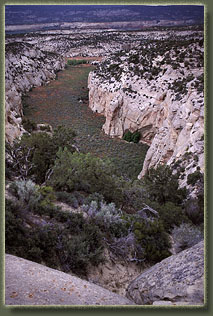

Bull Canyon,

Colorado

September 20, 2003 Late summer on the Colorado Plateau has a sweetness all its own. The air is even drier than usual, with a crisp blue sky portending fall. The mornings are cool, the afternoons hot. The sun rises only ¾ of the way overhead, even at noon, casting a glazed orange sunshine across the dry sandstone. The spring flies are gone, the springs are drying up and the mosquitoes have taken a hike for the hills. Even the swarming gnats are nowhere to be found. The air seems quieter and still, with only the call of the unseen canyon wren to break the silence that is often so complete you can hear your own heartbeat after scrambling up a steep incline of rock, perhaps pulling yourself up the last bit with the help of a twisted sagebrush trunk, 30 years old and barely 3 inches across. On just such a fantastic morning, Griff and I got an early start from the Plug Hat picnic area off the Harpers Corner Rd south of Dinosaur National Monument, the greatest monument that nobody knows about in the country. Getting into Bull Canyon is no simple task, as the drop from the canyon rim to the bottom is a 600’ drop in just 1500’ horizontal spread, a slope of 38%. In addition, much of the navigable terrain is covered with thick juniper that has lower branches that bend about as readily as steel gates. The going is not easy. Griff and I dropped off the road at a likely spot, and headed down swiftly, picking our way through the jungle of juniper, trying to avoid the cactus. We reached the rocky canyon bottom in the hanging canyon portion, that slick-rock segment in the upper reaches that ends in a sheer drop of about 60 feet. We explored both up and downstream, enjoying the downstream section of narrows to the hilt. What a great spot, especially sweet since we had no idea going in that such a drop existed. I edged up on my butt to the dropoff, and looked down through fluted, carved sandstone to the cottonwoods growing in the wider canyon below. Backtracking, we reached a point where we could walk down into the lower canyon, and once in the canyon proper, travel was much simpler. The channel was wide and sandy in most places, but occasionally rocky, with minor dropoffs. We explored every side canyon that looked interesting, most of them boxing up almost immediately, but some, especially those on the south, looking to taper upwards and provide easy exits. One box canyon in particular formed a round alcove with an overhanging ledge, and sheltered a single large box elder tree, gleaming green against the light yellow rock, seemingly a perfect place to sit and enjoy the silence in the shade. Box elder may be a weedy tree in the suburbs, but its shade is a welcome presence in the canyons of the Colorado Plateau. On a hot summer day in the desert, I can think of few better places to pass the noon hours than in a shady alcove filled with the happy green leaves of box elders. The bottom of the canyon was wet, and in the wider stretches, filled with bullrush, cottonwood and willow. Wearing sneakers, we sloshed through the thin depths of clear water. I enjoyed the juxtaposition of the hot sun on my shoulders with the cold water on my legs. Clouds rolled in, and rain looked very likely. The gorge widened, sagebrush began to dominate the high riparian benches, and the map divulged that were reaching the end of the canyon. We looked south up a long side canyon with steep walls, trying to predict if it offered an exit, or a box. We decided to take a chance, and headed south. The wide, flat corridor was littered with cattle dung and criss-crossed by stock trails. Under an alcove, we came upon a pile of cow shit so massive it had to have been 3 decades in the making. I like cows, and I don’t begrudge grazing cattle in reasonable numbers, but I have to wonder how compatible large ungulates are in a desert ecosystem that never evolved with large ungulates, a wilderness study area at that. Other areas I’ve visited have been impacted by overgrazing in the following ways: channel erosion, channel incisement, lowered water table, lost water holding capacity, increases in upland shrubs and grasses, losses in native plant and animal diversity. It appears by all indications the very same things are happening in Bull Canyon. A very delicate ecosystem such as a desert riparian area simply cannot absorb the massive disturbance a herd of thousand-pound hoofed animals brings with it. How did the canyon look before cattle? Wouldn’t it be nice to know? I suspect the canyon was much more lush and green than it is now, with a higher water table due to a robust riparian community that held water in the system much longer than it can now. The canyon would have supported many more birds, frogs, fish and snakes than it does now, and even some deer and large raptors. Cottonwoods and willows would grow in greater abundance, providing more shade and more evaporative cooling. The destructive influence of cattle is everywhere in evidence in the areas in and around Dinosaur National Monument, though the ranchers will argue differently. I don’t begrudge the cows, they are just doing what cows do, but I do begrudge the ranchers and managers who allow public lands to be denuded of diversity for the sake of skinny profits and politics. Griff and I reached the south end of the side canyon, and then climbed steeply upward through stunted pinions and junipers, often using the tree branches as ladder rungs to climb higher up the steep rock. If not for the trees, I wouldn’t have attempted to climb so steep an incline of rock. Near the top it looked for a few minutes as if we would get boxed out afterall, but after contouring around to the right, we found a passable route up. At the top, we stopped and rested, having completed the first uphill walking of the day. The clouds were thick, but it was still warm. We took a walk back along the east rim of the side canyon to examine the route we had come up. Turns out we probably made the best of the thing, and heading in any other direction on our way up would have left us high and dry. The walk back to the truck

was a bit of a cluster. With only a compass, we navigated our way back

to the road, but not without straying off-course numerous times. In all,

I think we took about an hour longer heading back than it should have taken,

but that’s OK, we had nothing to do but find a campsite before dark. We

reached the truck around 5:00, completing the day hike in about 10 hours.

Mileage-wise this hike shouldn’t take that long at all, but all those side-canyons

and quiet alcoves suck up a lot of time, and you hate to pass any one of

them up, wondering what hidden splendors they shelter. It would be folly

to rush through Bull Canyon too quickly.

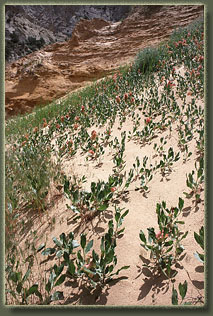

Prairie Dock in middle Bull Canyon

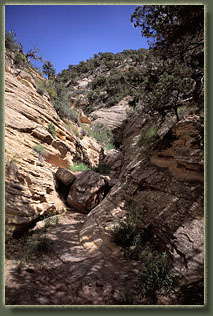

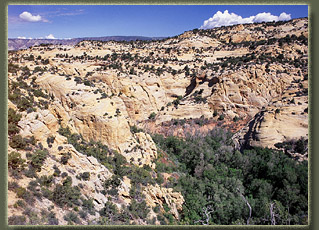

Dry sections of the lower canyon

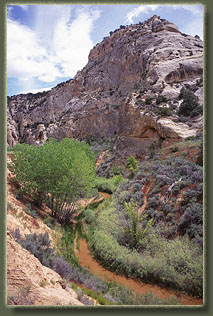

Cottonwoods in Bull Canyon

Last Canyon, the exit we took to get out of Bull Canyon to the south

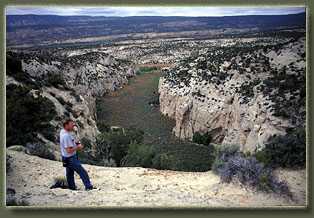

Griff relaxes at the top of the exit canyon

Checking out the exit route

The exit route

Back at the canyon head, late afternoon

Bull Canyon Rim, late afternoon the clouds break a bit

Evening light on Bull Canyon rim |

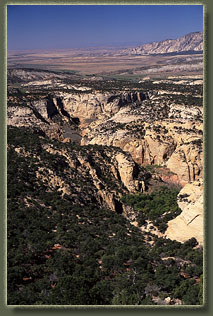

Bull Canyon Rim

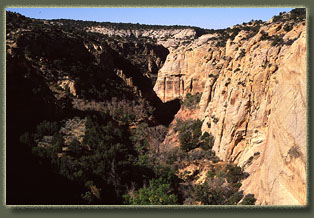

Bull Canyon, as seen from the head of the canyon

Upper Bull Canyon

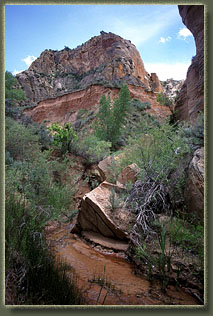

Descending into Bull Canyon

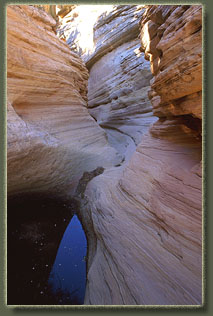

Dropoff in Upper Bull Canyon

Droppoff in Upper Bull Canyon

Looking down on cottonwoods below the dropoff

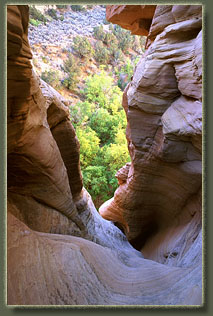

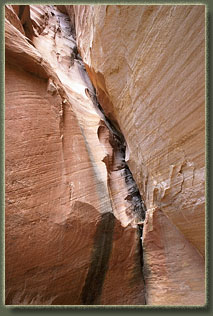

Narrows in Upper Bull Canyon

Bull Canyon, looking upcanyon

Middle Bull Canyon

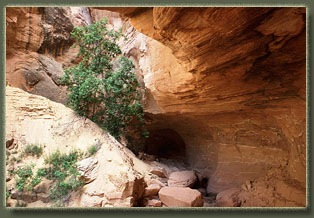

Shaded alcove side canyon

Shady alcove

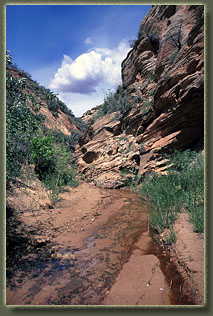

Middle Bull Canyon, the wet part

Open, shallow section of the canyon  |