| Gardner Mountain

Wilderness Study Area

Ice Cave to Bear Trap Creek & Red Fork Powder River Location:

Gardner Mt WSA, west of Kaycee, Wyoming

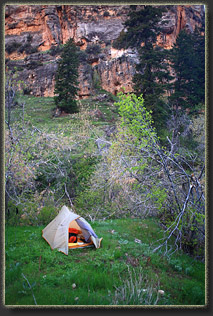

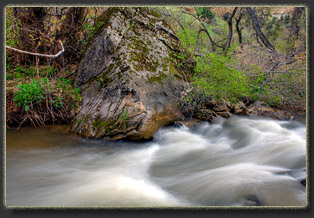

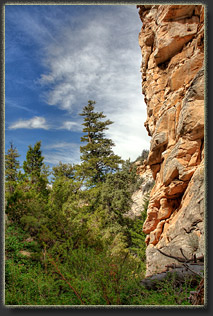

View Larger Map Itís late May in Wyoming, and you never know if a day will bring freezing wind or baking sunshine. I step out of the car at 8,200í on the north end of Gardner Mt, to something in between. A stiff breeze is blowing, but the sun is out. In other words, itís about as perfect as one can expect. I stretch off nearly 4 hours of stiffness from sitting in the car from Cheyenne. I strap my tent to my pack, lace on my boots and lock the car doors. I sign in at the trail register, although the trail register only wants to know what youíre doing and how long youíll be doing it. No name asked for. Through the gate, and Iím on a two track that leads uphill towards the rocky ridge of Gardner Mt. Lush Douglas fir festooned with dangling cones and bushy limber pine form a thick forest to the east of the track, but to the west the country is open with low grass and white-flowered phlox up to the ridge. I head on up, and examine the country beyond from my lofty perch. The rock cliffs drop away for a bit, then lessen to steep slopes of grass for a thousand feet to the bottom of Cottonwood Creek. The land tilts from there upwards to the west like the old Labyrinth marble game at full tilt, with numerous drainages lined with trees bisecting the plane. Beyond that, after another dropoff, the pattern repeats, on into the haze of the horizon. There is substantially little evidence of human settlement. The only sign of human touch at all is the barbed wire fence stretching though the green pasture below. A thick bank of snow bars the way, but I carefully stomp through it and after 20 feet Iím on the other side. The shade of the trees is deep momentarily, but soon Iím back out on the green slopes of the mountain, east of the ridgeline, walking south. In the distance a trail marker is staked in the open, with hardly a visible trail near it. Indications are this trail gets very little use. The ridgeline is mostly forested with limber pine, and I canít see my destination except at rare intervals. I pass through an open gate, the kind youíre supposed to close after you walk through; however, since the wire fence is smashed down for 30 feet to the east, I see little point in closing the gate. I consult the GPS and the series of waypoints Iíve programmed in that mark private property corners, and shortly after the terrain looks good for a descent towards Cottonwood Creek. Itís crazy steep, and of course there is no trail or even an easy route. A thick forest of bitterbrush makes the going tricky. Itís hot enough for shorts, but I begin to wish I had pants on as the stiff branches scratch my legs with each step. I make my way for a private property corner, and descend a steep drainage with very deep layer of duff that pads my footfalls and makes the hiking easy. The sky clouds up. The distant roll of thunder sweeps in from the north, but the track of the clouds assure me the center of the storm is well to the north over the Bighorns. I continue downhill, trying to stay south to avoid the private property. I reach Cottonwood Creek, which has neither cottonwoods nor water (some creek) and find myself in a deep ravine that I have to climb out of with considerable effort. The route Iím taking into the WSA is complicated by the presence of unmarked, unfenced private land which I am trying to steer clear of. There doesnít appear to be anyone around who would notice, but partly out of the challenge of navigation, I attempt to remain wholly on public land. This involves deviating considerably from the easiest route, and instead giving up a lot more elevation than otherwise would be warranted in order to reach the WSA by going far downstream Cottonwood ďCreekĒ before turning west and heading up the tilted plane towards Bear Trap Creek. In a way, the private land is probably what keeps this particular corner of default wilderness so wild, as it is more difficult to get to than most people will accept. The difficulty of the journey is exactly why I am so keen to see this place. That and a big olí canyon. Love those canyons. I slog uphill on a grassy flat slope bounded to the north and south by shallow canyons whose walls are made of a kind of rock that shears off vertically, leaving very few places to get in or out of the canyon. Because extrication further up either canyon is uncertain, I decide to remain on the high ground, even though it seems to be taking me further north than I really want to be. Iím heading generally west, but I want to be going southwest. As the canyon reaches its upper terminus, and the cliffs are not as dominating, I cross over to the south side of the southern canyon Iím following, and continue southwest across another wide open plain of grass and forbs. From this area I look back to see the dramatic and perhaps rarely seen flatirons of Gardner Mountain. They remind me strongly of the Ferris Mountains near Rawlins, and are probably of the same geologic origin. When the sun occasionally shines through a break in the cumulous thunderheads, the white rock of those flatirons glows. I cross a two track at 5:00, and I am now inside the WSA, after 3.5 hours. I finally reach the top of the long plain at a ridgeline dotted with limber pine, and now I encounter a scene similar to the one I had when I first started the hike. To the west, a large drop in the land, leading down another thousand feet to the plain below, which is also uplifted to the west, bisected by many drainages. The most significant drainage by far is that of the North Fork of the Powder River, which is a deep gash in the earth heading west, within which almost every surface is covered with conifers. This is the other significant obstacle to getting into Bear Trap Creek: To hike in you drop 1960 feet, hike up 1000 feet, then drop again 1600 feet to reach the canyon bottom. Itís like two hikes in one, and from TH to river confluence you'll be hiking downhill 3,560 ft to achieve the net loss of 2,550 ft. The sky to the west grows more threatening, and the wind is kicking up. So far Iíve been lucky to watch all the big thunderstorms pass to the north, but there is an ominous black mass of cloud heading my way. I quicken my pace. Iíve gotten to a point on the map where prior research of aerial photos and topographic maps did not yield a clear descent into Bear Trap Creek, and I am now in the position of winging it down. The first deep canyon I come to has burned recently, and every tree is scorched and blackened. Simply by the melancholy look of the place, I pass it by. The second canyon I come to seems like it will lead me too far east and into private land. I originally thought I might be able to descend this canyon for a little while, then jump out of it and head due west, but upon reaching it I see that a hiker could not easily get out of this canyon to the west. So, on to the third canyon, where I see that the way down is steep, but apparently possible. This is the easternmost of two canyons that join together about a quarter mile above Bear Trap Creek. I could continue on to the westernmost canyon, but I feel it will look much the same as this one, so I start descending. The bitterbrush in the head of this canyon is phenomenally resistant to intrusion. Like an armed phalanxe, the stiff branches scratch my body from shoulder to ankle, and push back against me with force all out of proportion to the small size of the branches. Through slow growth and long years, the wood of the bitterbrush here is tough as steel, with the tiniest branches hardly yielding at all. I shove and bull my way downhill through the sea of branches, pushing them away from my face but taking hits to my cheeks anyway. My legs are soon scratched and bleeding, as are my arms. Frankly, this part of the hike sucks. I mentally vow to find an alternate way back up that avoids this section. I finally reach a point downhill where the terrain levels off a bit and, surprisingly, the shrub density tapers off enough that I can follow game trails with relative ease through the shrubs. I follow the canyonís western wall, which is vertical, but broken in many places. The rain comes my way from the southwest: a grey veil descending on the landscape, soundlessly. I notice a deep cave in the rock wall with a soft dirt floor that slopes upwards as the cave runs back some 15 feet. The opening is about 15 feet high, but only 3 feet wide. I can easily stand in the cave, but I notice the floor is littered with thousands of bones. Not only do I not fancy sitting in bones through this rainstorm, I also calculate that whatever toothed beast(s) has left all these bones might decide to come back if it is raining hard enough, and I really donít want to meet a bear or lion up close in a cave with one opening, so I move on. The first pelts of rain slap my pack with toneless thuds. I find another cave, this one much smaller and bone-free. As a compromise, I have to kneel down to crawl in, but once in I am able to sit up with my back against the sloped rock wall and recline in comfort. Even my pack fits. I remove my boots and air out my feet while the rain envelopes the landscape. Sheets of water come ripping up the canyon, but luckily the wind carries the rain parallel to me and not into the cave. I watch the sky grow almost opaque with silver rain for a minute before it tapers off rapidly to a mere drizzle. I wait until the drizzle was almost done before slipping my boots back on and emerging into the humid air. Itís about 6:15 and Iím starting to feel the urge to be down, to be in camp, to have my tent up and sleeping bag laid out. In short, I am ready to be done hiking today. Still a ways to go, though. Now wearing my rainjacket and full pants, I continue down the middle of the canyon as it narrows up and the sides become very sloped. Every bitterbrush and juniper is dripping with water, and brushing up against them brings a cascade of water down on me. The rocks are slick, and I slip and slide down the slope, using my hiking poles to great effect. Man Iím glad I have hiking poles for this trip! I slip badly only once, grabbing on to a juniper branch as I skate down a slick boulder, and when my arm reaches full extension my body whips around 180 degrees, twisting my leg and wrenching my knee. Going to be feeling that one later. I reach a junction with the second feeder gully that comes in, and Iím glad I chose this one, since the other one has a 15 foot rockfall that would be intensely difficult to negotiate in good weather, and almost impossible when the rock is wet. I see my alternate reality self standing at the top of that rockfall, out of water, only half a mile from the creek, skulking. Iím glad to be down in the main channel, though thereís no guarantee I can make it to the creek even from here. The canyon narrows to no more than 8 feet, with sheer rock walls on either side. Itís very pleasant. Reminds me of the Colorado Plateau, and in fact Iíve reached sandstone here so the resemblance is well-deserved. There are very steep portions that require me to remove my pack and throw it down ahead of me, but I never need to resort to lining it down. Usually the drop offs are not that far down, but hard to do with a bulky pack on. Finally, at 7:00, I reach the creek and its beautiful thirst-quenching frothiness, boiling along at bank-swelling flows from the snowmelt above. Despite the narrowness of the canyon, and the thick tangle of vegetation both up and downstream, I find myself almost immediately in a large, flattish grassy spot, well above the creek and perfect for camp. I kick a few cowpies out of the way and pitch the tent first, eyeballing the ominous clouds skating by overhead. Itís chilly, and Iím wet, so I pull out my heavier jacket as I go about my tasks of loading the tent with essentials for the night. Filtering water is next on the agenda. I find a flat rock near the water to sit on and filter a liter of clear, cold water. I gulp it down at once. Then I filter another 2 liters for later. Dinner was supposed to be Ramen noodles, but itís late and Iím terribly tired. Tuna and crackers suits me fine, followed by some M&Ms. I crawl into my tent and make some notes, study my map and GPS, and finally trail off to sleep around 10:00. At 1:00 Iím up and out of the tent heeding the call of nature. The sky is perfectly clear with no moon to obscure the millions of stars in a pitch black sky. Itís amazing to think that those stars, so far away that their light left their own solar system millions of years ago, could still send out enough energy to light the floor of the canyon well enough for me to see and walk around. By the soft glow of starlight, like bioluminescence, I set up my camera and shoot several photographs of the night sky, hoping for some of the meteors advertised on NPR. None show up. Still spectacular view of the sky. Itís breezy, and despite a milde 45 degrees, feels cold. I hop back into the tent and return to sleep. May 24

I pack up camp, then shoulder my pack and head downstream, thinking I might find a better way out of the canyon than the one I used to get in. Wishful thinking. Apparently a snowstorm hit last fall before the ash, cottonwood and box elder trees had shed their leaves, and the wreckage is awful. Thousands of limbs are down all over the place with dried leaves still clinging to them. In some places I can move the branches out of the way, but many are a foot in diameter and wonít budge. The frame pack makes me clumsy and the darn thing catches on branches and limbs at almost every step. Often I have to crawl on hands and knees to get under limbs, only to get caught by my pack. Having made it no farther than 200 yards from camp in 20 minutes, I abandon the pack and walk on down with just my camera, climbing over the bigger tangles of limbs, or climbing around them when necessary through tangles of clematis and prickly roses. As I near the confluence with the North Fork of the Red Fork of the Powder River (what a name!), the route is made a bit easier by the obvious loitering of cattle, and large areas are trampled down to dust with plenty of shit to flavor the creek water for the landowners downstream. The canyon wall pulls in sharply and meets the water. To continue I have to cross the stream, but again I choose not to take the risk. I had hoped to see the river, but even though I can see the channel only 200 feet away, I canít actually see the water. I return to my pack and assemble my fly rod. Having carried it all this way, I canít bear the thought of not putting it to use. I find a nice big rock overlooking a promising pool, and fish it for a while with several flies. Nothing doing. The water is moving so fast that the fly no more than touches the water before it rockets downstream, skating across the pool in less than a second. No amount of weight allows the nymphs to drop at all in such a torrent, and anyway no fish could be so fast as to catch it. I try a few other places, but the speed and murkiness of the water combine to skunk me. Iím sure fish abound here: nobody else fishes here and the water looks clean; however, this apparently is not a good time of year to try to pull one in. At 9:30, just after filtering more water and taking up my bottles, I leave Bear Trap Creek by the same tortuously steep route I entered by. The first 15 minutes are the worst, during which time I lift my pack up ahead of me, climb up after it, carry it a few feet to the next obstacle, and repeat. Itís very slow going. After 45 minutes I reach the fork in the drainage and take a break in the shade of a juniper, a respite from the sun that is now shining unencumbered. From there I decide to take a chance and look for an alternate route to the plateau above that doesnít involve bouldering my way up the bottom of a drainage canyon, dodging bitterbrush the whole way. I see a game trail that heads out of the drainage to the east, and I take it. Bingo. This little game trail, heavily used by deer, leads all the way up a ridge between two steep drainages, threading beautifully through rock bands until without any real effort other than steady plodding uphill, I am back on top of the lower plateau where the land is grassy and dotted with scattered pines. I retrace my route from yesterday about 900 feet downhill to Cottonwood Creek, which I reach at 1:15. Afternoon drowsiness descends after I snack on tuna and crackers. I wish so much Cottonwood Creek had water. If it did, Iíd set up my tent right here and take a 5 hour nap and camp here tonight. As it is, without water, Iím forced to head all the way back this afternoon. It's a keen disappointment, but there's nothing to do but get moving and forget about it. I head almost straight east up the slope of Mt Gardner. Itís a long slog. Very tiring. I make my own switchbacks to make the 1900 feet of elevation gain less painful, but thereís no way to sugarcoat it with a frame pack on. I hit the ridgeline, but itís still a fairly brisk uphill climb along the ridgeline to the trailhead. A thunderstorm passes north, then the sun comes out again. I am lucky to reach the car at 5:30 without getting rained on. Iím voraciously hungry, so I cook dinner near the car, then note another thunderstorm heading my way. I throw all my gear in the car, and minutes later the rain comes down. I recline in the comfortable dry interior of my car, reading a Mark Twain book, enjoying the streaks of water sliding down the windshield when I look up to observe the stormís progress. Iím far too tired to try driving home tonight, and Iím convinced this is as good a place as any to camp a night. As the rain continues, I decide to skip the idea of pitching my tent nearby, and instead simply roll out my sleeping back in the back of the Forester and sleep there. Less work, and plenty comfy besides. May 25

|

Looking southwest into Bear Trap Creek. The canyon on the horizon, center-right, is the South Fork Red Fork Powder River

Rain heads in from the SW

Looking south from The Crevasses

Descending a narrow canyon into Bear Trap Canyon

Cozy campsite in Bear Trap Canyon

Bear Trap Canyon

Bear Trap Creek

Bear Trap Canyon

Looking SW to The V, where Bear Trap Creek meets the N Fk Red Fk Powder River

Gardner Mt from the west

Typical route through open forest west of Gardner Mt

From Gardner Mt, looking south along Cottonwood Creek

More interesting views from Gardner Mt  |