| My

Summer as a Firefighter

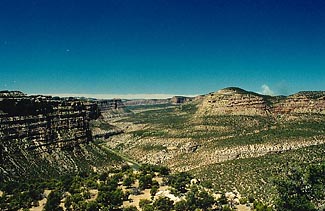

Dinosaur National Monument 2001 Although my job title

was “Fire Effects Monitor” I didn't ever think I would be fighting fires

when I signed up, however; I wasn’t disappointed when it became clear that

there was some expectation of this duty. In early college I had toyed with

the idea of fighting forest fires. The idea seemed adventuresome, and for

a good cause. Trees are a good cause, right? I even had a black and white

newspaper photo of a man in fire duds spraying a stream of water up at

an angle, presumably at the base of some towering inferno. My enthusiasm

for the idea waned as I came to learn that fire wasn’t some evil thing

that struck out wantonly at nice green forests. I came to see To fight fire for the government, you have to have a good pair of fire boots and a red card. To get a red card you have to go to basic fire school (termed “Basics for Survival” or something like that) and pass the pack test. The first thing I did was buy my fire boots, a slick black pair of all leather Redwings, 8" high with a 2" vibram heel. They have no cushioning or padding inside because that stuff would melt onto your skin if you walked through smoldering ashes. Likewise, there is no steel shank or toe, since that would conduct too much heat onto your foot. Amazingly, I never got a blister from these boots. They cost $180, but I was assured that I could make that money back in one fire. I did. The second thing

I did was take the pack test. On the first morning of June, 2001 I drove

to Vernal, UT where I met about a dozen other folks, mostly guys my age,

meeting for the same reason at the track of the middle school. Some people

had brought their own packs to wear, including me, but I liked the option

the BLM procters offered better: a fishing vest loaded with steel plates

on the front and back. This made the weight more uniform, and was better

balanced.

The final requirement was to attend the fire school. I was not the only park employee to do this. Madeline was a seasonal employee working on peregrine falcon mapping and observation. Dinosaur National Monument has a relatively high concentration of these endangered birds, and quite a lot of effort is put into counting the breeding pairs, locating nests and keeping track of how many eggs, chicks and immature birds make it into the world. Tracy and Elen were student conservation association volunteers (we called them SCA girls) who were both working with Madeline. Elen was from New Jersey, I think (maybe DC?) and Tracy was from Michigan. Elen helped me out on the vegetation monitoring at Thanksgiving Gorge later in the month. These were the park employees who I carpooled with from my side of the park. From the quarry side (west sdie) there came two archeological seasonal employees, Ross and Shelby, also my age, who I enjoyed talking to, but never saw again after those few days of fire school. It’s a big park, and I never had anything to do with archaeology, well not officially anyway. The other two guys who attended with park affiliation were sons of permanent park employees, both in high school. One was the head ranger’s son whose older brother Eric was an experienced firefighter now training for helittack duty. He was very much into kayaking and snowboarding and talked like a surfer. I’m not sure where the other guy came from, but he was a sorry guy. Overweight, out of shape, brooding, negative, always frowning. I thought he might as well curl up and die since he hated everything and everyone so much. Park employees and affiliates made up a very small portion of the class, which spent three tired days in a small auditorium at Roosevelt High School in Vernal. By far, forest service seasonal firefighters, most barely 18, dominated the group. They were all hired by Ashley National Forest, which encompasses the Uintah Range in UT. You could spot them because they had the snappy green nomex pants which they chose to wear to sit in class (I wore shorts...it was hot in there!). That and they all stuck together like a clique. Several people from the BLM and the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) were also there. The goal of the class, as far as I could tell, was to scare us shitless about fire, then tell us how to survive it if we got caught in it. A few moments were spent on how to actually put it out as a matter of form. I guess most people understand how to put it out before they ever set foot in a classroom. There were moments of fun, however. My favorite presentation was by Rowdy Muir, the BLM FMO (Fire Management Officer) for the region. Rowdy was quite a character. He had a belt buckle as big as a softball, pointy-toed high-heeled boots, a stiff flat-billed ball cap he wore perched high on top of his head, and he spoke with a crazy hick accent that was fun to listen to. He introduced me to the phrase “going gunny sack”, which means going poorly, as in “When things start going gunny sack, you better know how to get the hell out”. He also amused me by his constant ability to work Wal-Mart into his instructions on fire behavior and safety, as in, “The best safety zone there is, is the Wal-Mart parking lot.” Rowdy was in charge of a BLM fire crew that got in over their heads on a prescribed burn that ended up scroching hundreds of acres at one of my favorite spots in Pot Creek later in the summer, but that's a different story.

On the fourth day, we had some fun. Everyone met extra early in Vernal and boarded a big blue bus bound for the Uintah Range northwest of town. There was snow on the ground along the road we drove up. Our camp was very close to Flaming George Reservoir. We pitched tents and were assigned squads. I was assigned to Squad 2 with Greg and Trevor among the eight of us, these two standing out as being the most positive and negative in the lot, respectively. Greg was a fantastically nice guy - all smiles, very encouraging, humble. He looked a lot like Loyd Brawn from Seinfeld. He was here without official backing yet, hoping that his red card would gain him employment if the BLM or Forest Service got pressed for firefighters. In other words, he was still volunteering and not getting paid. The other fellow, Trevor, was a complete ass. He found inumerable ways to show this personality trait off to everyone. I disliked him immediately. We rotated to different stations located among the trees around camp, each one housing a piece of equipment we would have to know how to use, someday, maybe. Since we could only spend 15 minutes at each station, they were but brief introductions. We visited an engine and sprayed a hose, watched a toothless old man start and talk about using a chainsaw, listened to two fellows in knit caps sitting in the shade talk about how to use a weather kit (they didn’t know how to measure wind speed), listened to a colorful character describe the proper way to use a shovel (you thought there was only one way, eh?), practiced deploying fire shelters in front of a trailer-mounted fan-boat there to simulate high winds, dug line with Pulaskis and McCleods, learned to use a radio, a map and a drip torch and finally, learned the ins and outs of fusees (giant emergency flares). We finished at 5. Dave and Eric from the Dino fire office showed up and livened things up a bit. We played frisbee and had a huge dinner. They served massive steaks but all they had was plasticware. Thus, everyone ended up eating the steaks like pizza boats. It was a grizzly sight. Most of the Canyon side crew went for a long walk at dusk. Upon our return, I sat and listened to Rowdy tell stories of firefighting in Alaska. As I mentioned earlier, he is a very colorful character. The night went quickly and the next morning the nice BIA man who had showed us how to use fire shelters walked through camp tapping tents and softly talking to wake people up. We were allowed an hour to pack up and eat breakfast (MREs) before loading up our gear and falling into our squads with full pack. Our packs consisted of basic survival suff: matches, water, compass, snacks, sunscreen, fire shelter, fusees and other odds and ends one wanted to take along for comfort. Everyone picked out a tool to dig line with. I grabbed a Pulaski, because I like saying it. We combined with another squad to make a 16-person crew, and hiked a half mile before starting to dig fire line straight uphill. I started out in front, hacking away and slowly moving upwards. The idea is to scrape away all vegetation down to mineral soil in an 18 inch swath, pulling vegetation away from the fire side. After 100 yards, the second guy in line took over the front position, which apparently is the hardest. Later, the guy third in line took over front position, and so on. It was excrutiatingly hot in the nomex pants, longsleeve shirt and hardhat with safety goggles. Very hard work. In the spirit of equal opportunity, I traded a guy tools and began using a combi, which is a sort of pick/hoe tool. It was hard work, but I was impressed at how quickly a 16-man crew could move along creating a nice clean fire line. I almost never stopped walking. At noon, we stopped and ate lunch, the fireline being finished around a very large perimeter. The line was actually in preparation for a controlled burn scheduled later in the summer. Turns out they never did it. After the noon-time MRE, we got a chance to really have fun, and work around an open fire in sagebrush. The organizers of the event tried their best to simulate a real fire situation, and even did a good job at acting panicked and shouting orders and getting us to trot along to the fire and such. We approached a large burning area, our tools in hand on the downhill side. The smoke blocked out the sky, and we began to dig when the crew boss told us to. We were scraping line much quicker than before. I suppose everyone’s adrenaline was up at the sight of real flame. In certain places our line was only a few feet from the flame. Smoke was everywhere, and my eyes watered and I coughed as I sucked in lungfulls of it. Before 15 minutes were up the line surrounded the fire and we relaxed. Then they drove an engine over to it and we all got in and started extinguishing hot spots by swirling them around while others sprayed water on the ground. That was it. Now I have a certificate that says I can fight fires. It wasn’t until mid-July

that I got to put that training to work. I was out at Haystack Rock with

Jim doing elk and deer pellet transects when a small puff of smoke appeared

to the NW and grew with tremendous speed into a 20 mile long column of

smoke stretching NE. I listened to the chatter on the radio from the fire

tower lookouts and learned it was over by Pot Creek, where I had done veg

monitoring in early June. Jim and I continued doing pellet transects all

day and the next. We returned back to HQ at 5 the next day when Steve contacted

me about going out to the fire. I was happy to. Janet Anderson, the part

time fire dispatcher, drove me out there along with dinners for the two

fire engine crews already there. We arrived at dusk, and David Hayes drove

back to HQ with Janet. David Pappadokus was on Engine 683 where I was assigned,

and two guys from Badlands NF, Mike Carlson and Chris, were on engine 682.

I had apparently missed the most dramatic run of the fire, where it had

burned over a thousand acres in a few hours, but the flames were still

burning bright. We sat in the engines parked on a ridge top a couple of

miles away and watched the flames torch pinyon pine and juniper on the

SW side of Offield Mt, just several hundred yards from the Lodore Canyon

rim. The fire was half on park land and half on BLM land. We watched until

10:30, then drove to the group of cabins nearby and slept out in the front

yard of the nicest one (the owner had welcomed us to use his cabin if we

liked). I slept by the glow of the fire to the east and a million stars

overhead. They called the fire Ecklund, and it cost millions. (See

a government page on the fire here)

After three days on the fire, we were pulled off and replaced by BLM engines. The fire continued to burn, under supervision, for weeks. Once it got going, it provided a great opportunity to clear out juniper and sagebrush intrusion into the range, so it was termed a natural prescribed fire, and allowed to burn within limits. Anywhere in the park one goes and sees a beautiful grassy meadow or a wildflower-filled valley is undoubtedly observing the product of fire. The absence of fire allows sagebrush, a fire-intolerant species, to dominate the landscape, and it looks ugly. Fire kills sagebrush, but not the perennial grasses, which come back in force the following spring along with annual flowers. The debate about sagebrush has never been settled since pre-European settlement altered the landscape in unknown ways. From my examination of the evidence, I have concluded the following: Solid sagebrush is not natural, and has only come about because of human fire suppression efforts. The grass is better forage for elk and cattle (though I’m not an advocate of cattle grazing on public land), looks nicer, is more diverse biologically and is the natural state of the range in this area. Because of low tourist numbers and its remoteness, Dinosaur is able to conduct controlled burns regularly without complaints, resulting in many areas where the sagebrush has been removed and replaced with tall green grass and brilliant flowers. The confounding factor of this is that cattle grazing is still allowed in parts of the park via grandfather grazing rights. Burned areas that are overgrazed immediately revert back to heavy sagebrush areas since cows eat the grass that comes up, allowing sagebrush to gain a foothold. Since cows won’t eat sagebrush, it takes over. Burned areas that were grazed are now sagebrush flats again, while burned areas that were not grazed are still grassland ten years later. The data don’t lie. Ranchers refuse to see this type of data for what it is, and would prefer to think that cattle grazing is beneficial for the ecosystem. This is simply not true in arid deserts. Fire is an excellent way to reverse decades of mismanagement by overgrazing.

After the Ecklund

fire was nearing exhasution, but still smoldering in the high elevation

Doug firs, plans began to shift to revegetation. A bigger burn called Buster

Flats had occurred right next to the Ecklund burn the year before, and

in fact was what stopped its northern progress now. This burn had also

been half on park land and half on BLM, and provided a good study area

of revegetation efforts since the BLM seeded and the park did not. So,

my job was to go in and collect data on ground cover inside the park and

outside the park within the burn perimeter. The exciting part was that

to get into the fire, we rode in a chopper. Kari, a volunteer working for

Tamara, the park botanist, went along while Jim, my usual fire-effects

partner worked for the Ecklund Fire Incident Management Team. We showed

up the night before we were to fly and camped out in a Ponderosa grove

near the canyon rim. The next day we got in the chopper at around Several days later,

it was determined that we needed more information on the revegetation efforts,

so Jim and I loaded a canoe onto our truck, and drove out to Lodore station

to paddle across the Green River and hike into the burn from the west.

The idea was a good one, but neither Jim nor I had the The final results,

statistically analyzed and well replicated, showed no difference in the

vegetation Later in September I worked on a different engine up at Lodore Ranger Station with a fellow from Smoky Mt NP name Mark. He was a very friendly guy and I liked working with him. We never got to fight any fires. We stayed at a bunkhouse near the ranger station, each morning we’d get up and spend an hour doing physical training our choice. I simply hiked up to the Gates of Lodore by the river, then jogged back on the rocky trail each day. David Hayes joined us after one day, and the three of us had a fun time, although we never got to get on a fire. We spent all day patrolling around, looking for smoke and waiting. Nothing came. My last trip in an engine was with two guys from Arkansas. They were crude, and only halfway friendly to me, resenting my inexperience and being stuck with someone who wasn’t a career firefighter. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the time we spent patrolling. We drove up towards, and then hiked to the top of, Tank’s Peak. There was an old cabin at the top of the peak, beaten down from years of wind. I couldn’t imagine spending a winter on top of that peak in that tiny cabin. Time ran out on me and my season ended September 21. There were few, if any, fires burning by then anyway. It was a very exciting experience, and a nice addition to my summer of fun. |

fire

as part of the way things are, as it is, the bearer of a clean start. I

also had the experience of hiking, or trying to hike, through snag-choked

forests that hadn’t burned in a century, where the forest floor was unseen

under several feet of logs, branches, and detritus, and the trees stood

like sick skeletons with all the lower limbs bare and black, shriveled

members on a massive bole shaded out and starved of sunlight past death.

I gradually came to like the idea of a big fire sweeping through and wiping

the forest clean. I visited areas that had burned and enjoyed the wide

open park-like stands of pine trees left behind, along with the profusion

of wildflower color always found on freshly burned soil. In comparison,

it was clear that an unburned forest is not natural, and is actually a

pretty dismal place to be. The trouble is, since the Forest Service has

been putting out fires as quick as possible for the last century, most

places haven’t had a chance to burn until the fuels have built up to where

any fire that does start isn’t content to be just a nice smoldering blaze

to cook off the undergrowth and fallen limbs, but instead quickly turns

into a roaring crown fire that takes out hundreds of years of growth all

at once. Thus enters the vision of forest fire that most people have: a

towering, out-of-control blaze that sweeps through the mountains like a

god of war, leaving nothing behind but a blackened landscape. We’ve brought

this on ourselves. Most forests in the west grew up with fires every few

years, and most forest trees are well adapted to resist low-scale fires

and some even require it to propagate the species. Aspen only grow in areas

cleared out by fire, and many pine tree cones only open after fire. But

no forest is adapted to infrequent burning, such as we have brought on

in our effort to protect a financial investment. The Forest Service for

many years treated its lands as giant farms to be tended and planted. Pesticides

and herbicides were used to control unwanted pests and fires were vigorously

suppressed to protect the standing timber for harvest. Once harvested,

only trees of value would be replanted, no soft firs or aspen would remain.

The lumber companies needed fine white pine, cedar and ponderosa for the

sawmill,

and that’s what they would get. Hard to believe? Comments on the master

plan can be found in letters and articles from the heads of the forest

service up into the 1970's, all available at any library. Not until the

environmental movement of the 1970's did the Forest Service think of the

forest as a natural ecosystem, with a fine balance of ecological factors

that kept it healthy and productive. Now the Forest Service has changed

its thinking quite a bit, but it is too late. Most areas are too choked

up to allow to burn without dire regional consequences, and many other

areas are so choked up with mountain retreats and summer cabins (gag) that

fire would burn up private property. For some reason, those living in the

mountains feel they deserve special protection from natural elements such

as fire, and will sue (have sued) the government for failing to put out

fires that eat up their cabins, even though fires have been a part of the

landscape since it was formed. Finally, the Forest Service is so busy putting

out catastrophic fires that have started as a result of years of fire suppression

and fuels buildup that there is very little money to conduct controlled

burns and clearing operations to reduce fuels to the point of eliminating

the prospect of a catastrophic crown fire. It is a vicious cycle with many

hindrances that will ultimately lead to the complete destruction of every

forest in the country. Thus, I am by now pro-fire, as long as it doesn’t

get out of control. I will elaborate on the ecological benefits of fire

later on.

fire

as part of the way things are, as it is, the bearer of a clean start. I

also had the experience of hiking, or trying to hike, through snag-choked

forests that hadn’t burned in a century, where the forest floor was unseen

under several feet of logs, branches, and detritus, and the trees stood

like sick skeletons with all the lower limbs bare and black, shriveled

members on a massive bole shaded out and starved of sunlight past death.

I gradually came to like the idea of a big fire sweeping through and wiping

the forest clean. I visited areas that had burned and enjoyed the wide

open park-like stands of pine trees left behind, along with the profusion

of wildflower color always found on freshly burned soil. In comparison,

it was clear that an unburned forest is not natural, and is actually a

pretty dismal place to be. The trouble is, since the Forest Service has

been putting out fires as quick as possible for the last century, most

places haven’t had a chance to burn until the fuels have built up to where

any fire that does start isn’t content to be just a nice smoldering blaze

to cook off the undergrowth and fallen limbs, but instead quickly turns

into a roaring crown fire that takes out hundreds of years of growth all

at once. Thus enters the vision of forest fire that most people have: a

towering, out-of-control blaze that sweeps through the mountains like a

god of war, leaving nothing behind but a blackened landscape. We’ve brought

this on ourselves. Most forests in the west grew up with fires every few

years, and most forest trees are well adapted to resist low-scale fires

and some even require it to propagate the species. Aspen only grow in areas

cleared out by fire, and many pine tree cones only open after fire. But

no forest is adapted to infrequent burning, such as we have brought on

in our effort to protect a financial investment. The Forest Service for

many years treated its lands as giant farms to be tended and planted. Pesticides

and herbicides were used to control unwanted pests and fires were vigorously

suppressed to protect the standing timber for harvest. Once harvested,

only trees of value would be replanted, no soft firs or aspen would remain.

The lumber companies needed fine white pine, cedar and ponderosa for the

sawmill,

and that’s what they would get. Hard to believe? Comments on the master

plan can be found in letters and articles from the heads of the forest

service up into the 1970's, all available at any library. Not until the

environmental movement of the 1970's did the Forest Service think of the

forest as a natural ecosystem, with a fine balance of ecological factors

that kept it healthy and productive. Now the Forest Service has changed

its thinking quite a bit, but it is too late. Most areas are too choked

up to allow to burn without dire regional consequences, and many other

areas are so choked up with mountain retreats and summer cabins (gag) that

fire would burn up private property. For some reason, those living in the

mountains feel they deserve special protection from natural elements such

as fire, and will sue (have sued) the government for failing to put out

fires that eat up their cabins, even though fires have been a part of the

landscape since it was formed. Finally, the Forest Service is so busy putting

out catastrophic fires that have started as a result of years of fire suppression

and fuels buildup that there is very little money to conduct controlled

burns and clearing operations to reduce fuels to the point of eliminating

the prospect of a catastrophic crown fire. It is a vicious cycle with many

hindrances that will ultimately lead to the complete destruction of every

forest in the country. Thus, I am by now pro-fire, as long as it doesn’t

get out of control. I will elaborate on the ecological benefits of fire

later on.

The

following few days we spent near the cabins, officially posted for structure

protection in case the fire turned this way, but it never did. Steady SW

winds never let up. We kept an eye on the fire front and took weather reports

every hour. In the meantime we played Euchre under the outdoor patio covering

of the cabin and read novels, played frisbee and hiked around the rocky

hills. We also explored the old abandoned cabins nearby and marveled that

people could ever live this far out of the way without cars. Yes, this

seems like a waste of time and money. But just think if the fire turned

the other way and burned up the cabins and there wasn’t any firefighter

around to at least make a show of trying to save the structures. Don’t

think the owners wouldn’t sue the government in a heartbeat and collect

quadruple what their cabins were worth. That’s our legal system. People

do this all the time. They figure if the government didn’t save their forest-surrounded

structures, there was negligence somewhere along the line. Never mind that

most of them had received the land for free from the government through

homesteading acts. Never mind that most fires are started by lightening.

The

following few days we spent near the cabins, officially posted for structure

protection in case the fire turned this way, but it never did. Steady SW

winds never let up. We kept an eye on the fire front and took weather reports

every hour. In the meantime we played Euchre under the outdoor patio covering

of the cabin and read novels, played frisbee and hiked around the rocky

hills. We also explored the old abandoned cabins nearby and marveled that

people could ever live this far out of the way without cars. Yes, this

seems like a waste of time and money. But just think if the fire turned

the other way and burned up the cabins and there wasn’t any firefighter

around to at least make a show of trying to save the structures. Don’t

think the owners wouldn’t sue the government in a heartbeat and collect

quadruple what their cabins were worth. That’s our legal system. People

do this all the time. They figure if the government didn’t save their forest-surrounded

structures, there was negligence somewhere along the line. Never mind that

most of them had received the land for free from the government through

homesteading acts. Never mind that most fires are started by lightening.  That’s

the way it is. On this particular occasion, I was complaining less than

most since I was making a lot of money for easy work, but then again, I

didn’t know it would be easy when I volunteered. It could have just as

well been 16 hours a day of digging line and cutting shrubs. Just worked

out that it wasn’t. Hotshot crews from Tutanka and Bitterroot showed up

and performed the actual line digging. Helicopters dropped water and tankers

dropped retardant. It was quite a spectacle. At night we all camped together

in a spike camp in a grassy field with air-delivery of food and supplies.

That’s

the way it is. On this particular occasion, I was complaining less than

most since I was making a lot of money for easy work, but then again, I

didn’t know it would be easy when I volunteered. It could have just as

well been 16 hours a day of digging line and cutting shrubs. Just worked

out that it wasn’t. Hotshot crews from Tutanka and Bitterroot showed up

and performed the actual line digging. Helicopters dropped water and tankers

dropped retardant. It was quite a spectacle. At night we all camped together

in a spike camp in a grassy field with air-delivery of food and supplies.

Only

5 days after being taken off that fire, a thunderstorm rolled through and

started a fire near Turner Creek, just south of the park. I rode with David

Pappadokus on Engine 682 and we were the first to arrive. I shot water

at the fire while he drove the engine. We started at the ignition point

and worked up the flank, while the second engine to arrive with a guy from

MT and another from Rocky Mt NP worked the other flank. The fire burned

up a hill and the slope got too steep for us. A retardant drop was called

in, and soon a single-engine red plane was laying down a line of red slurry

at the hilltop. I was amazed at how this single act virtually stopped the

fire altogether. It lost all momentum and calmed down to a small snaking

fire. A BLM engine was dispatched to contain the flame at the hilltop.

The other park engine left to draft water from a nearby pond. Dave drove

the engine around the perimeter while I sprayed water on hot spots. We

left, and drove around up top of the hill to give the BLM crew a hand.

It was well past dark by then, and by the light of headlamps, we sprayed

water on the flames

Only

5 days after being taken off that fire, a thunderstorm rolled through and

started a fire near Turner Creek, just south of the park. I rode with David

Pappadokus on Engine 682 and we were the first to arrive. I shot water

at the fire while he drove the engine. We started at the ignition point

and worked up the flank, while the second engine to arrive with a guy from

MT and another from Rocky Mt NP worked the other flank. The fire burned

up a hill and the slope got too steep for us. A retardant drop was called

in, and soon a single-engine red plane was laying down a line of red slurry

at the hilltop. I was amazed at how this single act virtually stopped the

fire altogether. It lost all momentum and calmed down to a small snaking

fire. A BLM engine was dispatched to contain the flame at the hilltop.

The other park engine left to draft water from a nearby pond. Dave drove

the engine around the perimeter while I sprayed water on hot spots. We

left, and drove around up top of the hill to give the BLM crew a hand.

It was well past dark by then, and by the light of headlamps, we sprayed

water on the flames  and

used shovels to churn in the hot spots. It wasn’t until after midnight

when we started to leave, and promptly blew out a tire. We changed that,

and headed to HQ. The next morning we left at 6 to go back out and mop

up. We took turns carrying the 15 gallon “piss-pump” while the other carried

the rhino and churned up the hot spots for the water to get in. That took

all morning. The fire was officially out by 12. I was dirty and very tired

by the end, but it was, I have to admit, great fun. Anytime one is paid

to work outdoors in beautiful country, he can't complain.

and

used shovels to churn in the hot spots. It wasn’t until after midnight

when we started to leave, and promptly blew out a tire. We changed that,

and headed to HQ. The next morning we left at 6 to go back out and mop

up. We took turns carrying the 15 gallon “piss-pump” while the other carried

the rhino and churned up the hot spots for the water to get in. That took

all morning. The fire was officially out by 12. I was dirty and very tired

by the end, but it was, I have to admit, great fun. Anytime one is paid

to work outdoors in beautiful country, he can't complain.

10

and were dropped off in the burn. The pilot was nice, but the helittack

guy with him was a cocky, rude little punk. The heat of the day caused

vicious thermals, and the helicopter rose and fell like a boat in a seastorm.

I quickly began to feel woozy, and frantically willed the chopper to set

us down quickly on the ground. I had decided that since there was nothing

else not strapped down in the passenger compartment that I would take off

my helmet and use that as an airsick bag if it came to it. The pilot would

sure be sore if I puked on his chopper floor, I’m sure. Fortunately, it

never came to that. Kari and I were left in the old burn, and we set out

to gather several transects of data in and out of the burn. The terrain

was blackened, moonscaped and eerie. Only a few plants grew among the skeleton

pinyon pines, notabley huge sunflowers. We were set down in a deep draw,

with steep loose rock walls on both sides. It was tough going over the

deep sand and large rocks. The helicopter returned in three hours and ferried

us back to the spike camp.

10

and were dropped off in the burn. The pilot was nice, but the helittack

guy with him was a cocky, rude little punk. The heat of the day caused

vicious thermals, and the helicopter rose and fell like a boat in a seastorm.

I quickly began to feel woozy, and frantically willed the chopper to set

us down quickly on the ground. I had decided that since there was nothing

else not strapped down in the passenger compartment that I would take off

my helmet and use that as an airsick bag if it came to it. The pilot would

sure be sore if I puked on his chopper floor, I’m sure. Fortunately, it

never came to that. Kari and I were left in the old burn, and we set out

to gather several transects of data in and out of the burn. The terrain

was blackened, moonscaped and eerie. Only a few plants grew among the skeleton

pinyon pines, notabley huge sunflowers. We were set down in a deep draw,

with steep loose rock walls on both sides. It was tough going over the

deep sand and large rocks. The helicopter returned in three hours and ferried

us back to the spike camp.

faintest

idea how to navigate a canoe on swift water, so we foundered, and spun

the canoe around here and there, and generally made a great spectacle in

front of rafters issuing from the same boat ramp. Finally, we managed to

get straightened out and headed upstream. Only a little ways up, we landed

the canoe on the opposite bank and got out to hike uphill to the burn.

This was done and we got lots of new information. Back on the river, we

paddled up until the sky darkened and lightening hit the distant mountains.

Fearing water’s conductivity, we beached the canoe and hiked in to find

the remaining deer and elk pellet group transects in the area. We got to

these and collected the data, then enjoyed a nice canoe ride downstream

to the boat ramp. We ended up spending around 16 hours that day at work.

faintest

idea how to navigate a canoe on swift water, so we foundered, and spun

the canoe around here and there, and generally made a great spectacle in

front of rafters issuing from the same boat ramp. Finally, we managed to

get straightened out and headed upstream. Only a little ways up, we landed

the canoe on the opposite bank and got out to hike uphill to the burn.

This was done and we got lots of new information. Back on the river, we

paddled up until the sky darkened and lightening hit the distant mountains.

Fearing water’s conductivity, we beached the canoe and hiked in to find

the remaining deer and elk pellet group transects in the area. We got to

these and collected the data, then enjoyed a nice canoe ride downstream

to the boat ramp. We ended up spending around 16 hours that day at work.

cover

of seeded and unseeded burned areas. Given the enormous cost of reseeding

(3 lbs seed/acre at $9/lb) it is just not justified to reseed this area.

I hope they took this information into account and did not spend any money

trying to seed the Ecklund burn, but I left before finding out what happened

with that.

cover

of seeded and unseeded burned areas. Given the enormous cost of reseeding

(3 lbs seed/acre at $9/lb) it is just not justified to reseed this area.

I hope they took this information into account and did not spend any money

trying to seed the Ecklund burn, but I left before finding out what happened

with that.