| The Lost Coast

Location:

King

Range National Conservation Area, between Shelter Cove and Eureka, CA

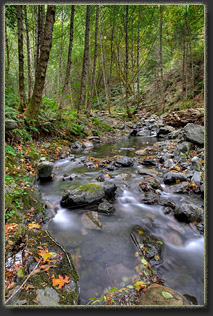

View Larger Map The road to Shelter Cove is a thin blacktop with no shoulders threading through stands of Douglas fir as it heads up and over the King Range, and is perhaps the windiest paved road Iíve ever driven on. The awkward Mazda rental car, a kind of small minivan, sways like a squishy beast at every hairpin curve, forcing me to slow down well below the 35mph speed limit. I canít imagine anyone doing the speed limit on this road. Just as I think that, truck headlights rear up in my rearview mirror like a pair of snake eyes ready to strike, and I gently pull off the road at the first pullout to let the small, dented gray truck zip past like a racer. Must be a local. The windy road is kryptonite to Andra, and her only defense is to go to sleep, which she accomplished about 3 minutes into the curves outside of Redway. I listen to the soothing voice of Nora Jones as I work the steering wheel back and forth like a coxswain on a frigate and roll down the pavement in 2nd gear into Shelter Cove. We stop at the general store, and I mean THE general store. Shelter Cove has lots of homes, but very few businesses. This general store is the only place to get any sort of groceries or gas, as far as I can tell. I head in, grab some caffeinated beverages for us (better living through chemistry) and weíre off again down the road to Beach street, which leads us, fittingly, to Black Sands Beach and the start of our hike. We park the vehicle in the large lot that looks familiar from my perusing of Google Earth before the trip. We take a few minutes for last minute packing, and Andra shakes off her car-sickness. The sky is grey, and Iím hoping fervently itís just morning fog that has yet to burn off. Even though itís 10:30. A few moments of confusion follow as we approach the west end of the lot to find no way down to the beach. After some fumbling around, we figure out that you have to walk east to the parking lot entrance, down the road, and turn west to walk down the road to the trailhead. Finally, weíre on the beach, heading across a wide expanse of dark gray sand towards the white foamy waves crashing beyond. The sand is difficult to walk on, and I am glad we have plenty of time before high tide so we can take advantage of walking on the wet sand below the tide line. I expected the sand, but I am surprised at the amount of cobble. Millions of smooth, polished gray stones cover large swaths of the beach. I walk some on the cobble, some on the sand; if one is easier going than the other, itís not apparent to me. We stroll along the beach, delighting in the waves crashing just feet away to our left. Nervous seagulls strut away from us as we walk north, and usually resort to taking off into the wind when we approach within 40 feet. Andra wonders aloud why seagulls could possibly be so worried about hikers here, since itís almost inconceivable that any hikers have ever harmed local seagulls. I agree. Why are those seagulls so skittish? We cruise along and the beach narrows as we head north. Soon there is only a 50-foot swath of beach to hike on. East of the beach, steep banks of aggregated clay and stone rise up, usually barren, and usually too steep to ascend. Occasional breaks in the banks occur with grassy plateaus and stockpiles of bleached driftwood, washed in by storm surges. We pass through a corridor formed by several house-sized rocks, scampering quickly between two of them to avoid a large incoming wave. Just beyond we come upon Horse Creek. We stop at a grassy plateau in a break in the cliffs and sit on a huge log to survey the scene. Itís 11:30 and still cloudy. This is no morning fog. Itís 51 degrees, which feels plenty warm enough, so perhaps itís OK that the sun is not out. We watch the ocean, which seems rather mellow. Andra spots the shiny heads of seals bobbing in the water just offshore amongst the kelp, staring at us with huge black eyes that seem to have no white. On we go, up the beach. There is no particular destination, so we take it slow, stopping often to watch the water. The peaks of the King Range are hidden in low-hanging clouds that skulk no more than 1,000 ft above the beach. Shortly before Gitchell Creek we stop in a grassy break in the cliffs and have a snack. The sun seems to come out, and we actually see blue sky to the north. I put on sunscreen. Too much optimism: within 20 minutes all hint of sunshine is gone again, and Iím left with greasy skin. While low tide allowed it, we walked on the wet sand, but around noon the tide is rolling in towards high mark and covers most of the sand. Despite the lack of a formal trail, there is often an informal path of least resistance, usually up near the vegetation. We stick to this when the cobble on the beach gets too large to comfortably walk on. Massive logs, veterans of some long-ago storm that washed them out to see and back again, dot the beach at intervals. While walking around one such long trunk, a snake greets us disdainfully by coiling up and striking out. Itís not a rattler, and Iím sure itís not poisonous, but itís fiercely aggressive and seems to plant itself firmly in a coil. We clamber over the giant log and go around. A cleft in the cliff face comes into view, from which issues Gitchell Creek. A small pond, fetid with scum and bird feathers, marks its terminous as it drains through the cobble and into the ocean. There is a driftwood hut of sorts on the south side of the pond, in which two men are sitting. I watch them to greet them if they turn around, but they donít. I consider greeting their backs, but the stiff south wind would require me to literally yell to be heard, and it seems incongruous with the surroundings to yell here, so we simply walk by, unheeded until we are well past. We decide we might stay here tonight, so I want to scope out the creek for potential campsites. Andra sits down on a log near the creek, and I head upstream. Above the little pond, clear water rustles beautifully along a cobble channel lined with alders and willows. I duck and weave among the low-hanging branches up a little social trail that bends with the sinous turns of the creek. I find a flattish spot where somebody has built a fire ring, but it is not large and seems an odd place to set up a tent. I hike on a little farther, but the canyon is narrow and lined thickly with alders, providing no campsite potential, at least not without a long hike up canyon. Returning to the beach I find Andra has gone. I hike up north a little, thinking she has gone ahead. Still no Andra. I check out a few potential campsites among the driftwood on my way back, and find her dozing in the shade of willow right beside the rushing water of the creek, so well camouflaged in her faded hat and tawny-colored hiking clothes that I had walked within 15 feet of her without noticing. We decide to set up camp on the beach, and I walk north about 120m from the creek to a flat spot well above the tidal zone that is somewhat protected from wind by two large logs set at a right angle. I set up the tent. Itís no small feat to set up a non-free standing tent in loose sand. In such a situation tent stakes are worthless. I use lots of rocks as deadman anchors and a few large branches as uber-stakes. Just as I get the tent fabric taut, I hear the dry rattle of semi-automatic gunfire. Downbeach, just south of the creek, the two men we had seen at the driftwood hut have become four, and one of them is kneeling behind a log and shooting the hell out of the bluff. Andra, shaken out of her reverie by the creek from the soft sounds of gunfire, walks up with her pack and we sit on the giant log, pondering our options. Camping 150m away from men firing semi-automatic weapons for fun is not what we had planned on our wilderness backpacking trip. I pull out the tuna, crackers and trailmix and we have a small lunch. The tuna is salty and delicious. As we sit watching the ocean waves crash on the beach, a second man from the group, dressed in camouflage, produces a pistol and begins firing about 10 shots into the bluff near the creek. The reports echo down the cliffs towards us. We bide our time, and Andra believes they are packing up camp. I canít tell. I decide to find out and I walk over to talk to them. I bring my map and strike up a conversation with the four men about the tides and how high they run up the beach, particularly in the ďimpassable zoneĒ. They assure me the area Iím in is safe from high tide but comment that the impassable zone is correctly named during high tide. I thank them and walk back to Andra with full confirmation that they are packing up camp and about to leave. Ten minutes later, they have their packs on and are fading into small dots down the beach. We roll out our pads, bags and stuff all the food into the bear canister, which is, BTW, required equipment in the Lost Coast NCA. The clouds thicken up, and Andra decides to take a nap. She is abnormally fatigued, whether from the car sickness or a cold is not clear. While she snoozes in the tent, I walk around camp. High tide is in. I explore the bluff behind camp, and find a game trail that leads up a steep tallus slope into the tanoaks and Douglas fir. I get up high enough to look down on camp and see far out across the leaden-colored ocean. A ceiling of grey clouds extends endlessly in every direction. I walk up the beach about half a mile and find a great camp above the beach in a grassy flat nestled in a break in the cliff face. If we hadnít already set up camp, Iíd have moved it here. Nice spot, and out of the wind. My progress back down the beach is followed by a cadre of curious seals, their heads bobbing just offshore, watching closely. Several seals bask on rocks just offshore. Amongst the flotsam near the tideline, I find 2 sticks, weathered smooth by sand and bleached to a light grey, that look like foot-long gnarled Harry Potter wands. I take them back to camp to show Andra. When I return to the tent, it is 4:00 and Andra is awake, reading the final pages of her paperback. We hike up Gitchell Creek a ways, enjoying the sudden verdant lushness of coastal forest after the austere rock and sand beach. White-barked alders lean in over the rushing water that runs clear over dark gray rocks, while ferns hang down off every rock face. There is a nice campsite about 500m up the stream, right where the stream takes a pronounced north turn, but again, weíve set up camp already, and anyway itís nice to hear the ocean at night. On the way back downstream we startle a doe that gallops off up the slope. We stop and watch her go, and a moment later, a fawn breaks cover and runs after her. In camp, at 5:15, we crack open the bear can and eat dinner of sausage, cheddar, crackers, dried bananas and apricots and Snickers bar for desert. Quite a feast. Itís chilly, and we sit down against the big log by the tent to read and watch the ocean. Several hiking groups trudge by, all heading south. Of the 9 hikers we see today, all are heading south. One hiker approaches us and says hello, then introduces himself as Paul, the wilderness ranger. He digs our bear canister and we pass the quiz on where to take a shit (below tide line, in a cat hole) and then heís off. Around 6:30 we take a walk up the beach and watch seals on the rocks, seals diving off the rocks and?most comically?seals trying to get up on the rocks. They may be graceful in the water but they are slugs on land. Back at camp, I head to Gitchell Creek, hike upstream a ways, and filter water. Then I fill up my collapsible bucket and walk as far away from the creek as the narrow canyon permits to bathe. Itís chilly, and my skin erupts in goose flesh. Without a stove to heat the water, I get it over with as quick as I can. Weíre in the tent by 8:00

as dark descends. Nobody has come to camp near us, and the only sounds

are the waves crashing on the beach about 50m away, and a chorus of frogs

that has come to life up in the creek. The clouds shroud the beach and

mountains, so that no sky is visible, and the darkness is overwhelming.

Itís quite chilly and damp, and I sleep wonderfully.

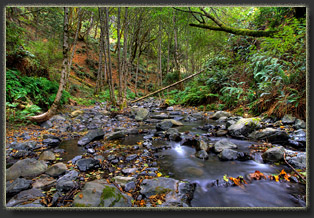

Sept 8 With every intention of sleeping in, Iím awake a little after 6 when it begins to get light. Andra is reading her book quietly next to me. In the cramped confines of this so-called two-man tent, I struggle to get dressed. I unzip the tent and take my first steps out of the tent and into my boots. The sky is cloudy, again, and the air is hovering at 60. It is just a couple hours past low tide, and large swaths of tidepools and ribbed black rock lie exposed, intermittently, between gentle swells of water that pack little punch. The kelp forest offshore seems to absorb and dissipate the wave energy. A seal lounges on a rock offshore and gulls cry distantly down the beach. The smell of salt hangs in the air. Beautiful. Deer tracks lead down from the forest to the waters edge, and then back. I stand and consider why a deer would visit the crashing waves of the ocean, and can find no suitable hypothesis. Andra is up and about, and we crack open the bear can to get breakfast food out: Pop Tarts, dried fruit, the usual deluxe spread. The waves come in higher and higher. A small seal gets swept off a rock, but quickly gets back on, only to be swept off again. The tide is rising and soon the rock will be completely submerged. Must be annoying for a seal wanting a few extra minutes of rest on the rock with the ocean tide coming in inexorably, like an alarm clock with no snooze button. After our own lounging about camp, we head north, with daypack only, at around 7:30. With the tide out, much of the beach is exposed, and it is easy going in the dense, wet sand near the water. Like a sidewalk, the sand is firm and hard underfoot. The beach narrows as we head north, and soon we are forced into a narrow strip of cobble between the water and the cliffs, despite the low tide. At times there is no more than 20 feet of solid land to walk on, all covered with black cobble still wet and shining from last nightís high tide. We pass two backpackers heading south, but otherwise the beach is deserted this morning. Buck Creek is about 2 miles up the beach, and we reach it in about an hour. The break in the cliffs at Buck Creek is very like the break for Horse Mountain Creek, perhaps a bit wider. However, unlike Horse Creek there is no sandy beach to camp on. All possible campsites are east of the cliff face, amongst the trees and grass along the creek. Many flattened campsites are packed in here, though none of them are occupied this morning. I dislike the idea of being ďstuckĒ here by high tide, and am glad we didnít push on to camp here last night. I suggest we hike up Buck Creek trail a ways, but Andra demurs. I hike it alone. She claims she will not leave the creek mouth, like I had perceived she did yesterday at Horse Creek, and since the tide is rolling in and making beach travel impossible, I completely believe the claim. I hike up the crazy-steep trail through maples and Douglas firs. The sky is still cloudy, and in the trees it is very dim, almost like twilight. The air is very thick with moisture, and perfectly calm, with only the distant sound of the creek far below to break the silence. My boots tread quietly on the damp earthen trail. Ten minutes from the beach, I hear a disturbance in the undergrowth, and look down the hillside to see a black bear rambling along slowly through the ferns. I freeze to watch. He continues parallel to the trail for a few strides, then turns and begins to head directly uphill on a game trail that intersects my trail about 15 feet from where Iím standing. I consider pulling my camera off my shoulder and getting it set for a picture, but I know the movement will spook him, and anyway itís so dark I canít take a clear photo without my tripod. Instead I just watch, and enjoy this wild encounter with a black bear, my fourth in life (two in California, two in Virginia, but in all the years of hiking in Colorado\Wyoming nary a one). The bear approaches within about 30 feet of me, stiffens, looks up directly at me, then bolts down the hill away from me in a frenzy of crashing ferns and snapping twigs. I do not see the bear again. On up the trail I go, huffing and puffing, sweating profusely in the humid air. I note a few decent camps along the way, but they are far from water, and sprinkled with poison oak. Not ideal, but if the camps at the creek mouth are full, one could do very nicely up here. I reach the second switchback on a ridgeline above Gitchell Creek, with obvious views to sea on a clear day. As it is cloudy, I see nothing at all but white cloud. Disappointing. I return down to the creek. Andra is watching waves crash when I return. Still nobody about. The high tide keeps this place private for us from all beach traffic. We both read for a bit, then sit on a large log near the waves and watch them pound the rocks and slide up higher and higher up the cobble towards us as the tide rolls in. Andra lays down on the ground higher up and naps. I sit on a grassy point of cliff from which I can watch the beach both north and south, and admire the waves crashing and the seals swimming offshore. I ate my lunch of tuna, crackers and Snickers, and read my book. I am conscious of a delicious slowdown in the pace of life today. Itís very relaxing. Andra awakes, and I take my turn lying on the ground and napping. After 45 minutes I wake up with very cold hands. I stroll over to the grassy bench south of the creek to find Andra quietly watching a family of otters frolic in the waves. She had watched them emerge from the creek and cross the cobble beach to get to the ocean: two adults and three pups. Now we see them bobbing in the water. We hike up the creek, but donít make it far. Downed trees and generally rough terrain force us up out of the creek channel on to the bench above, to the north. We find a rock chimney, the building it once heated is long gone. Poison oak grows in a forest all around, preventing further exploration. I find a game trail that leads steeply to a higher grassy bench that, once Iím on, leads easily to the cliff above the beach on the north side of Buck Creek. I see lots of deer sign, but no sign that humans have camped here. The difficult climb up explains why. Andra and I return to the beach and watch the ocean. An otter emerges from the waves and walks around a bit on the beach, checking us out and clearly worried. He returns to the water after 10 minutes. Voices approach from behind. Four backpackers arrive, noisy ones, and we decide that the tide is low enough to leave. Weíre off, down the beach back to camp. We reach our empty stretch of beach at 4:00 under a still-cloudy sky. I am powerfully disappointed that the sun is not making any showing. All my visions of beach camping over the last year involved blue water, white wave crests shining brightly, gleaming sand, blue sky and, of course, a burning Pacific Sunset enjoyed from the open flap of the tent at night. And if I should get a little red shine on my nose from the UV I wouldnít mind so much. Well, no such luck. The sky is the color of molten lead. Far to the south I can see the point of Shelter Cove jutting out into the ocean, also blanketed by clouds. Somewhere, far above us, I can picture a brilliant white downy bed of sun-drenched cloud-tops with blue sky overhead. Itís hard to remember that itís up there somewhere. We content to wear our warm clothes, knit caps, and sit huddled by the giant conifer log next to the tent, watching the ocean and reading books by turns. As if someone has opened a gate (the tide, in essence, had opened the gate), a steady trickle of backpackers appears from the north, 18 in all, including the four we encountered at Buck Creek, bringing the daily total to 20. Four men appear with rifles and shoot them off into the bluffs north of camp, reason unknown. The continue down the beach and out of sight. Another 2 men arrive near 6:00 bearing rifles and set up camp in the driftwood hut south of the creek outlet, but thankfully do not feel the need for target practice. We have a wonderful dinner of sausage, cheese, dried fruit, trail mix and Snickers. More reading. Andra finishes her book and begins reading an e-book on my phone. Just after low tide, we explore the tidepools. Alien creatures like anemones and starfish rise out of the water with each wave pulse, and are gently covered in turn by the rising water that follows. Not as many starfish around here as Iíd thought there should be. Iíve heard of starfish die-off in California. Perhaps I am seeing it tonight. The sun shines briefly on Shelter Cove to the south, but in less than 20 minutes the sunshine is gone. I haul a bucket of cold creek

water to camp and wash my face and some clothes. It is too chilly to wash

anything else. Andra is curled up in her sleeping bag by 7:30. Gray dusk

slides in and I lean against the big log, watching the ocean, the sky and

feeling hidden. I read my book. Seals lie on the rocks offshore. Shorebirds

screech through the muffled damp air. Itís about 55 degrees, though not

very breezy. Still, I find it comfortable to wear 2 shirts, fleece, boots,

pants and a knit cap. By 8:00 itís dark, and I retreat to the tent to read

by flashlight for a brief time before sleeping a long night without disturbance.

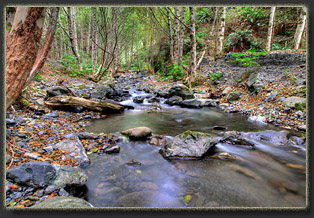

Sept 9 We wake, we dress, we pack camp. The simple ritual of a backpacking morning is soothing. In unusually thick fog that obscures every feature beyond 50 yards, we head south with our packs. Breaks in the fog reveal the tops of the peaks for the first time this trip, but each vision is fleeting as the fog wafts back in. Near Horse Mt Creek the sun comes out for about 10 minutes, casting actual bonafide shadows on the sand, but then disappears. At Horse Mt Creek, Andra shucks off her shoes and leans against the log near the outlet pond on the beach and snoozes a bit. The sun comes out weakly, warmly. Itís nice. I hike up to explore Horse Mt Creek a bit and to filter water as far up in the drainage as possible to avoid potential human waste contamination. I like it a lot. The alders and the ferns look so inviting, especially with a warm glow of sunshine streaming in through the thin fog. If not for travel obligations, Iíd be content to pitch my tent right here and stay another night. Itís bittersweet to leave the inviting forest, knowing that in this short life, Iíll likely never see this spot again. We continue south, passing groups of nervous seagulls and a few magnificent black ravens perched on the long-dead and sand-smoothed branches of a giant tree. The fog slides north in shreds and tattered clouds, leaving the sunshine to wax and wane in a semi-rhythmic pulse of light and warmth. The effect is otherworldly, at least to someone from the mountain west, like me. The cobble at low tide is arranged unevenly, in little arrowhead-shaped aggregations that point out to sea, spaced along the beach at intervals of about 50 feet. Between the cobble piles there is only open sand. I surmise the wave action must be responsible for arranging the cobble so, but I canít quite figure out why. In areas of heavy cobble, the outgoing wave pulls the rocks down the slope, out towards sea, and they clatter against each other in their millions to create a crescendo of knocks and cracks that begins to sound like the beach is ripping apart from the bedrock, rising to an alarming level just before the next wave pounds in and sends the cobble back up the beach to start the thing over again. By 11:30 we are at the trailhead.

Sunshine is warming the sand on the beach where we stand, and to the south.

The north offers nothing but beach for 100 yards, then impenetrable fog.

We throw our packs in the car and drive off to the Inn of the Lost Coast

for a fabulous shower, a dynamite pizza from the adjoining bakery that

opens at 1:00, and a wonderful relaxing time on the balcony overlooking

the ocean, where, ironically, the sun shines uninterrupted all afternoon

(though the Lost Coast to the north, aptly named, remains obscured

in fog until just before sunset.

Sept 10 Around dawn, we get up and get moving. It's a long drive back to San Francisco, and the flight will leave whether we're there or not. We have coffee and danishes in the coffee shop immediately below our room, then walk over to the rocks and enjoy half an hour watching the waves crash on the rocks. I only see the ocean about once every 2 years, so there's a need to tank up on surf viewing. On the way out of town, we stop at the TH again and from the railing above the beach, admire the view to the north where the entire length of our previous 4 days' hike is perfectly visible under a clear and cloudless sky. Then we pop in the rental and head east. |

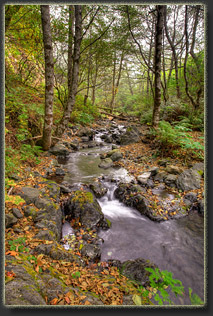

Gitchell Creek

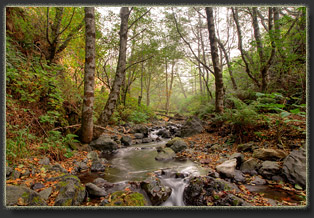

Trail up Buck Creek

Buck Creek

Looking north from bench above Buck Cr

Relaxing at camp

Gitchell Creek campsite

Last night in the tent

Horse Mountain Creek

End of the hike

Relaxing at Shelter Cove

Sunset from Shelter Cove; King Range peeking in on the right

The Lost Coast from Shelter Cove

The view from the south TH to Miller Flat |