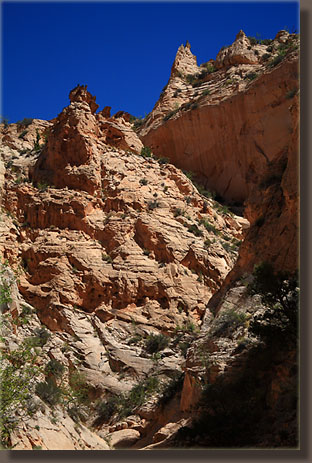

| Upper Cottonwood Canyon,

Utah

Location: Grand Staircase-Escalante

National Monument, southern Utah; near Page, Arizona

April 29 2009 Early morning, and I am attempting

to get a permit for the right to go see The Wave, a geologic formation

that probably everybody in the free world has seen in pictures, even if

they didnít know the name. Itís located on the nebulous, confounded borderland

between Utah and Arizona, west of Page. I fill out my official entry form,

wait around for 30 minutes in the air-conditioned lobby of the BLM Pariah

Ranger Station and chat with a German tourist about her travels in Americaís

canyon country. Germans love canyon country. Every canyon you come to in

April you can find at least one German hiker there, and lay good money

on finding more. Why Japanese, French or Italian tourists stay away from

these areas I canít say, but the Germans are silly for them. Google any

popular canyon in the western US, and you are likely to see a German discussion

forum in the top 10 results. Pick up any coffee table picture book on the

westís canyon country, and Iíll lay 2 to 1 odds it was produced by a German

photographer. Browse the Panoramio entries in canyon country on Google

Earth, and a third of them have German titles. Half the links to my canyon

hike webpages are from German newsgroups, most of them I canít even read.

Perhaps, given all that, itís my Grandmotherís German blood that drives

me, too, into the desert inferno, to seek out the hidden sandstone pleasures.

In the waiting room, the young female German tourist I am talking with

estimates that a quarter of the 66 people in the room are German.

I watch all the people in the room with renewed interest, studying their body language, but other than the loud German gentlemen on the other side of the room who reveals his nationality with his boisterous accent, I canít pick them out, but it passes the time. I consider that I wouldnít be at all confident trying to pick Americans out of waiting room in a foreign country, but then Iíve never taken that chance. Given the number of entries in the drawing, and an assumed average group size of 2, I estimate the odds of me getting a permit are about 1 in 13, or about 8%. Not so good. The BLM staffer announces this is the highest number of applicants this year. Lucky me to arrive on just this day and be part of the glut. The drawing comes, passes, and I donít get a permit. I briefly consider going anyway, I mean, do they have cops out there arresting people for not having a permit? The permit costs some money, I canít recall how much, so maybe if one gets a ticket you just consider the fine the price of a premium pass to the Wave. Anyway, one could find it pretty easy to hide from the MAN if you saw him coming. Out there in the pink sandstone jumble of fins and canyons, it would seem pretty easy to elude any terrestrial pursuer. Might even lend some adventure to the story. Too bad Iím no lawbreaker, and I drop the whole idea. In lieu of that, I ask the friendly woman who spun the lottery ball roller about good, close hikes. I want close because the brilliant sunshine across yonder plateau has been burning for over 3 hours now, and Iím itchy to get out into it. She suggests Cottonwood Canyon, and produces a hand-drawn map to show me how to get there. I am not prepared with the right maps for this area, as I had foolishly trusted to Karma to get me a permit to see the Wave, so I use this one. I drive east on Hwy 89, following

along on the crude, hand-drawn map, and take Cottonwood Canyon Rd north

towards the Paria River. Misreading the map, or rather simply making an

error in judgment from a terribly-whacked sense of scale in the map, I

take a wrong turn just a mile up the road, and drive many miles in the

wrong direction over dusty washboard before deciding to turn back and try

a different route. The map was hand drawn, and not even close to scale,

nor did it include any side-roads that might lead the unwary driver astray.

I find the road that runs along the Paria River, a rough route that Iím

glad is dry because it looks like only recently it was a mucky, impassable

mess. I drive north and soon I see Cockscomb Ridge, an alien-looking fin

of jagged white and red banded rock that stretches for miles. I finally

reach a labeled trailhead just off the road, and park the car.

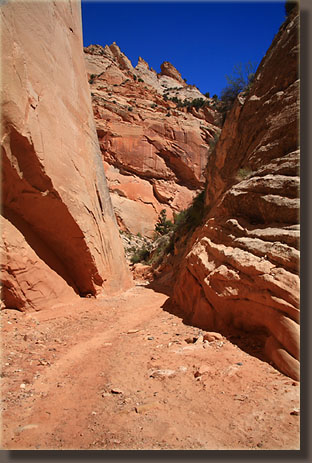

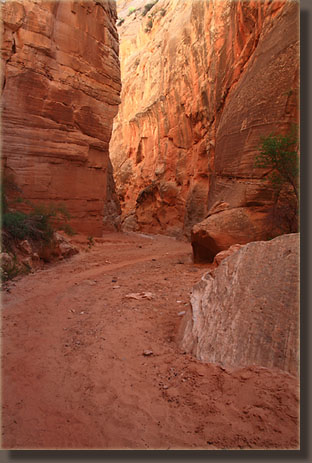

The canyon floor beyond is wide and composed of loose, course sand, which drags at my heels and slows me down. It is painfully dry in the canyon, and without the rustle of water or the lilting call of water-loving canyon wrens, it is eerily quiet. There is some vegetation in the canyon, deep-rooted stalwarts that have roots thirty feet deep into the moist soil, but no trees or riparian plants, mostly just rabbitbrush, some dry grasses and cactus. The dominant feature, common to Utah, is rock. The walls of the canyon are about 30 feet apart, and maybe a hundred feet tall. Pretty impressive. The canyon takes a sharp right bend and heads north between two high walls of jagged rock. It is very easy going. I take a side trip to the west up a canyon that looks interesting, but it curls around to the south and ends in a box in no time. Still, one has to check these things. Back in the main stem, I continue north, savoring the shady, narrow spots, and hauling fast through the wide, less-than-thrilling sections. I stop often to take nice, long exposures of the canyon, sitting down and bracing my elbows on my knees to keep the camera steady in lieu of the tripod that I left in the car to save weight since my foot is hurting. In the shady places, I fail utterly to keep the camera still enough, and I regret not bringing along my tripod. About an hour up the canyon I come

to a dryfall choked with a big log. After pondering for a moment where

such a large log could have come from in this dry, desert scrubland, I

first try to bypass on the right via a narrow ledge, but as it rises up

and becomes narrower, the height gets to me, so I back off and inspect

the logjam at the dry fall itself. I am able to shimmy up through a crack

between the log and the rock, and then scramble along the log to the canyon

beyond. No problem, aside from a fleeting sense of claustrophobia whilst

squeezing through the crack. Another thirty minutes of hiking, however,

convince me that the dryfall was probably the wise choice for turning around,

since the canyon is shallow and uninteresting beyond that point. I stop

in the shade and snack, chugging water to catch up for all the water I

should have been drinking all along but was too busy to do. I remove my

shoes and socks, and let the warm desert air and unimpeded sunlight dry

my damp socks. In the shade of an overhang, examining the sandy wash

devoid of footprints up ahead, I savor that wonderful feeling of complete

solitude for 10 minutes, 20 minutes, somewhere I lose track of time. I

try to absorb everything I can about this place, the smell, the feel of

the dry air in my nostrils, the cool of the sandstone on my back, the loneliness

of the place and the multitude of cracks and potholes just over the rim

that have probably never been trodden on by human feet. There are so many

canyons in Utah alone that I wonít live long enough to see them all. I

canít even begin to comprehend all the spots in the country, the world,

(the universe?) that I should see but never will; a thought that

is at once saddening and exhilarating. No matter how many days you spend

here, thereís never an end. Itís an endless world to see, and, aside from

a superficial similarity, no two spots are quite the same. As always, that

last thought provides motivation to move on, to keep it rolling, to see

more. Iím 31 years old now and timeís ticking away, now as always, in a

disarmingly serene parade of faces, places and events. I put my socks and

shoes on and lurch upright, then turn back and hike out the way I came

in, seeing nobody at all along the way, and arriving back at my broiling

car around 2:00, eager for another canyon to explore. Always another canyon

to explore.

|

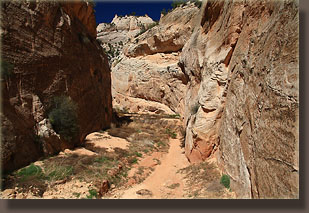

Near the beginning of the hike

|