-

-

BLUE LAKE

-

-

Location: Rawah Wilderness, northern Colorado

-

Maps: USGS Quad 1:24K Clark

Peak :, Trails Illustrated 1:40K

Cameron Pass #112

-

Access: Hwy 14 west 53 miles from Ted's Place to the Blue Lake trailhead

on the north side of the road.

-

Trailhead: NAD83 zone 13 427584e 4492445n Elev: 9450'

-

Trail: 7 miles one way. 1300 ft elevation gain. Begins in forest,

several bridged stream crossings, ends in alpine tundra.

-

Fees: None

-

Dog Regulations: Voice control in National Forest (1st 1.5 miles),

leash control in wilderness.

-

Weather: Current

and recent conditions Local

Forecast

-

-

November 12, 1999

-

Despite

failing to actually reach the destination on two previous attempts, once

due to bad weather and another due to a 3:00 ecology class that cut the

trip short, I was trying once again to grunt my way up to Blue Lake on

the west side of Cameron Peak, the namesake of the popular highway pass

in northern Colorado. The route drawn out on my USGS map looked like 5

miles, the Colorado Ski Patrol map estimates 7. Either way, the trail is

not terribly long, but the terrain is not flat. The countless rolls and

slants that the trail winds over make it much more difficult than one thinks

when looking at the map. The hills strain the legs, and the ever-present

snow dulls one's step. Even so, I determined to make Blue Lake regardless

of obstacles or weather, and I planned the day accordingly.

-

-

I was up at 6, just before a beautiful November dawn. I sat

behind the steering wheel of my girlfriend's Toyota Corolla (borrowed for

this occasion) and was on the road out of town, into reality, by 7 AM.

The front seat was loaded with a bag full of food, water, warm clothes

and my camera, while the back seat was loaded with my faithful canine adventure

companion, Frankie, ever eager to wander on pointless discourses over hostile

terrain with me. Without traffic on Highway 14 up along the Poudre River,

I made it to the trailhead in 1.5 hours. There are few things more frustrating

than planning an outdoor excursion, getting up early and driving away from

the smog of the city only to be held captive in your car by inclement weather.

It has happened to me on occasion, but fortune smiled on me as I stepped

out of the car into a dreamlike day. The sun was low on the horizon, casting

a friendly warm glow in the morning mist of the pine forest which surrounded

me. The sky was without clouds, and though cheery clouds on occasion will

add to the enjoyment of a day's hike, in the mountains it is usually more

comforting for clouds to be absent, for if they be friendly one hour, they

will be angry the next. It was unusually warm for November in Colorado

at 10,000 ft, and the snow was conspicuously absent. A bit of a breeze

moaned through the pines, but it was mild. The lot was empty as I shouldered

my pack, and I looked forward to a solitary trail.

-

-

-

The first bit of trail led through a very deep growth of

lodgepole pine and subalpine fir, casting a cool darkness that belied the

brilliant sunshine outside the dense evergreen canopy. The ground was carpeted

with bryophytes, resembling, at a perfunctory glance, well-groomed turf.

Before I had gone 200 yards, I had to stop to pull off my down vest, gloves

and cotton flannel. It is always difficult for me to correctly guess a

comfortable layering of clothing while hiking. The body heats up rapidly

while strutting over rough terrain, such that one is often comfortable

in a t-shirt at 40F, as long as movement is sustained. Cessation

of movement invariably invokes an instant chill. The sunlight and

wind both wreak havoc on comfort-levels, having opposite effects but both

appearing and disappearing as one enters valleys, rounds corners or encounters

dense forest. Thus, maintaining comfortable body temperature is a

challenge in itself.

-

-

A bridge crosses Sawmill Creek, a stretch of water that flows

rapid in the confines of a small groove sliced out of the forest soil.

It is nice, fresh and vibrant. If I wasn't so terrified of Giardia,

I might give in and venture a drink straight from it. Beyond the bridge

the trail widens and appears to be well maintained, that is, free of ruts,

trees, rocks, etc. Frank enjoyed himself immensely from what I could

observe; constantly hunting the unseen chirps and chatters in the underbrush

beyond. At about 1.5 miles, we reached a sharp bend in the trail

that overlooked Chambers Lake, a deep blue bowl larger than just about

every lake in the region. We stopped only for a moment, for I had

gazed at this sight before. I was after the next thrill.

-

-

I hiked at a fast pace, about 3 mph I figure, and felt great.

Distant rumblings in my belly warned of the need for an early lunch.

Nothing makes me hungrier than hiking. I ignored it. Mind over matter,

and belly. Lunch should come at the halfway mark of the trip and

not before. Soon we came to another bridge, not nearly as well-kept

but quite functional. The stream it spanned, Fall Creek, was much

smaller than the first, yet not less inviting. Immediately on the

other side of this stream lay the imaginary demarcation delineating "normal"

forest from "wilderness" forest, a distinction whose only implication is

that you can no longer build a gas station or ride motorbikes along the

trails. To George Bush, there apparantly is NO distinction at all.

The trail likewise becomes narrow and less "groomed"; consequently my approval

increased.

-

-

It is through this section of the trail that I got tired.

The path led up steep, long slopes that made my calves burn and ache, then

led down steep, long slopes that fatigued my quads and jammed my toes.

At 9:30 we made our first stop of the trip on an upward slope in the shade.

I sat on a conveniently located log and ate some peanuts, throwing Frank

a nut or two to keep him happy. Amazingly, he always enjoys whatever I'm

eating. Ten minutes later we were off again, up and down on the trail.

-

-

The sun rose higher in the sky so that it consistently lit

the path before me in flecks and streaks of brilliant white. The sun felt

good, and warmed me in the chilly breeze. I knew by then that the wind

I was feeling gently flitting by would be a gale on the open alpine shores

ahead. I could hear distant whistles of gusts through the tree tops.

-

-

A third bridge came up on the trail, this one spanning an

even smaller and shallower trickle than before. This too was Fall Creek,

but in its infant form. In fact, the bridge is quite superfluous, as any

reasonably fit person could manage to leap over it. While I utilized

the luxury of the bridge, Frank rebuked, and splashed noisily through the

icy water. (Although he took the bridge on the way back) I halted

briefly among the moss-shrouded firs to consult my map. I had reached the

point of my turn-back the year before, where I had met two men who told

me (and lied) that the lake was still 4 or 5 miles away. I had since

doubted that assertion, and the map told no lies. I was close, and getting

anxious. By now my hunger had waxed voracious, and I was eager to devour

my lunch on the shore of the advertised attraction. Confident that my destination

was imminent, I continued on.

-

-

Here and there Frank would halt abruptly, dashingly handsome

in his rigid regal point to the quarry. A positive word from me and he

would tear off like a greyhound, only to have his would-be lunch scurry

up the tree and chatter angrily at him from it safe perch high above. On

rare occasions I've watched Frank, in a fit of blood lust, scale the trunk

of a tree 10 ft or more before his momentum gave out and his claws slipped.

To date, he has recorded 0 kills.

-

-

The landscape changed rapidly as I plodded quietly along.

Dense lush forest gave way to open brown tundra. A small wooden sign forbade

camping within 1/4 mile of the lake. I walked 300 yards further and there,

to my right, was a giant glacier-carved bowl filled with water. The time

was 10:35. It was indeed Blue, but only on the edges that yet were free

from the smooth expanse of silver ice that lay on the surface, crisscrossed

with white cracks resembling a spider's web. The shoreline was rocky, and

the trees were few (being alpine tundra). The predominant feature of the

area was scrubby brown grass, and the wind howled under the white sun.

-

-

The trail didn't seem to go down to the lake shore, which

was several hundred feet down a loose slope, but instead threaded around

and over a distant ridge, onward to Tunnel Creek Campground 6 miles away.

Given the bleakness of the surrounding terrain, I decided to venture a

climb up the imposing slope on the west, 320 feet, to Hang Lake, Blue Lake's

little brother. Hang Lake is not visible from the trail, and no trail at

all was apparent to this destination. The only indications I had of the

presence of any body of water was the map, and two ravines filled with

ice cutting the slope toward me. One, or both, lead to the lake. I wasn't

sure which ravine to take, so I guessed and took the wrong one.

-

-

The going was hard to begin with. I was over 11,000 ft by

then, and my leg muscles were tight from the fast-paced 6 miles they'd

just reeled off. In addition, the slope kept getting steeper and steeper,

and while Frank the Wonder Dog trotted up with typical dog ease, I found

myself stopping every 10 steps to sit down and pant. I planned my ascent

to the obvious ridge up above in 8 thirty-foot intervals. Each time I achieved

a landmark, I rested. I realized too late how poorly my route choice had

been. The slope I was on became absurdly steep, and wholly consistent of

loose rocks and gravel. Every step I took caused me to slide back one,

yet I couldn't bear the thought of turning around at that point. Great

maneuvering was required to edge myself to the left, on all fours but almost

erect, to a stretch of solid earth anchored by dwarfed timberline firs.

It was on my way over that I lost my lens cap. It tapped a rock and bounced

free. I watched unsympathetically as it bounced and slid 50 or 60 feet

down. It finally disappeared under the loose rocks, destined to be buried

for the next 12 millennia. Civilized ants will one day ponder the meaning

of NIKON.

-

-

By the time I reached solid footing, all strength had deserted

me, apparently going directly to Frank, and my muscles quivered with fatigue.

Ruefully, I looked to the south and saw Hang Lake shimmering some 50 feet

lower and 300 feet to the south of my current precarious perch. Dangit.

Couldn't be helped. I had targeted the ridge above me, and I was going

there, by gosh. I pressed on 10 steps, rest, 20 steps, rest, 30 steps,

big rest, 40 steps, and I was there. I reached a small area of flat ground

on the edge of a giant boulder field that sloped gently up towards a spire

that stabbed another hundred feet towards the sky. This was Clark's Peak.

-

-

I immediatly broke out my lunch and ate. In matters of etiquette

I am reasonably refined, but something animalistic came over me on top

of that ridge. I tore into my food without thought for taste or even

chewing. The cold, the wind, the long hike, the aching muscles; all contributed

to an eating style wholly unacceptable within city limits. I ate voraciously.

My hands were heavy and unresponsive from the cold and rough treatment

up the loose rocky slope, but they managed to shovel in food all the same.

I began to enjoy the mistake I had made as I commanded a magnificent view

of both lakes below me. Cameron Peak, opposite Blue Lake, rose up even

higher, a slumbering hulk of raw rock with, oddly enough, absolutely no

snow to grace its cap in November.

-

-

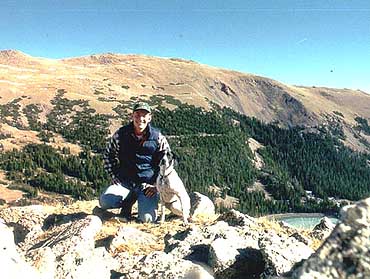

After eating all available food and throwing Frank some peanut

shells to abate his begging, I pulled out the camera and loaded new film.

I also donned my previously-shed warm clothes to combat the wind. I took

a few photos of Frank and I and the surrounding area before finding a reasonably

sheltered crook in the rocks to relax. Turned out to be only partially

shielded, for I soon took note that the wind blew alternately from two

opposite directions. Periods of calm interluded the raging wind, and in

those times I could've napped for hours. I tried, but the bite of the wind

prompted me to keep moving.

-

-

The clouds began to move across the sky in ever-increasing

numbers. They sailed along with the same apparent speed and mechanical

precision of a locomotive. It always amazes me how fast clouds move to

the terrestrial observer at 12,000 ft. At that elevation, the clouds often

pass by below you. When they blocked out the sun it became cold, instantly,

but rarely did this last for more than 10 seconds before they were out

of the way. Although the clouds were puffy and white, I was wary of what

lay behind the wall of rock to the west.

-

-

I made my way toward Hang Lake by scrambling over sideways

and crossing the aforementioned ravine. I encountered thick, knotted growth

of elevation-stunted fir. This peculiar growth pattern results from the

fact that the ground freezes solid in the winter and the plants have no

access to water. For the most part they are buried beneath snow which

blocks out light, inhibiting photosynthesis, thus inhibiting respiration

and subsequent water loss to evapotranspiration. However, if any part of

the plant protrudes above snow line, it will photosynthesize, respire,

and lose water which it cannot replace, whereupon it will dessicate, and

die. This growth pattern results in a plant architecture known as Krumholtz,

after the botanist who first described it. Thus is the stunted growth maintained,

and a century-old tree may be but 5 feet tall. Absolutely impenetrable

when taller than 4 feet, Frank and I picked our way through the maze of

Krumholtz, drawing closer to the lake most of the time. As we neared the

shore, an especially sharp wind howl prompted me, reflexively, to look

up out onto the lake whereupon I saw something I'd never seen before. A

tight whirlwind had sucked water up in a vortex 70 ft high to create a

fleeting tube of white mist. I pulled up my camera to capture the mountain

waterspout, but by the time I had the shutter speed set, the show was over.

I waited around for the encore performance, but it did not air.

-

-

The water in the lake was crystal clear, true to mountain

lake form, and we strolled along the shore towards the outlet, and the

formerly passed over ravine down to Blue Lake. I snapped a few photos

and plunged through the Krumholtz to the ravine, my easy ticket back down.

For all the work invested getting up, I made it down in less than 15 minutes.

-

-

As I began backtracking into the sheltered forest, I removed

clothing as the wind was diminished.

-

The way back was more downhill, but because of my tired legs

and a raging headache, took me 45 minutes longer to complete. I stopped

a few times, at one point endeavoring a nap to rid myself of the throbbing

headache, but the sunlight waned and it grew cold enough to induce continued

movement. We got back to the car, and completed the hike, at 2:45.

Thus was the destination of Blue Lake checked off my list.

-

-

-

-

-

-

HOME

Back To Camping

NEXT

-

-

Page Created December 16,

1999

-

Updated January 3, 2003