trail, appearing and disappearing like Halloween tricksters.

I scratched my legs on the abundant bitterbrush. We stopped in the cool

shade of the canyon bottom for another break, and I took some ibuprofen

for my headache that was causing blood to pound in my skull with each step.

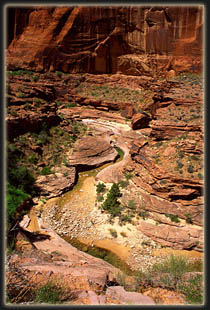

We looked around in the creek

for water, and found none, making us a little nervous. I had brought a

gallon, and so had Dave, but that wouldn’t last us two days so we had to

find water somewhere. We continued on, mostly in the shade, along a gentle,

sand trail that had few obstacles. From that point on, the tough hiking

was 95% done with, and we reveled in the soft, flat trail by Cliff Creek.

It had taken us almost 4 hours to get to Cliff Creek, so we basically decided

to plop down at the  first

good spot we found. There was a lot more vegetation in the canyon

than I had expected, thinking it would be something like the Needles District

at Canyonlands. It was not. Willow and juniper provided a relatively dense

canopy in spots, while the ground was covered with prickly pear, blooming

red penstemon, sharp yucca and soft clumps of new Indian Rice Grass and

Cheatgrass. A few puddles came into view, and we grew hopeful. We passed

them by, and soon there were regular pools of water, some looking more

tasty than others. The first spot we checked would have been perfect –

a nice flat sandy ledge above the creek with water nearby – had it not

been for the incredibly robust prickly pear population. We found a few

small flat spots that were cactus-free, but neither of us was thrilled

with the spot. We left our gear there and explored downstream and found

a great spot that was open, sandy, cactus-free and near water. So, back

up to get our stuff, down canyon once again about 100 yards. There we relaxed,

pulled off our boots and sat in the shade sipping Gatorade. I should try

to describe this campsite, but a picture will do better. It was all

fine and well, but soon we became restless and decided to go exploring. first

good spot we found. There was a lot more vegetation in the canyon

than I had expected, thinking it would be something like the Needles District

at Canyonlands. It was not. Willow and juniper provided a relatively dense

canopy in spots, while the ground was covered with prickly pear, blooming

red penstemon, sharp yucca and soft clumps of new Indian Rice Grass and

Cheatgrass. A few puddles came into view, and we grew hopeful. We passed

them by, and soon there were regular pools of water, some looking more

tasty than others. The first spot we checked would have been perfect –

a nice flat sandy ledge above the creek with water nearby – had it not

been for the incredibly robust prickly pear population. We found a few

small flat spots that were cactus-free, but neither of us was thrilled

with the spot. We left our gear there and explored downstream and found

a great spot that was open, sandy, cactus-free and near water. So, back

up to get our stuff, down canyon once again about 100 yards. There we relaxed,

pulled off our boots and sat in the shade sipping Gatorade. I should try

to describe this campsite, but a picture will do better. It was all

fine and well, but soon we became restless and decided to go exploring.

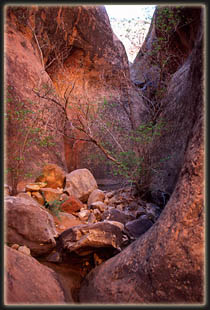

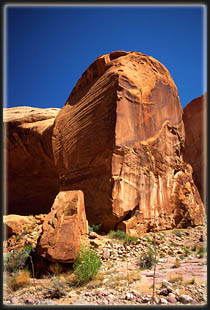

Because of the winding nature

of the canyon, one couldn’t see down- or up-canyon very far at all. Numerous

fins overlapped to block the view. Between each of these fins was a side

canyon just waiting to be explored. We happened to have a deep looking

side canyon just to the north of our camp, so we walked up there right

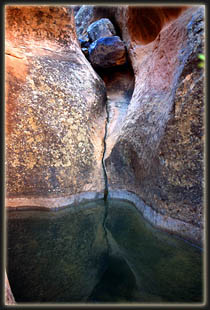

away. First we crossed a gentle slope of  grass,

yucca and juniper that led out of the warm sunlight into the cool shade,

then we hit a solid sandstone slope and walked quietly uphill. A sandy

strip with grass and redbud lay between two opposing planes of rock. The

purple blossoms of the redbud sweetened the air. The draw grew thinner,

and steeper, and soon it was a matter of strict concentration to avoid

slipping all the way to the bottom of the giant V we were now traversing.

I appreciated the grip of my lug-soled boots. The walls stretched a couple

hundred feet above, blocking out almost all light. As the walls drew closer,

the dark shade cooled the air even more. Along one wall, a long, horizontal

seep had created a profuse hanging garden of maiden hair fern, moss, and

a few other plants that I’d never seen before, perhaps being too rare to

put in field guides. The walls became steep enough to necessitate the use

of both hands, so I had to cache my tripod and take along just the camera

on my back. With feet on one wall, and hands pressing against the other,

we managed to make grass,

yucca and juniper that led out of the warm sunlight into the cool shade,

then we hit a solid sandstone slope and walked quietly uphill. A sandy

strip with grass and redbud lay between two opposing planes of rock. The

purple blossoms of the redbud sweetened the air. The draw grew thinner,

and steeper, and soon it was a matter of strict concentration to avoid

slipping all the way to the bottom of the giant V we were now traversing.

I appreciated the grip of my lug-soled boots. The walls stretched a couple

hundred feet above, blocking out almost all light. As the walls drew closer,

the dark shade cooled the air even more. Along one wall, a long, horizontal

seep had created a profuse hanging garden of maiden hair fern, moss, and

a few other plants that I’d never seen before, perhaps being too rare to

put in field guides. The walls became steep enough to necessitate the use

of both hands, so I had to cache my tripod and take along just the camera

on my back. With feet on one wall, and hands pressing against the other,

we managed to make  it

past a particularly steep spot that opened up beyond into a less steep

area that was quiet, dark and very lush with riparian species living off

the slow seeping water pressing through the crack in the wall. There

the path ended, as the far side was way too steep for anybody to manage.

The box end foiled us, and we turned back, but not disappointed by any

stretch. In fact, this little side canyon exploration was my personal favorite

moment of the trip. From the high point on our way out we could look across

Cliff Creek to the other promising chutes and draws and see that they led

nowhere in a big hurry. Dave had opted out of his hiking boots for this

little trip, but paid for that choice by stabbing his toe on a yucca leaf

that quickly embedded itself under the skin, and required minor surgery

with a needle to remove back at camp. We walked down canyon to the next

draw and began climbing up toward it, but before we got very far, we could

see it was too steep to try, and we went back to camp. it

past a particularly steep spot that opened up beyond into a less steep

area that was quiet, dark and very lush with riparian species living off

the slow seeping water pressing through the crack in the wall. There

the path ended, as the far side was way too steep for anybody to manage.

The box end foiled us, and we turned back, but not disappointed by any

stretch. In fact, this little side canyon exploration was my personal favorite

moment of the trip. From the high point on our way out we could look across

Cliff Creek to the other promising chutes and draws and see that they led

nowhere in a big hurry. Dave had opted out of his hiking boots for this

little trip, but paid for that choice by stabbing his toe on a yucca leaf

that quickly embedded itself under the skin, and required minor surgery

with a needle to remove back at camp. We walked down canyon to the next

draw and began climbing up toward it, but before we got very far, we could

see it was too steep to try, and we went back to camp.

We filtered water from one

of the large, still pools in the creek bed, then cooked dinner of 3 cheese

rotini and complemented that with jerky. Nothing but the best. Dave ceremoniously

devoured his Twix bar, carefully preserved for just this moment. I  decided

to save mine for the following night. We arranged our sleeping pads

out in the open on a flat sand patch, hidden from the trail by a series

of very large black rocks. I strolled around looking at plants and rocks,

and while jumping from a high rock to the sand below rammed my knee into

a yucca plant that immediately drew blood which soaked through the thin

quick-drying fabric of my pants. Those darn things are pretty vicious.

I noted that many yucca along the way had been browsed and I found it hard

to believe that any animal could find such tough fibrous leaves palatable. decided

to save mine for the following night. We arranged our sleeping pads

out in the open on a flat sand patch, hidden from the trail by a series

of very large black rocks. I strolled around looking at plants and rocks,

and while jumping from a high rock to the sand below rammed my knee into

a yucca plant that immediately drew blood which soaked through the thin

quick-drying fabric of my pants. Those darn things are pretty vicious.

I noted that many yucca along the way had been browsed and I found it hard

to believe that any animal could find such tough fibrous leaves palatable.

As the sun set, the shadows

in the canyon became cool, and by dark it was fairly chilly. The stars

came out in a crystal clear sky, and I attempted evening star shots as

Dave drifted off to sleep. We were talking most of the evening, and then

suddenly, Dave stopped answering. I shut up and took more pictures. Frogs

croaked like mechanical sheep down the canyon, suggesting more abundant

water in that direction. Despite the pools of water, insects were pretty

scarce. I took a few shots around 9 PM, but felt too tired to stay up any

later bothering with that. I laid the tripod down on the ground, and put

my camera away. An owl made his presence known somewhere nearby. I fell

asleep very quickly, waking up in the middle when Dave, who was sleeping

about 8 feet away, poked me with my camera tripod trying to get me to stop

snoring.

Sunday, April 20

It was a chilly night, and

I slept with my head buried inside the bag. Several times I poked my head

out of the bag to watch the stars, in their unpolluted clarity, for a few

seconds before going back to sleep. As morning approached, birds began  singing,

and the bright light of dawn hurt my eyes. When I finally got up around

6:30, the outside of my bag was soaked with dew. The entire canyon was

in shadow, but I could see a single sliver of golden sandstone far off

down the canyon where the sun was shining. The sky was cloudless. In the

chilly morning air, I got dressed as Dave woke up. Due to the wet bags,

we decided to wait until the sun was in camp to dry things out before leaving,

contrary to the original plan of getting to the bridge as soon as we could.

Therefore, I walked down the canyon to see if there were any good morning

photographic opportunities. Very shortly on my walk downstream I came upon

running water, coming from some unseen spring in one of the numerous side

chutes winding up and out of sight on both sides of the singing,

and the bright light of dawn hurt my eyes. When I finally got up around

6:30, the outside of my bag was soaked with dew. The entire canyon was

in shadow, but I could see a single sliver of golden sandstone far off

down the canyon where the sun was shining. The sky was cloudless. In the

chilly morning air, I got dressed as Dave woke up. Due to the wet bags,

we decided to wait until the sun was in camp to dry things out before leaving,

contrary to the original plan of getting to the bridge as soon as we could.

Therefore, I walked down the canyon to see if there were any good morning

photographic opportunities. Very shortly on my walk downstream I came upon

running water, coming from some unseen spring in one of the numerous side

chutes winding up and out of sight on both sides of the  creek.

This has been described as a permanent spring called First Water by numerous

authors, and has a couple of well-used campsites nearby. The running water

provided suitable habitat for cat tails, Equisetum and tall reedy grasses,

in addition to redbuds, box elders and willows. Some of the healthiest

Ephedra plants I’ve ever seen reside here. In the jungle-like canyon bottom,

I bulled my way down the narrow, overgrown trail, where off to the left

sat a wooden outhouse, seeming very out of place in this completely remote

area, but confirming that this area has historically been an overnight

stop for hikers and packers. An occasional mosquito buzzed in my

face, but the bugs were surprisingly and pleasantly few. A little further

down I found a side canyon that looked shallow enough for my boots to grip,

and walked up. Halfway, the pitch steepened, and I cached my camera on

a ledge so I could use both my hands. I didn’t go more than 50 or 60 feet

up before I reached a dome that hung out over the creek. Hoping I could

see camp from there, I got to the top, but the view up canyon was blocked

by an intervening fin. I slowly scooted down and returned to camp. creek.

This has been described as a permanent spring called First Water by numerous

authors, and has a couple of well-used campsites nearby. The running water

provided suitable habitat for cat tails, Equisetum and tall reedy grasses,

in addition to redbuds, box elders and willows. Some of the healthiest

Ephedra plants I’ve ever seen reside here. In the jungle-like canyon bottom,

I bulled my way down the narrow, overgrown trail, where off to the left

sat a wooden outhouse, seeming very out of place in this completely remote

area, but confirming that this area has historically been an overnight

stop for hikers and packers. An occasional mosquito buzzed in my

face, but the bugs were surprisingly and pleasantly few. A little further

down I found a side canyon that looked shallow enough for my boots to grip,

and walked up. Halfway, the pitch steepened, and I cached my camera on

a ledge so I could use both my hands. I didn’t go more than 50 or 60 feet

up before I reached a dome that hung out over the creek. Hoping I could

see camp from there, I got to the top, but the view up canyon was blocked

by an intervening fin. I slowly scooted down and returned to camp.

Upon my return, we discussed

the timing of the day, and decided that since the sun had not yet even

touched the top of the canyon walls, a considerable delay would be inevitable

should we continue to wait for the sun to dry things out prior to leaving.

We decided to leave, and dry bags out later. We quickly packed up camp

and took off. As we approached the side chute on the right of the canyon

that I had earlier ascended, I pointed out a much more robust side canyon

on the opposite  wall

that looked worth exploring. Dave agreed. We shed our packs right next

to the trail and took off up the steep, grassy slope that led up like a

stairway between two unscalable rock walls. The shadow-cloaked slope was

very steep, and we dodged the yucca and cactus on our separate routes up.

Giant angular choke stones, calved from the towering walls above perhaps

before men walked on two legs, provided soil anchors that kept the entire

canyon from being a smooth rock wash. Sweet-smelling redbud provided the

most difficult obstacle to getting up as I bent and wormed my way under

their low-hanging limbs. After several hundred feet, the canyon forked,

and we took the smaller, narrower left fork into a short box canyon that

ended in an abrupt wall. The entrance to this canyon was no more than 6

feet wide, but opened up inside to about 15 feet. An overhanging spout,

stained by metal oxides from centuries of intermittent water flow, hung

directly over a perfectly smooth sandstone bowl filled with cold, dark

water. The round pool was about 10 feet in diameter, hidden like a treasure

in this indistinct and small cove. A side canyon of a side canyon of a

side wall

that looked worth exploring. Dave agreed. We shed our packs right next

to the trail and took off up the steep, grassy slope that led up like a

stairway between two unscalable rock walls. The shadow-cloaked slope was

very steep, and we dodged the yucca and cactus on our separate routes up.

Giant angular choke stones, calved from the towering walls above perhaps

before men walked on two legs, provided soil anchors that kept the entire

canyon from being a smooth rock wash. Sweet-smelling redbud provided the

most difficult obstacle to getting up as I bent and wormed my way under

their low-hanging limbs. After several hundred feet, the canyon forked,

and we took the smaller, narrower left fork into a short box canyon that

ended in an abrupt wall. The entrance to this canyon was no more than 6

feet wide, but opened up inside to about 15 feet. An overhanging spout,

stained by metal oxides from centuries of intermittent water flow, hung

directly over a perfectly smooth sandstone bowl filled with cold, dark

water. The round pool was about 10 feet in diameter, hidden like a treasure

in this indistinct and small cove. A side canyon of a side canyon of a

side  canyon

of Glen Canyon. We backed out of the narrow opening, and continued on up

the main drainage. We reached a spot after several hundred more feet where

the slope converged with the left wall so that we could walk out on top

of a huge sandstone dome. Far from being smooth, the surface of this dome

was covered with tiny 1mm spikes that pricked my ass as I sat down.

From the vantage point, we could look down and see our starting point by

the Cliff Creek, as well as ascertain that if time allowed, we could continue

on up the side canyon indefinitely, perhaps all the way to the top of the

towering cliffs at the top of the horizon. Time, unfortunately, did not

allow such an excursion. Perhaps another day. With so many places to see

in this world, and only 60 walking years to see it in (if one is lucky),

I think the chances that I will go back to visit that particular side canyon

in that remote corner of Lake Powell are slim to canyon

of Glen Canyon. We backed out of the narrow opening, and continued on up

the main drainage. We reached a spot after several hundred more feet where

the slope converged with the left wall so that we could walk out on top

of a huge sandstone dome. Far from being smooth, the surface of this dome

was covered with tiny 1mm spikes that pricked my ass as I sat down.

From the vantage point, we could look down and see our starting point by

the Cliff Creek, as well as ascertain that if time allowed, we could continue

on up the side canyon indefinitely, perhaps all the way to the top of the

towering cliffs at the top of the horizon. Time, unfortunately, did not

allow such an excursion. Perhaps another day. With so many places to see

in this world, and only 60 walking years to see it in (if one is lucky),

I think the chances that I will go back to visit that particular side canyon

in that remote corner of Lake Powell are slim to  none.

Such a sentiment compels me to take as many photographs and notes as I

can on each place I visit, since I know I will visit few of them a second

time. So many canyons. So little time. none.

Such a sentiment compels me to take as many photographs and notes as I

can on each place I visit, since I know I will visit few of them a second

time. So many canyons. So little time.

The trip back down the side

canyon took very little time, and before we could turn around, we were

back at the creek, chugging water and having a snack. After hiking

another ½ mile or so, we stopped again to filter water from Cliff

Creek before leaving it to cross Redbud Pass. The water in Cliff Creek

was tasty, and plentiful, but we didn’t know what to expect in Bridge Creek.

We also took the time to apply sun screen. Dave, who comes from upstate

NY, and hadn’t seen the sun in 10 months, burned his legs and elbows by

not applying sun screen to those spots the previous day. I escaped such

a fate, but had terrible blisters on my feet which he seemed immune to.

We skinned an orange and downed it, then continued on  under

a perfect, and I mean perfect, blue desert sky. I don’t know if it’s the

contrast between the orange rock and blue sky, or whether the dry air makes

colors more vibrant, but I’ve just never seen such a blue sky anywhere

but in canyon country. under

a perfect, and I mean perfect, blue desert sky. I don’t know if it’s the

contrast between the orange rock and blue sky, or whether the dry air makes

colors more vibrant, but I’ve just never seen such a blue sky anywhere

but in canyon country.

Near Redbud Pass, we noted

an old wooden shelter shaped like a teepee. Perhaps part of the Rainbow

Lodge accommodations from the 1950’s? Who knows? There are no informational

placards out here, and it is good to have some mysteries left unsolved.

As we turned right into Redbud Pass, Cliff Canyon continued on and out

of sight around a right bend, quietly beckoning us to explore its lonely

depths. Again, we had no time to do so. Redbud Pass still confounds me

with its steepness. Looking at a highly detailed 7.5’ quad map, I can’t

count more than 2 contour lines (at 40 feet each) that must be crossed

to reach the top of Redbud Pass, yet the elevation gain is several hundred

feet, at least. Probably the most dramatic narrow-canyon section of the

entire route is that through Redbud Pass, where two massive, near-vertical

walls frame a trail in places just wide enough to lead a horse through.

The steepness is compounded by the loose sand trail, which makes it hard

to get a good footing. The pass is aptly named, as hundreds of redbuds

line the thin corridor. The sweet  smell

of their tiny purple blossoms freshened the air beyond description. Other

flowers lent color to the pass. Indian paintbrush bloomed red in profusion,

and I saw a single claretcup cactus in full bloom, its blood-red petals

standing out like neon against the shadows of the juniper trees.

The sandy flats where the soil was deeper were covered with prairie wild

onions, their numerous blooms appearing almost like purple and white striped

ribbon candy, and there was no mistaking their pungent aroma. One could

tell the trail was not well traveled since grass and lupine grew right

in the middle of the path. smell

of their tiny purple blossoms freshened the air beyond description. Other

flowers lent color to the pass. Indian paintbrush bloomed red in profusion,

and I saw a single claretcup cactus in full bloom, its blood-red petals

standing out like neon against the shadows of the juniper trees.

The sandy flats where the soil was deeper were covered with prairie wild

onions, their numerous blooms appearing almost like purple and white striped

ribbon candy, and there was no mistaking their pungent aroma. One could

tell the trail was not well traveled since grass and lupine grew right

in the middle of the path.

By the top of Redbud Pass,

marked by a wooden sign held up by a rock pile, my feet were in agony from

blisters that had developed and intensified on my toes and the ball of

each foot. I removed shoes to inspect the damage, found several  blisters

already ruptured, and decided there was little I could do but try to ignore

the stinging. The way down Redbud Pass, toward Redbud Creek, was much more

rugged than the way up. I had read that someone spent a lot of time trying

to improve the trail with dynamite and shovel work back in the 1920’s to

make it passable to pack animals. If at one time horses could descend this

route, they would surely not be able to now. Several 6-9 foot drop-offs

required cautious descents with all four limbs. We began to appreciate

even more the one-way design of our trip. We slowly picked our way down

a boulder field between the two rock walls, and I wondered if we had somehow

lost the trail. No other conceivable route existed, however, so we continued

down at a snail’s pace, cautiously testing each step to make sure each

rock wouldn’t bound down the hill with one of us on it. As the terrain

leveled, the distinct outline of the trail returned, and we were able to

once again walk in comfort. The trail remained a track through a crack

in the rock, almost like a tunnel, and truly a tunnel as it wound between

a vertical rock wall on the left, and vigorous white oak thickets on the

right that covered the trail from above. Flecks of sunlight scattered on

the soft sand of the trail, and the cool shadows felt very refreshing.

The temperature was rising as we were descending towards the river, or

what is now the lake, and we were both sure to keep drinking plenty of

fluids to fend off any uncomfortable side effects of dehydration. blisters

already ruptured, and decided there was little I could do but try to ignore

the stinging. The way down Redbud Pass, toward Redbud Creek, was much more

rugged than the way up. I had read that someone spent a lot of time trying

to improve the trail with dynamite and shovel work back in the 1920’s to

make it passable to pack animals. If at one time horses could descend this

route, they would surely not be able to now. Several 6-9 foot drop-offs

required cautious descents with all four limbs. We began to appreciate

even more the one-way design of our trip. We slowly picked our way down

a boulder field between the two rock walls, and I wondered if we had somehow

lost the trail. No other conceivable route existed, however, so we continued

down at a snail’s pace, cautiously testing each step to make sure each

rock wouldn’t bound down the hill with one of us on it. As the terrain

leveled, the distinct outline of the trail returned, and we were able to

once again walk in comfort. The trail remained a track through a crack

in the rock, almost like a tunnel, and truly a tunnel as it wound between

a vertical rock wall on the left, and vigorous white oak thickets on the

right that covered the trail from above. Flecks of sunlight scattered on

the soft sand of the trail, and the cool shadows felt very refreshing.

The temperature was rising as we were descending towards the river, or

what is now the lake, and we were both sure to keep drinking plenty of

fluids to fend off any uncomfortable side effects of dehydration.

Redbud

Pass drops hikers into Redbud Creek, which has a spectacular canyon of

its own. I don’t recall looking up-canyon, but that probably would be a

great place to go explore. Once again, if I ever come back…. Hardly a stone’s

throw from where the trail intersects Redbud Creek, Redbud Creek intersects

Bridge Creek in Bridge Canyon, and the trail from Navajo Mt Trading Post,

which was the original trail to Rainbow Bridge established in the teens

after the white-man discovery of Rainbow Bridge in 1909. This was

the real sign that we were getting very close. Bridge Canyon was much wider

than Cliff Canyon, and seemed to have taller walls, although I think this

may just be a consequence of having fewer side canyons and corresponding

ridges. The walls were mostly sheer and vertical, with numerous giant overhangs

that sheltered inviting campsites. Bridge Creek ran with more volume,

although we found out later the taste of the water was definitely inferior

to Cliff Creek, for whatever reason. Redbud

Pass drops hikers into Redbud Creek, which has a spectacular canyon of

its own. I don’t recall looking up-canyon, but that probably would be a

great place to go explore. Once again, if I ever come back…. Hardly a stone’s

throw from where the trail intersects Redbud Creek, Redbud Creek intersects

Bridge Creek in Bridge Canyon, and the trail from Navajo Mt Trading Post,

which was the original trail to Rainbow Bridge established in the teens

after the white-man discovery of Rainbow Bridge in 1909. This was

the real sign that we were getting very close. Bridge Canyon was much wider

than Cliff Canyon, and seemed to have taller walls, although I think this

may just be a consequence of having fewer side canyons and corresponding

ridges. The walls were mostly sheer and vertical, with numerous giant overhangs

that sheltered inviting campsites. Bridge Creek ran with more volume,

although we found out later the taste of the water was definitely inferior

to Cliff Creek, for whatever reason.

The

temperature approached the mid seventies, and we stopped for a break at

a bend in the creek. I ate some cheese and crackers and aired out my boots.

The down-canyon breeze in the shade almost made it feel cold, so both Dave

and I oscillated between sitting in the warm sun, and the cool shade. I

pulled out a map and pondered the possibilities. Rainbow Bridge lies in

the middle of its own small, square National Monument covering 160 acres,

or about 2/3 square mile. No camping is allowed within the monument, but

since that was what we came to see, we wanted to camp as close to it as

possible while staying on Reservation land. The

temperature approached the mid seventies, and we stopped for a break at

a bend in the creek. I ate some cheese and crackers and aired out my boots.

The down-canyon breeze in the shade almost made it feel cold, so both Dave

and I oscillated between sitting in the warm sun, and the cool shade. I

pulled out a map and pondered the possibilities. Rainbow Bridge lies in

the middle of its own small, square National Monument covering 160 acres,

or about 2/3 square mile. No camping is allowed within the monument, but

since that was what we came to see, we wanted to camp as close to it as

possible while staying on Reservation land.

Conversation turned to our

plans for camping on the road after the boat picked us up and dropped us

off at Wahweap Lodge the next afternoon. Since camping along the road is

forbidden inside the reservation, and since it takes at least 2 hours to

drive to Mexican Hat, the first town outside of the reservation on the

way back east, we decided that the afternoon boat would come too late for

us to do anything but camp once again at Wahwap Marina. Neither of us wanted

to do that again. Therefore, we decided that seeing the bridge for the

next 12 hours was enough, and we would attempt to take the morning  tour

boat back to Wahweap, arrive there by 3 and hopefully get to open BLM land

(and free camping) north of Mexican Hat by dark. tour

boat back to Wahweap, arrive there by 3 and hopefully get to open BLM land

(and free camping) north of Mexican Hat by dark.

We put our packs back on

and continued, knowing we were close, and keeping our eyes open for possible

campsites. Several appeared, and we made mental notes. Since it was very

tough to say where the boundary was, the plan evolved into “hike to the

boundary, then turn around and camp in the first good spot”. We followed

the trail until it started to climb steeply away from the creek. Figuring

we were close to the bridge, we decided that the trail must eventually

meet the creek, and followed a well-defined trail down to the creek and

followed it. The creek bed was solid rock for a spell, and a spout fell

into a deep pool of greenish water that was at least 6 feet deep and ran

in a channel for about 30 feet, being about 10 feet wide. If it were a

hot summer day I would’ve hopped right in, but the water would’ve been

far too cold for that while we were there. The creek bed drew narrower,

and the walls steeper, until we could go no further, and realized the futility

of our effort to hug the creek. We figured the trail was up above somewhere,

and that if we climbed far enough, we’d reach it. It is amazing how fast

we descended so far below the trail, for while we were walking downhill,

it was leading steeply uphill. The result was that we had to climb over

a hundred feet of treacherous 60-70 degree slope to get back on the trail.

While resting at the top after the arduous climb up, Dave studied the map,

and determined that we would not be able to get down to the creek until

well  inside

the monument, and since camping hinged on good water, we turned back to

the previously sited spot that had ample water and good tent sites. We

set down our packs for the day at 12, about 5 hours after starting out

from camp that morning. inside

the monument, and since camping hinged on good water, we turned back to

the previously sited spot that had ample water and good tent sites. We

set down our packs for the day at 12, about 5 hours after starting out

from camp that morning.

This campsite was marvelous.

Giant planks of flat, though rippled, rock (and I don’t think it was sandstone)

formed a multi-leveled platform that overlooked a large, waist-deep pool

of crystal clear water that had water rushing both in and out, filling

and emptying simultaneously, in perpetuity. A sandy beach provided a perfect

tent site, after Dave excavated a giant rock from the middle, while the

flat rocks provided perfect sitting and cooking areas. The rocks above

the pool provided a perfect seat to sit and soak tired, hot feet in the

cold water, which we did as soon as we arrived. We pulled out our wet sleeping

bags and dried them in minutes under the mid day sun. I doctored my blisters

by lancing them and applying bandages while Dave tended to his severely

burned legs. Within an hour of staking our claim, we put a couple of water

bottles in a bag and took off up the trail (not detouring by the creek

this time). We passed through a dilapidated barbed-wire gate, then followed

a flat trail around a deep and thin wash. At the source of this wash lay

the old tourist camp, Echo Camp,  complete

with rusting bed frames and cottage foundations. It was all fenced off,

perhaps for archeological and historical reasons. It didn’t look like an

inviting place to explore anyway so we weren’t disappointed to be herded

along by the obstacles. I was much happier with our open camp than I would’ve

been in this overgrown alcove. complete

with rusting bed frames and cottage foundations. It was all fenced off,

perhaps for archeological and historical reasons. It didn’t look like an

inviting place to explore anyway so we weren’t disappointed to be herded

along by the obstacles. I was much happier with our open camp than I would’ve

been in this overgrown alcove.

The trail stayed pretty flat

as it side-hilled around the slopes and gulleys, weaving left and right

between side-rails of rocks, laboriously stacked along both sides. The

open, flat areas to the right of the trail harbored an abundance of plant

life. Delicate white evening primrose and fading Utah daisies were the

most abundant, but individual desert trumpets and scattered blooming fishhook

cactus provided more color. Once again, I was impressed by the diversity

and abundance of plant life in the thin strip of green along the canyon

bottom. While the trail stayed more or less level, the creek bed, fell

more sharply away, and soon was clearly inaccessible without climbing gear.

I was walking in front on the trail, and Dave caught first sight of part

of Rainbow Bridge off down the canyon and pointed it out. It was much closer

to the monument boundary  than

I had expected, but there it was, a tremendous arch that appeared tiny

against the enormous canyon walls and buttes rising around it. than

I had expected, but there it was, a tremendous arch that appeared tiny

against the enormous canyon walls and buttes rising around it.

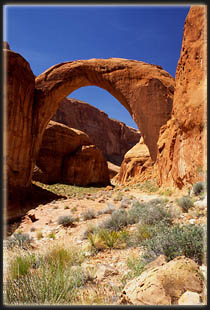

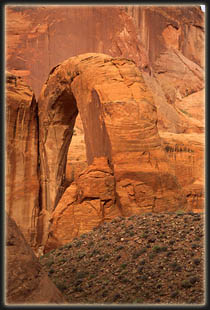

In the American Southwest,

you will find a concentration of sandstone formations that are called arches,

windows or bridges. The designation depends on their method of formation.

Millions of words have been written about the geology of the American Southwest,

so I won’t delve into that too much here. Put simply, water erodes the

6 ancient sandstone layers differentially, forming winding waterways that

get deeper with time. In between each waterway segment there develops,

by default, an increasingly tall ridge that gets narrower as the water

cuts a deeper draw. The outer layer of a sandstone fin is often the

strongest, and the inner section of the fin sometimes simply drops away,

creating an arch. Sometimes, quirks of wind dynamics cause a hole to be

sand-blasted into a fin, creating a window. Other times, a creek

will simply wear away at a spot on the base of a fin until it breaks through,

creating a bridge (since it spans water). In all cases, an initially small

opening is then worn wider and wider with time and smooths out to form

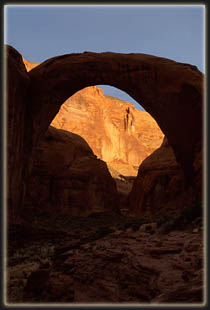

delicate and graceful shapes and curves. Rainbow Bridge spans Bridge Creek,

and is the largest natural bridge in the world, with a maximum height from

creek bed to the highest point of the arch of 291 feet, and a maximum inner

width of 275 feet (Hassell, 1999). The height is only 3 yards shy

of a football field. The creek bed under the bridge is at 3654

ft, and the full level of Lake Powell, into which Bridge Creek now flows,

is 3700 ft. This means that under full conditions, much of the bridge’s

natural height is obscured by the waters of Lake Powell.

We

hiked on, and crossed through the Park Service gate, where signs clearly

indicate that it is forbidden to do much of anything within the park, such

as swimming, camping, fishing, rock-climbing, boating, etc. I jokingly

commented that we shouldn’t breath too much either. The afternoon sunlight

was brilliant, and it lit up Rainbow Bridge in harsh, raw light that contrasted

deeply with the deep, dark shadows on the walls and below in Bridge Creek.

As we approached the bridge, a rock wall on the right held two large copper

plaques, one commemorating Jim Mike and the other Nasja Begay, the two

Native Americans present when the first white men viewed Rainbow Bridge.

I had read previously that the Park Service requests visitors to refrain

from walking under the bridge in respect of Navajo religious beliefs. Much

is written on Park Service placards and brochures about how sacred this

site is to the Native Americans, but I question that. For example, when

rumors of the bridge came to Anglo ears in about 1907, they contained language

like, “only a few go there”, “not remember the prayers” or “not many know

the way”. When Byron Cummings and William Douglass, two Anglo expedition

leaders, sought guides for this rumored bridge in 1909, they could find

only a few Native Americans who had ever even heard of the bridge, or at

least who would admit to knowledge of it. The expedition leader from Utah

State University, Byron Cummings, hired a Navajo named Dogeye Begay, while

Douglass, a General Land Office employee, hired a Piute called Jim Mike.

After several days of searching, neither was able to guide the expeditions

anywhere near the bridge, since neither had never actually seen it. Only

the appearance of Dogeye Begay’s father, Nasja, saved the now-joint expedition

from collapse since he alone seemed to know the way (Hassell, 1999).

I don’t want to step on any toes, and if someone decides something is sacred,

that’s their right and I don’t have a problem with it. What I’m saying

is that the picture the We

hiked on, and crossed through the Park Service gate, where signs clearly

indicate that it is forbidden to do much of anything within the park, such

as swimming, camping, fishing, rock-climbing, boating, etc. I jokingly

commented that we shouldn’t breath too much either. The afternoon sunlight

was brilliant, and it lit up Rainbow Bridge in harsh, raw light that contrasted

deeply with the deep, dark shadows on the walls and below in Bridge Creek.

As we approached the bridge, a rock wall on the right held two large copper

plaques, one commemorating Jim Mike and the other Nasja Begay, the two

Native Americans present when the first white men viewed Rainbow Bridge.

I had read previously that the Park Service requests visitors to refrain

from walking under the bridge in respect of Navajo religious beliefs. Much

is written on Park Service placards and brochures about how sacred this

site is to the Native Americans, but I question that. For example, when

rumors of the bridge came to Anglo ears in about 1907, they contained language

like, “only a few go there”, “not remember the prayers” or “not many know

the way”. When Byron Cummings and William Douglass, two Anglo expedition

leaders, sought guides for this rumored bridge in 1909, they could find

only a few Native Americans who had ever even heard of the bridge, or at

least who would admit to knowledge of it. The expedition leader from Utah

State University, Byron Cummings, hired a Navajo named Dogeye Begay, while

Douglass, a General Land Office employee, hired a Piute called Jim Mike.

After several days of searching, neither was able to guide the expeditions

anywhere near the bridge, since neither had never actually seen it. Only

the appearance of Dogeye Begay’s father, Nasja, saved the now-joint expedition

from collapse since he alone seemed to know the way (Hassell, 1999).

I don’t want to step on any toes, and if someone decides something is sacred,

that’s their right and I don’t have a problem with it. What I’m saying

is that the picture the  Park

Service paints of regular visits to Rainbow Bridge by masses of Native

Americans for the last several centuries in a sort of Mecca pilgrimage

just doesn’t seem to hold water. The historical record shows it is

more likely that some natives visited it occasionally, but the majority

never did. Personally, I don’t see how walking under or approaching

Rainbow Bridge is disrespectful. I didn’t walk 13 miles through canyons

to disrespect a piece of rock. I walked 13 miles to see a natural creation

of beauty, and I don’t think that any position of my body means much at

all to the rock. In 1995, a group of Native Americans calling themselves

“Protectors of the Rainbow” barricaded the trail to the bridge, and protested

with signs the deplorable standard of living on the Navajo Reservation.

Some were photographed climbing on top of Rainbow Bridge. Is that religious

reverence, to use Rainbow Bridge to promote a quasi-political agenda? Nevertheless,

Dave and I walked up a hill and around the east end of the bridge, and

down the other side, probably contributing much more to erosion than if

we had simply walked underneath. It all seems so politicized and, frankly,

ridiculous. Park

Service paints of regular visits to Rainbow Bridge by masses of Native

Americans for the last several centuries in a sort of Mecca pilgrimage

just doesn’t seem to hold water. The historical record shows it is

more likely that some natives visited it occasionally, but the majority

never did. Personally, I don’t see how walking under or approaching

Rainbow Bridge is disrespectful. I didn’t walk 13 miles through canyons

to disrespect a piece of rock. I walked 13 miles to see a natural creation

of beauty, and I don’t think that any position of my body means much at

all to the rock. In 1995, a group of Native Americans calling themselves

“Protectors of the Rainbow” barricaded the trail to the bridge, and protested

with signs the deplorable standard of living on the Navajo Reservation.

Some were photographed climbing on top of Rainbow Bridge. Is that religious

reverence, to use Rainbow Bridge to promote a quasi-political agenda? Nevertheless,

Dave and I walked up a hill and around the east end of the bridge, and

down the other side, probably contributing much more to erosion than if

we had simply walked underneath. It all seems so politicized and, frankly,

ridiculous.

When we reached flat ground,

we were confronted with a herd of people gathered behind a stone barricade

that we were now on the wrong side of. Rainbow Bridge also serves as a

gateway, holding back the Park Service signs, pavements and shelters that

litter the west side of the bridge. Dozens of brown and white signs proclaimed

“Area Closed” and “We ask for your voluntary cooperation in not approaching

or walking under Rainbow Bridge.” We got a few stares as we stepped onto

the paved Park Service viewing area, but heck, how else do you get to the

other side if not by crossing this line? We asked a guy if they were with

the tour boat, but they weren’t, so we decided to walk down to the dock

to meet the tour boat that was supposed to arrive at 3:00 and see if we

could alter our reservation for the following day. Along the wide,

flat,  boulder-lined

trail leading down canyon, I stopped to take several photographs of Rainbow

Bridge with snow-dusted Navajo Mt in the background. Every 50 feet a Park

Service sign proclaimed “Area Closed”. I was frustrated at the ugly signs

and their unavoidable presence. In one photograph, I had Dave stand in

front of a sign to hide it. The trail was very deliberate, with obvious

signs of heavy earth-moving equipment use and backfill. Tire tracks criss-crossed

the trail. Slopes of rock seemed out of place. The lake was very low, the

lowest it had ever been since it reached full level at 3700 feet in June

of 1980, and the thirty or forty feet of white scum on the rock above the

waterline, the bathtub ring, showed the high point. Dozens of steel hooks

and rusted cables hung limply from the walls, dock anchor points from previous

high-water years. Steel culverts and PVC drains channeled water under the