| Down

the River

Green River Trip: Gates of Lodore to Split Mountain

By the time we got

to the boat ramp it was nearing lunch, so we had a nice meal of Melissa’s

homemade humus with fresh, raw veggies. The river was clear and low. I

watched an osprey catch a trout thirty feet in front of me as I sat near

the calm river. They weren’t letting much water This trip was the

second to last of the season, and on it we were not meeting big groups

of volunteers as Jeremy and Melissa typically had all summer. Instead,

this was a trip that we could enjoy, while performing a valuable public

service, of course, within the confines of our small group. We had put

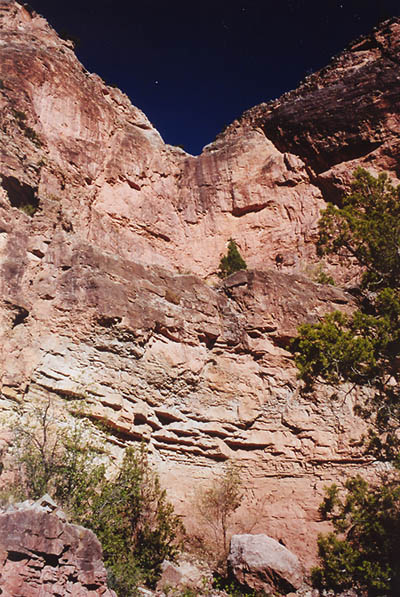

in just upstream from the Gates of Lodore, a melodramatic name for a very

dramatic spectacle. On a map, the contour lines for the canyon walls overlap

for more than 1500 feet. Here is where a flat wide river is pressed in

between giant drab walls several hundred feet high at the lowest, and remains

hidden and almost inaccessible for the next 44 miles. I pictured Back in the water and downstream, through rapids and a day of fun on the river. We passed by the smoldering remains of Ecklund Draw (where I had spent a week on a fire engine watching a fire burn), Upper and Lower Disaster Falls (so named because it was where one of Powell’s rafts broke up), my previous closest descent to Lodore Canyon at Pot Creek, and a few bighorn sheep curiously watching our big blue rafts glide by on the surface of the water. I don’t know where we camped that evening. It was a very nice beach somewhere on the left bank, with deep white sand rolling back into willows and tamarisk. We had a nice dinner and sat in canvas chairs until the darkness in the canyon grew complete and the sky was a silver-dusted strip up above between black canyon walls. Carrie and I slept on the beach, while Jeremy and Melissa slept in their boats moored to the beach. I took great effort to dig a well-fitted hip and shoulder bowl in the sand before I laid my foam sleeping bad down on the beach. Very comfortable..better than a sleep number bed. Several times as I was drifting off to sleep, trying to take in as much of the stars and beauty as I could, the pattern of the waves would form a rhythm that almost sounded like someone walking in the water just off shore. Of course, no one was. The cool air swept down the canyon in a soft breeze and I slept fantastically. The next day we had

to do some more digging and cutting and spent quite awhile at this labor.

The tamarisk germinate, then years of sand is deposited on them so that

the original soil level that the roots sprouted into is several feet under.

Thus, digging down to the taproot is required to cut and kill the things.

Some of the tamarisk trees form thickets and it becomes necessary to trim

several dozen long shoots from the base just to get working room. Often,

several trees grow together, and it is a great puzzle which way each trunk

snakes up through the sand. It is also often difficult to tell where the

tap root begins. Jeremy and Melissa were, of course, very keen at spotting

and predicting these things. I just dug where they instructed to. In the

sun, in the canyon, in the sand, it is hard work. But I still prefer it

to desk work. Settlers brought tamarisk here on purpose just so 150 years

later four bodies could find a reason to justify a river trip. This beach,

like others, had been worked over most of the summer and we were there

mainly to clean up small pieces left behind before they rooted, to finish

the few remaining stumps not yet fully unearthed and to pile everything

up nice and neat to slowly cook and die in the sun overwinter. Tossing

the After hours of that, we hopped in the boats and took off down the river. What a nice feeling it is to be going downriver when you have little idea what lay ahead. Jeremy let me row the boat for awhile, and I quickly discovered that rowing is much, much harder than it is made to look by an experienced rower. I strained and pulled, but my heroic struggles seemed to not be doing much at all. We approached Triplet Falls and Melissa went down first. I watched her go through alright, making it look easy, then Jeremy instructed me on how I should row to get through. He shouted several things above the din of the rapids, but no matter how hard I tried to follow the instructions, I couldn’t. My oars were defective, I think. The current was too strong,and I got us beached on a flat rock in the middle of the river up above the current. Jeremy hopped out on the rock and pushed to get us going again. Thus ended my stint as a rower. Everyone had a good laugh. We stopped for lunch just then on a nice little beach, then went on down the river some more.

We rode over the largest rapids of the river at Hell’s Half Mile, class III or IV, I don’t recall which, but probably class III since it was low water. We stopped at Rippling Brook and hiked up to a waterfall in a cool, dark, sandstone alcove some twenty five feet high and same across, hidden from outside view by large Douglas Fir (which is neither a fir, nor a hemolck, as implied by its latin name, Psuedotsuga). A thin spray of water fell over the ledge far above and splattered on the rock below, spraying in all directions. It was possible, I was told, to hike around to the top of the falls and look down. I would have liked to, but there was not enough time. Always on this trip, not enough time. Our second camp was

once again some nameless beach on the left side of the river. Before we

even stopped, there was talk of taking a swim, since the afternoon had

been clear and hot. Let me say again that the water was very cold. We beached

the boats and it was still hot in the shade on the beach and I thought

it sounded good. I waded out into the water up to my ankles, and instantly

felt very cold up to the hair follicles on my head. The right canyon wall

cast a deep shadow on our beach, but I spotted sunlit-beach several dozen

yards down and around a bend, so I went down there. I began to wade in

the cold water, tempered by the hot sun on my chest, when I heard a splash,

then a scream. Commotion up river. Jeremy came charging through the water

toward me, or rather, toward sunlight, dripping with water and holding

his hands in clenched fists and laughing. He too had noted that the sunshine

was only downstream, a fact that became apparent when he jumped into the

icy water. He got into the sun and seemed to feel less hypothermic. I went

out into the current and kicked out my legs from under me, instantly plunging

myself completely underwater. I came up and gasped and realized what it

is like to be so cold you can’t think or breath. I panicked for an instant,

then charged out of the water, gasping and red. Such cold water for such

a hot place!

Back at camp we ate

dinner by the river shore on the sandy beach. The setup they had for dinner

was pretty nice. Folding table and chairs, a Coleman stove, dishwashing

basins, a dish-dry bag and recycling bags for cans tied to the table legs,

and an array of compact flatware. We ate very elaborate meals. That night

it was cheese and spinach quesadillas with black beans and salsa. In the

river canyon, of course, everything must be packed out. There were unique

leave no trace practices that I found surprisingly rigid. For example,

food particles could not be disposed of in the river (crumbs, bits of beans

left in the pot, etc.) and had to be filtered out and stored in a bucket

to be added to the compost bin back at the office. Peeing always took place

directly into the river. “Dilute, don’t pollute”. Other bodily functions

took place in a portable toilet called the “Groover”. Acording to Jeremy,

the name comes from early rafting days when army ammo cans were used for

this purpose. After sitting on an ammo can for several minutes, one had

deep grooves imprinted in the flesh of the bum and legs, hence the name.

I rarely failed to find humor in the name as it invoked an image of some

sort of righteous party dude, living it up. The groover was always set

up in some scenic location away from camp, behind a willow thicket or something,

with a nice view of the mountains or the river to admire while taking care

of business. The handwashing The following day we spent all morning digging tamarisk, and unearthed some champion-sized weeds. It was sobering to realize how much work it took to pull one tree out, and then see dozens of beaches along the river downstream completely choked with them. Near Echo Park, the tamarisk is so thick you can’t even beach a boat in many places. You can’t even walk to the river from the campground, unless you’re a mouse. The entire Colorado River watershed is infested with tamarisk, and it comes up so fast from seed that constant attention must be paid to beaches to ensure they aren’t taken over in a few years. The only hope of ultimate control is in biocontrol. One promising species comes in the form of a beatle being tested in TX that likes to eat tamarisk. It seems to work pretty well, but now the holdup is that tamarisk has replaced willow habitat for an endangered species of bird in Arizona. Birders fear that reducing tamarisk will kill off this bird. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. The rafting that

day took us past Steamboat Rock and Echo Park, where I had camped just

a couple of weeks earlier. This is where the Yampa meets up with the Green.

Echo Park was named by John Powell in 1869, but was first visited by fur

trappers in 1825. I marvel at the ability of fur trappers to have gotten

so far down into the canyons way back in 1825. The name is fitting, since

in every direction there are stone walls curving this way and that, all

at least a thousand feet high. The water in this area was deep and slow

and required lots of rowing to keep going downriver, so consequently, it

is very quiet here too. Every word echoes. The first person to live in

the area was a hermit named Patrick Lynch, who moved west after a stretch

as a Union naval captain in the Civil War. He said he wanted to get as

far away from the ocean as possible, and gradually settled down in the

network of canyons and caves around Echo Park (1500 miles from the Pacific).

He lived off of jerkied meat from cows that washed down river in the spring

floods and had a network Our tiny flotilla of rubber and plastic stopped just inside Whirlpool Canyon to have lunch on the nicest, largest beach yet. Because of the time of day, it was completely in shade (mercifully). It stretched about 50 feet back to the rock wall, where after lunch Jeremy and Melissa tried to solve a climbing problem on an overhang. Melissa pointed out ladders high up in the walls, abandoned over thirty years ago when environmental groups blocked construction of two dams in this canyon. That was the first big victory for the Sierra Club. If not for a few concerned individuals decades ago, the beach we stood on would be drowned under 500 feet of murky, stagnant water, and Dinosaur National Monument would be a “National Recreation Area” with bathtub rings on the canyon walls just like Lake Powell. I did some exploring of my own along the beach and found an inexplicible steel pipe, 2" diameter, jutting out from the wall about a foot. I also found a thin chute that led up and up at a steep slope, but harboring trees that I used for leverage to twist my way up. I got up as high as I dared in the cool crevice, enjoyed the complete silence and isolation for a few moments, then slipped back down the tallus, slowing my descent by smooth handoffs from tree to tree. Everywhere I went, there were no human footprints in the sand.

Our camp for the

night was at the exit of the river from Whirlpool Canyon at a place called

The Cove. Here we saw the first people in three days, an elderly man and

woman fishing on the opposite bank. Jeremy, Melissa and I again went hiking,

while Carrie stayed at the beach and read. We bushwhacked up a steep rock

incline that got steeper all the time. Jeremy disappeared into a slot canyon

that led up so steeply I didn’t even consider following. My route diminished

in comfort to the point where I turned back. Melissa went on up ahead,

holding onto the slope that was almost vertical with hands and feet. I

used shrubs to help lower myself down, after which I struck off in a new

direction, across the draw and up a sandy hill. I had to circle it 180

degrees to find a path to the top through the loose dirt and rocks. This

hill is clearly visible on the map near the campground. I found a footpath

at the summit and trotted back to camp. I walked up the river into the

canyon as far as was feasible without swimming for it. I found an unopened

can of Diet Coke lyng in the rocks by the current, bleached almost beyond

recognition by sun and water. Some relic of a river trip, years ago. How

long? Perhaps someone wiped out and lost their drinks in the river. How

long does it take for a non-floating can of pop to wash down the river

to beach outside the canyon? I walked back to camp and grabbed my book

and found a nice sandy shallow enclosed on three sides by juniper to relax

in. The opening to my little room faced the beach, although the view was It was hot, so we all took a nice swim in the water, which was warmer than the day before owing to the extra 35 miles of solar charging. We also noticed that the water was muddy and brown, probably an effect from a surge of water being released from the dam. After that, we ate dinner on the beach, as always, just a few feet from the water. We stayed up much later that night, enjoying the last night on the river. Jeremy espoused his theory on how cloning would save the world by destroying the human race. Other topics were equally intellectual. The canyon was behind us, and the whole open sky of stars was open above us. By bedtime, the only lights were the soft glow of the stars, and the glow from Jeremy’s hand rolled cigarette. Crickets formed the tenor voice to complement the ever present river-ripple bass. I slept under the arch of a willow thicket on the sand, twenty feet from water. The next morning I discovered mouse tracks completely circling me and, tracing their paths, found they went up and over my bag. The last day of the trip led us through flat river areas where the surrounding terrain was flat and dry. We cruised through Island Park, and saw a bald eagle and a huge black bull moose. The moose was especially out of place since ten feet from the river lay nothing but sagebrush and cactus. He must be looking for a way out. The late summer dryness had sucked all the green out of the surrounding hills and flats, and it looked desolate. We passed by Ruple Ranch and Rainbow Park, where I had burned and sweated under the sun doing veg monitoring way back in June. It was poignant to remember back to the carefree days of early summer spent just beside the river, now to see that place again with the end of summer in sight. We entered Split

Mountain Canyon, and had a few last big thrills on Moonshine and Warm Springs

rapids before coasting on in to the takeout at Split Mountain. I don't

have any photographs of any of the rapids we coasted over on the trip because

I tucked my camera into

|

The

inflatable rafts were the last thing onto the boat trailer, and it took

5 people to get them on. Jeremy stood on the back of the trailer and pulled

on the front as four of us on the ground walked one out of the river cache

and threw it up to him. Then we did it again with another boat. It was

early morning, Sept 9 2001. We loaded the truck under a depthless blue

disc, cloudless, arid. A desert sky. Soon, all was ready. The truck was

carrying enough food and water for 4 people for 4 days, perhaps longer.

Shovels and clippers were stashed in canvas bags under the rafts, tools

we would use for tamarisk removal on the river. Melissa and Jeremy were

the seasonal employees of the park service in charge of this trip. They

were “weed warriors”, group leaders who coordinated the efforts of volunteers

in the task and ultimate goal of complete tamarisk eradication from certain

beaches that lined the banks of the Green River within Dinosaur National

Monument. They were also pretty good river runners, and had spent all summer

paddling down the Green River and its undamed tributary, the Yampa.

The

inflatable rafts were the last thing onto the boat trailer, and it took

5 people to get them on. Jeremy stood on the back of the trailer and pulled

on the front as four of us on the ground walked one out of the river cache

and threw it up to him. Then we did it again with another boat. It was

early morning, Sept 9 2001. We loaded the truck under a depthless blue

disc, cloudless, arid. A desert sky. Soon, all was ready. The truck was

carrying enough food and water for 4 people for 4 days, perhaps longer.

Shovels and clippers were stashed in canvas bags under the rafts, tools

we would use for tamarisk removal on the river. Melissa and Jeremy were

the seasonal employees of the park service in charge of this trip. They

were “weed warriors”, group leaders who coordinated the efforts of volunteers

in the task and ultimate goal of complete tamarisk eradication from certain

beaches that lined the banks of the Green River within Dinosaur National

Monument. They were also pretty good river runners, and had spent all summer

paddling down the Green River and its undamed tributary, the Yampa.

out

this time of year from the dam at Flaming Gorge (Flaming George). Snowmelt

from the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming runs into this mammoth pool of

still water and sits until farmers need it for irrigation, or Pheonix decides

they need more water to fill their swimming pools. The water in the reservoir

is deep and becomes clear as the sediment settles out. For us this also

meant the water was very cold, even after a hot summer, since they let

the water out of the bottom of the reservoir where the sun never shines.The

packing of the boats took longer than I expected, owing to the hundred

and one boxes and bags required for the trip. Jeremy and Melissa seem like

free-wheeling carefree kind of folks, but in packing they were as meticulous

as engineers. We hopped in the boats at last and shoved off onto the slick

water. I rode in the front of Jeremy’s raft since Carrie was an old friend

of Melissa’s from Arizona and they wanted to catch up. I was also a seasonal

employee at Dinosaur, but my duties had kept me high and dry on the river

benches a thousand feet up,where the rattlesnakes live. It was a great

job, but I was happy for the chance to raft a big river and to get down

in the canyons I had looked down on for the last 3 months.

out

this time of year from the dam at Flaming Gorge (Flaming George). Snowmelt

from the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming runs into this mammoth pool of

still water and sits until farmers need it for irrigation, or Pheonix decides

they need more water to fill their swimming pools. The water in the reservoir

is deep and becomes clear as the sediment settles out. For us this also

meant the water was very cold, even after a hot summer, since they let

the water out of the bottom of the reservoir where the sun never shines.The

packing of the boats took longer than I expected, owing to the hundred

and one boxes and bags required for the trip. Jeremy and Melissa seem like

free-wheeling carefree kind of folks, but in packing they were as meticulous

as engineers. We hopped in the boats at last and shoved off onto the slick

water. I rode in the front of Jeremy’s raft since Carrie was an old friend

of Melissa’s from Arizona and they wanted to catch up. I was also a seasonal

employee at Dinosaur, but my duties had kept me high and dry on the river

benches a thousand feet up,where the rattlesnakes live. It was a great

job, but I was happy for the chance to raft a big river and to get down

in the canyons I had looked down on for the last 3 months.

John

Wesley Powell guiding his flotilla into this canyon, with 10 times the

water rushing on the then-undamned river, not knowing when or where he

would be able to get out. Now that’s adventure. Jeremy and Melissa could

definitely tell a much more detailed story of the river’s history than

I, and if you ever meet them, be sure to ask. As the water entered the

canyon, we sped up and encountered little ripples here and there. Before

we hit any major rapids at all, we beached the rafts at Winnie’s Grotto

and got out to work. For about an hour, we dug up tamarisk and cut roots.This

was mostly cleanup since they had groups working there all summer. Most

of the tamarisk were already gone and the beach looked very nice.

John

Wesley Powell guiding his flotilla into this canyon, with 10 times the

water rushing on the then-undamned river, not knowing when or where he

would be able to get out. Now that’s adventure. Jeremy and Melissa could

definitely tell a much more detailed story of the river’s history than

I, and if you ever meet them, be sure to ask. As the water entered the

canyon, we sped up and encountered little ripples here and there. Before

we hit any major rapids at all, we beached the rafts at Winnie’s Grotto

and got out to work. For about an hour, we dug up tamarisk and cut roots.This

was mostly cleanup since they had groups working there all summer. Most

of the tamarisk were already gone and the beach looked very nice.

cut

branches into the water would only take them down river a few miles where

they would beach and root and form new thickets. One must let them cure

for a year on shore before dumping them in the current.

cut

branches into the water would only take them down river a few miles where

they would beach and root and form new thickets. One must let them cure

for a year on shore before dumping them in the current.

Our

rafts swept swiftly past dozens of little side chutes and crevices, shady

groves of willows with hidden rock passages behind I’m sure. I watched

with regret the dozens of perfect shimmering beaches we were passing by,

probably all of which I’ll never see again. One could easily spend a couple

of weeks, perhaps years, on the river, taking it slow and exploring everything

thoroughly.

Our

rafts swept swiftly past dozens of little side chutes and crevices, shady

groves of willows with hidden rock passages behind I’m sure. I watched

with regret the dozens of perfect shimmering beaches we were passing by,

probably all of which I’ll never see again. One could easily spend a couple

of weeks, perhaps years, on the river, taking it slow and exploring everything

thoroughly.

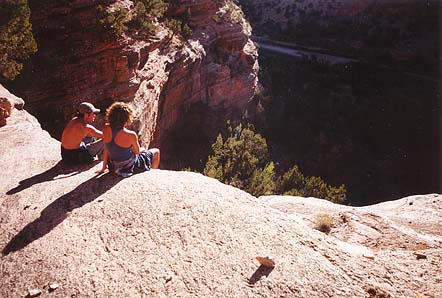

Immediately

following this, Jeremy, Melissa and I hiked up behind the beach toward

the rock wall of the canyon set far back from the water in this area on

the left bank. We scrambled up tallus slopes and zig-zagged around to a

dry wash of solid rock molded smooth as glass by millennia of downpours.

I was impressed how Jeremy could scramble up tallus slopes holding a beer

in his hand. The sun still shone up there, and the warmth after the swim

was tantalizing. We were dry in minutes. The rock was deep yellow, and

the needles on the pinyon pines were brilliant green in front of it. We

reached a flat rock ledge that dropped off to the wash 25 or 50 feet below

and sat and watched the river gliding imperceptibly along. (Does the river

glide or is it only the water which does so...or is it the same?) Jeremy

and Melissa decided to continue up. The way was steep and I decided to

hang around the flat place. Several minutes later, Jeremy called down from

a boulder directly overhead telling me I had to see the view. Well, if

you say so...So I went on up, pulling myself up the steep, rocky wall by

grabbing onto tree trunks and branches, trying to forget that I have no

health insurance. I made it to the top and felt so sure of slipping off

to the

Immediately

following this, Jeremy, Melissa and I hiked up behind the beach toward

the rock wall of the canyon set far back from the water in this area on

the left bank. We scrambled up tallus slopes and zig-zagged around to a

dry wash of solid rock molded smooth as glass by millennia of downpours.

I was impressed how Jeremy could scramble up tallus slopes holding a beer

in his hand. The sun still shone up there, and the warmth after the swim

was tantalizing. We were dry in minutes. The rock was deep yellow, and

the needles on the pinyon pines were brilliant green in front of it. We

reached a flat rock ledge that dropped off to the wash 25 or 50 feet below

and sat and watched the river gliding imperceptibly along. (Does the river

glide or is it only the water which does so...or is it the same?) Jeremy

and Melissa decided to continue up. The way was steep and I decided to

hang around the flat place. Several minutes later, Jeremy called down from

a boulder directly overhead telling me I had to see the view. Well, if

you say so...So I went on up, pulling myself up the steep, rocky wall by

grabbing onto tree trunks and branches, trying to forget that I have no

health insurance. I made it to the top and felt so sure of slipping off

to the  rocks

below I couldn’t bring myself to stand up straight for more than a few

seconds. I took some photos and I recall Jeremy predicting that the shot

up canyon would win the Nobel Peace Price. I’m still waiting on that particular

accolade.

rocks

below I couldn’t bring myself to stand up straight for more than a few

seconds. I took some photos and I recall Jeremy predicting that the shot

up canyon would win the Nobel Peace Price. I’m still waiting on that particular

accolade.

station

was near camp, and consisted of a bucket with a foot pump that expelled

bleach water out of a thin tap into another empty bucket. On top of the

bleach water bucket was a sign weighted by a rubber Stegosaurus that said

“Banio Occupano” that one was supposed to place erect on the way to the

scenic outhouse to avoid embarrassing encounters.

station

was near camp, and consisted of a bucket with a foot pump that expelled

bleach water out of a thin tap into another empty bucket. On top of the

bleach water bucket was a sign weighted by a rubber Stegosaurus that said

“Banio Occupano” that one was supposed to place erect on the way to the

scenic outhouse to avoid embarrassing encounters.

of

caves he lived in, most labeled with his sign, which was a capital P with

an L bottom on it. Steve told us these are still found carved in the sandstone

walls of Echo Park here and there, if you know where to look. My friend

Dave and I located what appeared to be one of his old caves just a week

before.

of

caves he lived in, most labeled with his sign, which was a capital P with

an L bottom on it. Steve told us these are still found carved in the sandstone

walls of Echo Park here and there, if you know where to look. My friend

Dave and I located what appeared to be one of his old caves just a week

before.

We

continued on under an unbroken blue sky, passing Jones Hole where I had

swum in the river and seen a magnificently-sized trout picking at rocks

a week before with Dave. The clear, cold water emerging from Jone’s Hole

Creek kept to itself for some distance down the river, forming a clear

band of water within the relative muddiness of the river.

We

continued on under an unbroken blue sky, passing Jones Hole where I had

swum in the river and seen a magnificently-sized trout picking at rocks

a week before with Dave. The clear, cold water emerging from Jone’s Hole

Creek kept to itself for some distance down the river, forming a clear

band of water within the relative muddiness of the river.

interrupted

by willows and tamarisk. I heard Jeremy and Melissa hiking back, talking

quietly in the orange evening sun. They walked just past my little room

and stopped about 10 feet in front, looking at the beach, their backs to

me. Jeremy whispered furtively and grinned a toothy smile, and I knew what

he was up to. He found a rock and was craning his neck over the junipers

to find Carrie and I, presumably sitting on the beach. Just as he pulled

back his arm to let fly, I smacked the ground at his feet with a large

rock I had silently hurled from the shadows. A look of utter surprise with

wide eyes came over his face as he jerked back and looked wildly around.

Then he saw me in the shadows and laughed. You got to get up pretty early

in the morning to pull one over on me.

interrupted

by willows and tamarisk. I heard Jeremy and Melissa hiking back, talking

quietly in the orange evening sun. They walked just past my little room

and stopped about 10 feet in front, looking at the beach, their backs to

me. Jeremy whispered furtively and grinned a toothy smile, and I knew what

he was up to. He found a rock and was craning his neck over the junipers

to find Carrie and I, presumably sitting on the beach. Just as he pulled

back his arm to let fly, I smacked the ground at his feet with a large

rock I had silently hurled from the shadows. A look of utter surprise with

wide eyes came over his face as he jerked back and looked wildly around.

Then he saw me in the shadows and laughed. You got to get up pretty early

in the morning to pull one over on me.

the

dry box whenever I heard the roar of whitewater up ahead. We pulled the

boats up to the empty concrete ramp and beached them. Then we ate lunch

in the shade and unloaded all the gear from the rafts and stacked it on

the ramp. We sat in the shade and waited for Vanessa to pick us up in the

trailer. Someone commented on how odd it was to be returning to “civilization”after

so long out of contact. Jeremy told a story of how the usual pickup guy

would always come up with some bullshit story to tell people just getting

off the river, such as “Well, we declared war on Canada while you was gone,”or

some other such nonsense. Thus it was that none of us took Vanessa seriously

when she told us that the World Trade Center towers had been destroyed

by airline jets the day before. I mean, how ridiculous does that sound?

We didn’t believe her, despite her serious attempts otherwise, until we

stopped at the Sinclair in Jenson for shakes and saw the TV sets replaying

the disaster again and again. I figured that at about the time it happened,

we were busy digging up tamarisk on a sandy, shady beach without a care

in the world. A very strange thought, that. We emerged from that bliss

of ignorance to a whole different animal. And I’d have to say that not

seeing another person outside our group for 4 days was the best part of

the whole experience. Even great places lose their charm when you’ve got

to share them with other bipeds. Anyway, that’s how the trip ended, the

trip of a lifetime, really. It was a fantastic ending to my summer at Dinosaur.

I packed up and left for home one week later and I’ve been dreaming of

going back ever since.

the

dry box whenever I heard the roar of whitewater up ahead. We pulled the

boats up to the empty concrete ramp and beached them. Then we ate lunch

in the shade and unloaded all the gear from the rafts and stacked it on

the ramp. We sat in the shade and waited for Vanessa to pick us up in the

trailer. Someone commented on how odd it was to be returning to “civilization”after

so long out of contact. Jeremy told a story of how the usual pickup guy

would always come up with some bullshit story to tell people just getting

off the river, such as “Well, we declared war on Canada while you was gone,”or

some other such nonsense. Thus it was that none of us took Vanessa seriously

when she told us that the World Trade Center towers had been destroyed

by airline jets the day before. I mean, how ridiculous does that sound?

We didn’t believe her, despite her serious attempts otherwise, until we

stopped at the Sinclair in Jenson for shakes and saw the TV sets replaying

the disaster again and again. I figured that at about the time it happened,

we were busy digging up tamarisk on a sandy, shady beach without a care

in the world. A very strange thought, that. We emerged from that bliss

of ignorance to a whole different animal. And I’d have to say that not

seeing another person outside our group for 4 days was the best part of

the whole experience. Even great places lose their charm when you’ve got

to share them with other bipeds. Anyway, that’s how the trip ended, the

trip of a lifetime, really. It was a fantastic ending to my summer at Dinosaur.

I packed up and left for home one week later and I’ve been dreaming of

going back ever since.