Sunday, October

12

After

two days of driving around Charlottesville, Virginia, in between a rehearsal

dinner on Friday night and an evening outdoor wedding at a pastoral vineyard

near Earlysville on Saturday, we steered the rented Saturn L200 into the

South entrance of Shenandoah National Park at Waynesboro. I was beginning

to become dangerously fond of the L200, as it completely out-classed my

Saturn SL2 at home. It was 10:00 Sunday morning. Intentionally, we had

purchased a James Taylor CD for the purpose of imprinting our experience

on the music. I find the best way to remember anything is to hear the music

associated with it. For example, Def Leopard tunes make me recall those

awkward days of the 6th grade. To this day, I hate Def Leopard. Thus, the

formerly unheard James Taylor became the official balladeer of this trip.

“In my mind I’m going to Carolina.” To a western boy like me, Virginia’s

about the same thing. After

two days of driving around Charlottesville, Virginia, in between a rehearsal

dinner on Friday night and an evening outdoor wedding at a pastoral vineyard

near Earlysville on Saturday, we steered the rented Saturn L200 into the

South entrance of Shenandoah National Park at Waynesboro. I was beginning

to become dangerously fond of the L200, as it completely out-classed my

Saturn SL2 at home. It was 10:00 Sunday morning. Intentionally, we had

purchased a James Taylor CD for the purpose of imprinting our experience

on the music. I find the best way to remember anything is to hear the music

associated with it. For example, Def Leopard tunes make me recall those

awkward days of the 6th grade. To this day, I hate Def Leopard. Thus, the

formerly unheard James Taylor became the official balladeer of this trip.

“In my mind I’m going to Carolina.” To a western boy like me, Virginia’s

about the same thing.

It’s

always hard to match those first few minutes cruising down a sun-dappled

National Park road after exiting the super-beltway, on which your car is

herded along by the sheer momentum of a thousand others at 80 mph. Sunshine

streamed through the myriad colors of hardwood leaves in the crisp, October

morning air. Red and orange oaks, blazing yellow hickory and tenaciously

green tulip trees, barely frosted with yellow, lined Skyline Drive, casually

leading us north along the crest of the storied Blue Ridge Mountain. The

thin river of dark pavement curved and streamed around rock walls and through

a forest so dense at times I could see no more than 10 feet into its depths

before my vision grew confused at the jumble of shapes, colors and textures.

For the automotive-tourist, Skyline Drive is perfect. Dozens of vehicle

pullouts line the main road on both sides, affording red-blooded Americans

the satisfying option of “seeing” the park without ever getting out of

the car. Hell, we observed some folks who wouldn’t even put their car in

park before cruising on down the road. Now THAT’S entertainment! We enjoyed

the views from several pullouts along the way. Each one, and a significant

portion of the road through the park, was contained by a rock retainer

wall built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. Being so close

to Washington DC, Shenandoah was naturally a great spot for FDR to demonstrate

the utility of the CCC. It’s

always hard to match those first few minutes cruising down a sun-dappled

National Park road after exiting the super-beltway, on which your car is

herded along by the sheer momentum of a thousand others at 80 mph. Sunshine

streamed through the myriad colors of hardwood leaves in the crisp, October

morning air. Red and orange oaks, blazing yellow hickory and tenaciously

green tulip trees, barely frosted with yellow, lined Skyline Drive, casually

leading us north along the crest of the storied Blue Ridge Mountain. The

thin river of dark pavement curved and streamed around rock walls and through

a forest so dense at times I could see no more than 10 feet into its depths

before my vision grew confused at the jumble of shapes, colors and textures.

For the automotive-tourist, Skyline Drive is perfect. Dozens of vehicle

pullouts line the main road on both sides, affording red-blooded Americans

the satisfying option of “seeing” the park without ever getting out of

the car. Hell, we observed some folks who wouldn’t even put their car in

park before cruising on down the road. Now THAT’S entertainment! We enjoyed

the views from several pullouts along the way. Each one, and a significant

portion of the road through the park, was contained by a rock retainer

wall built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. Being so close

to Washington DC, Shenandoah was naturally a great spot for FDR to demonstrate

the utility of the CCC.

Like a kid in a candy

store, I was chomping at the bit to get out of the dang car and start slapping

my boot soles on the packed clay. We parked the car at Turk Gap, where

I endeavored to strike quickly up Turk Mt and return to the car within

an hour. Andra felt she would rather sit in the quiet woods and read while

I sweated my way up the mountain, so she did her thing and I did mine.

Even more exhilarating than the first few miles of road inside a national

park, the first few thousand yards of trail are usually the most easily-recalled

segment of a trip. The woods were cool and heavily shaded on the trail

to Turk Mt, with a thick, moist air that one could almost chew on after

spending so long in Colorado’s dry winds. Something like 20% of the leaves

had fallen from the trees already, with most still hanging tenuously, waiting

for that first full blast of winter air to knock them down. The yellow

hickory leaves seemed to make the sky glow an even more luminous shade

of blue, and my neck grew tired constantly shifting from looking up at

the spectacle of the leaves against the sky and looking down to steer clear

of roots and rocks across the trail. I followed the Appalachian Trail (AT)

south for a short distance before turning off west to Turk Mt. Along this

trail I came across an American Chestnut and thrilled at seeing something

in living color that I had read so much about. It was small, and

dead at the top, as most are apt to be these days. Fungal fruiting bodies

covered the cracked twigs near the top. I would see many more chestnut

sprouts later on. The trail led downhill from the AT to a saddle

between the main ridge and the mountain, then rose steeply up its eastern

side, 500’ to the summit. I walked quickly with the bright sun on my left

shoulder, stepping lightly over rocks and crunching leaves underfoot. I

had purchased a brand new pair of Asolo hiking boots just a week earlier,

pressed into it by the rip that developed in the sole of my old pair of

Vasques only two weeks before. I passed only one group, a family of four

with small kids enthusiastically running ahead of each other on the trail,

and off. Nice to see some families still get out to walk on the trails.

The top of Turk Mt was heavily wooded except for the slope to the west,

which was occupied by a young couple trying to figure out their digital

camera. Digital cameras, like personal computers and automatic coffee-makers,

tend to be less of a convenience than anyone who doesn’t already have one

could possibly imagine. In all directions, rolling mountains melted together

into the horizon. Shades of red, orange, yellow and green were melded together

in a festival of fall color. I tarried but a moment up top, then strode

quickly back down. On my way down, I could imagine Confederate soldiers,

younger than myself, tromping through the leaves with their rifled muskets

lazily shouldered over rag-tag uniforms (multi-forms?). I could imagine

natives  quietly

stalking deer in the dense underbrush. A vision of an early pioneer hunting

rabbits popped into my head. The history of the place was palpable. Ditto

for the moisture. The humid air allowed no sweat to dry, and I constantly

wiped my brow as I walked downhill. I tried to imagine what kind of sticky

mugginess enveloped this place in August, and failed. As I neared the spot

where I left Andra, I turned off the trail and heard her whistle from 20

yards away. The woods were so thick, I couldn’t see her, but followed the

sound right to her. We sat in the leaves and I told her about the grand

sight she missed, and the chestnut tree. We listened to folks hike through

the leaves on the nearby trail. quietly

stalking deer in the dense underbrush. A vision of an early pioneer hunting

rabbits popped into my head. The history of the place was palpable. Ditto

for the moisture. The humid air allowed no sweat to dry, and I constantly

wiped my brow as I walked downhill. I tried to imagine what kind of sticky

mugginess enveloped this place in August, and failed. As I neared the spot

where I left Andra, I turned off the trail and heard her whistle from 20

yards away. The woods were so thick, I couldn’t see her, but followed the

sound right to her. We sat in the leaves and I told her about the grand

sight she missed, and the chestnut tree. We listened to folks hike through

the leaves on the nearby trail.

Up the road we went

in the car, stopping at some of the pullouts to study the curves of the

valleys below, passing by others. Somewhere, shortly off to the west, lay

the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. “Oh, Shenandoah, I long to hear

you; Look away, you rollin' river; Oh, Shenandoah, I long to hear you;

Look away, we're bound away; Across the wide Missouri.” I don’t think that

song has anything to do with the Shenandoah River but it’s a fine tune.

The words Shenandoah Valley conjure up images of Stonewall Jackson’s brigade

deftly outflanking Union armies twice its’ size, holding the Union out

of central Virginia for over 2 years. I also picture Phil Sheridan’s cavalry

burning farm houses and slaughtering everything with four legs in an attempt

to cripple the Confederacy. Seemed to work, I guess. The United States

has always excelled at total war. The entire trip into Virginia was made

with constant thoughts of the history that lay steeped in the land.

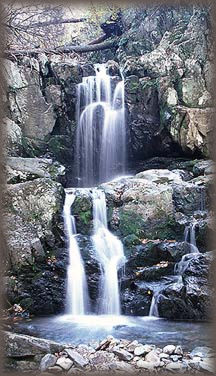

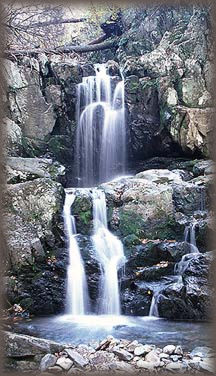

At Jones Run, we shouldered

our packs in the afternoon sun, and set off down the trail towards one

of the more popular destinations in the park, Jones Run Falls. The sky

quickly grew overcast. The trail led downhill steeply, east of Skyline

Drive, with few switchbacks. A straight-and-to-the-point kind of trail.

I liked it immediately. Andra and I played “What tree is that?” for a long

portion of the trail. Coming from the west where giving the answere of

“spruce” is a 50/50 chance at any location, the game held particular challenge

here. The game’s added challenge was contained in the fact that most trees

had branches no lower than 50 feet, so a keen eye was also required. It

seems odd, this fascination we humans have for naming things. What difference

does it make if something has a name? It is still the same thing whether

I call it a hickory or a zampunbossel. Think on that one. I am not the

first to question this human tendency, but the subject bears rehashing

now and again. We reached the falls ahead of the pack, and I quickly set

up my tripod to snap a few shots prior to the crowd’s arrival. I succeeded.

Jones Run Falls is a beautiful, 80-foot waterfall with multiple falls beyond

of significant height. Up to this trip, I could count the number of falls

I had hiked to on one hand. Now I need several hands to do so (and they’d

come in handy for dishwashing too).

Andra

and I made our way downstream as others filed into the rock flat below

the falls. Leaf-covered rocks lined the creek, creating a delicious dichotomy

of yellow and red speckles on black rock. The trail continued downhill

through a deep canyon, with walls much to steep to camp on or climb up.

Nothing to do but walk on. At the confluence of the Jones Run and Doyles

River, we fanned out to find a flat spot of ground to sleep on, but found

nothing except bramble-covered slopes under imposing oak trees. In retrospect,

it wasn’t too bad, but at the time we felt we could do better. Maybe it

was just that I wasn’t quite ready to stop the sightseeing for the evening

yet. We started up the Doyles River Trail, a steep and rocky path leading

uphill along the south side of Doyles River. Two magnificent falls stretch

out over a section of the stream, and I regret we had so little time to

dally at them, but darkness was approaching fast. Just uphill of the upper

fall, I found a spot not far off the trail that would do for camping. A

steep pull up the hill for 30 feet brought one out to a flat stone ledge

overlooking the trail. Andra and I threw down our packs and began munching

on snacks while studying the trees and rocks on the opposite side of the

steep canyon. Andra

and I made our way downstream as others filed into the rock flat below

the falls. Leaf-covered rocks lined the creek, creating a delicious dichotomy

of yellow and red speckles on black rock. The trail continued downhill

through a deep canyon, with walls much to steep to camp on or climb up.

Nothing to do but walk on. At the confluence of the Jones Run and Doyles

River, we fanned out to find a flat spot of ground to sleep on, but found

nothing except bramble-covered slopes under imposing oak trees. In retrospect,

it wasn’t too bad, but at the time we felt we could do better. Maybe it

was just that I wasn’t quite ready to stop the sightseeing for the evening

yet. We started up the Doyles River Trail, a steep and rocky path leading

uphill along the south side of Doyles River. Two magnificent falls stretch

out over a section of the stream, and I regret we had so little time to

dally at them, but darkness was approaching fast. Just uphill of the upper

fall, I found a spot not far off the trail that would do for camping. A

steep pull up the hill for 30 feet brought one out to a flat stone ledge

overlooking the trail. Andra and I threw down our packs and began munching

on snacks while studying the trees and rocks on the opposite side of the

steep canyon.

“That’s an interesting

plant,” said Andra, pointing to a length of Virginia Creeper meandering

along the rock at our feet.

“Virginia Creeper,”

I said, and pointing across the stream to the opposite wall of the canyon,

100 yards away, “Do you see that spike of red? That’s a dead tree trunk

covered with Virginia Creeper.”

“Very cool.”

At that moment, a giant

black bear walked right behind the red spike. We saw it at the same time.

I immediately imagined that the scent of my hickory-smoked beef jerky was

wafting on the down canyon breeze and had been picked up by a cranky old

bear who was coming for it. This is just what he seemed to be doing, as

he ambled at a moderate pace straight at us. We leapt to our feet and watched

his progress in silence. When he got below the canopy of trees in the creek

bottom, we grew very tense, and when I was sure I saw movement below us

on the trail, I sounded the “move-out” alarm. We hopped back down to the

trail, where two hikers were just strolling up. I told them about the bear,

and they seemed unconcerned. Maybe I was overestimating this bear thing.

I relaxed a little, noted that no bear had yet attacked, and we set out

up the trail, unwilling to consider staying at our great spot above the

creek. As we put some distance between us and the bear, I began to think

that it was pretty nifty to spot a bear in the woods. It was only the second

time it had ever happened, the first being a black bear in Redwoods National

Park the year before.

Not much further up

the trail, a very old forest road crosses Doyles River. Stonewall Jackson’s

Brigade used this very road to cross the Blue Ridge in 1862. Once again,

that sense of history seeped through me, and I felt the age of the rocks

piled along the foundation of the road grade. The current use of the road

is for fire-crew access. The road splits not far from Doyles River, with

the original grade splitting off uphill. It is little-used, covered with

trees and shrubs, and is almost indistinguishable except for the line of

piled rocks on the downhill edge that leveled the grade. We hiked along

the newer road to the northeast, searching for a spot to camp. We found

it about 200 yards down the road, well uphill from the river. The bank

of the road on the uphill side leveled out after 20 feet or so, and among

tall oaks on a forest floor of leaves, we set up the tent. The clouds had

vanished, but the sun was going down, and it was too dark to cook. We ate

peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, then packed up the food into the tent

bag. We hung the food from a dead tree about 50 yards from camp on the

other side of the road. It was dark at 7:30.

As we lay in the tent,

hot in the humid air, insects droned by the thousands in the trees above.

Acorns fell from the trees and crashed into the bed of crisp leaves on

the ground, while unknown cracks and creeks seemed to germinate from all

around. Such noise! Unlike the still and quiet alpine woods, this forest

was crawling with activity at night. I escorted two large spiders out of

the tent as I settled in. We both read by flashlight for 10 pages, then

I went to sleep around 8:30. I noticed Andra’s light was still on every

time I turned over for quite awhile. I decided we should hike harder the

next day.

At

10:30 PM, I awoke to the sound of loud wood knocking coming from the general

direction of the food-tree. Loud knocks sounding like someone lazily swinging

a 2x4 against a hollow tree created images of a black bear pawing his way

up the tree in search of that fantastic jerky smell. I lay on my side listening

for awhile, then sat up to listen better. The moon had come out, and was

casting silhouettes of leaves on the tent fabric. The insects had quieted

down. The banging, scraping and knocking continued for 20 minutes, after

which things got very quiet. I could just imagine a bear quietly devouring

our week’s food, finding special enjoyment in the cache of peanut butter.

Even worse, I could imagine that a week’s worth of food wouldn’t do much

to satisfy a bear, and if he liked what he had from the bag that smelled

like tent, maybe he’d go check out that tent that smelled like tent. I

sat, still as stone, for almost 2 hours listening to the sounds of the

woods, and trying to decide how much my scented deodorant had worn off

during the hike. Just as I was sure a sufficiently-long interval of silence

had elapsed, I would hear a suspicious-sounding shuffle of leaves, or twig-crack

nearby. From the comfort of your computer, you may feel that such anxiousness

was unfounded. Let me hear you say the same thing after spending a night

in the woods with known bear activity. A primal human sense awakens in

the darkness of the night when the thought of predators enters one’s mind.

It is not fear, but simply an alertness that transcends reason. Andra,

who had been snoozing soundly the entire time, woke up and asked me what

I was doing. I told her the situation. Her opinion was that no bear would

hang around in one spot for this long, and he wasn’t going to come back

at 4AM to revisit. I agreed, and after awhile, we fell asleep. Ironically

I heard the footsteps just around 4AM. Loud, crunching, shuffling footsteps,

seemingly inches away. I was, and am still, sure that a bear was

investigating our little tent in the woods. I whispered to Andra, :”Wake

up! Wake up!” and as she awoke to my loud whisper, she heard the bear scramble

in surprise away from the tent, crashing through the underbrush, sounding

like an elephant. That kept us awake for about half an hour. We can laugh

about it now. At

10:30 PM, I awoke to the sound of loud wood knocking coming from the general

direction of the food-tree. Loud knocks sounding like someone lazily swinging

a 2x4 against a hollow tree created images of a black bear pawing his way

up the tree in search of that fantastic jerky smell. I lay on my side listening

for awhile, then sat up to listen better. The moon had come out, and was

casting silhouettes of leaves on the tent fabric. The insects had quieted

down. The banging, scraping and knocking continued for 20 minutes, after

which things got very quiet. I could just imagine a bear quietly devouring

our week’s food, finding special enjoyment in the cache of peanut butter.

Even worse, I could imagine that a week’s worth of food wouldn’t do much

to satisfy a bear, and if he liked what he had from the bag that smelled

like tent, maybe he’d go check out that tent that smelled like tent. I

sat, still as stone, for almost 2 hours listening to the sounds of the

woods, and trying to decide how much my scented deodorant had worn off

during the hike. Just as I was sure a sufficiently-long interval of silence

had elapsed, I would hear a suspicious-sounding shuffle of leaves, or twig-crack

nearby. From the comfort of your computer, you may feel that such anxiousness

was unfounded. Let me hear you say the same thing after spending a night

in the woods with known bear activity. A primal human sense awakens in

the darkness of the night when the thought of predators enters one’s mind.

It is not fear, but simply an alertness that transcends reason. Andra,

who had been snoozing soundly the entire time, woke up and asked me what

I was doing. I told her the situation. Her opinion was that no bear would

hang around in one spot for this long, and he wasn’t going to come back

at 4AM to revisit. I agreed, and after awhile, we fell asleep. Ironically

I heard the footsteps just around 4AM. Loud, crunching, shuffling footsteps,

seemingly inches away. I was, and am still, sure that a bear was

investigating our little tent in the woods. I whispered to Andra, :”Wake

up! Wake up!” and as she awoke to my loud whisper, she heard the bear scramble

in surprise away from the tent, crashing through the underbrush, sounding

like an elephant. That kept us awake for about half an hour. We can laugh

about it now.

|

After

two days of driving around Charlottesville, Virginia, in between a rehearsal

dinner on Friday night and an evening outdoor wedding at a pastoral vineyard

near Earlysville on Saturday, we steered the rented Saturn L200 into the

South entrance of Shenandoah National Park at Waynesboro. I was beginning

to become dangerously fond of the L200, as it completely out-classed my

Saturn SL2 at home. It was 10:00 Sunday morning. Intentionally, we had

purchased a James Taylor CD for the purpose of imprinting our experience

on the music. I find the best way to remember anything is to hear the music

associated with it. For example, Def Leopard tunes make me recall those

awkward days of the 6th grade. To this day, I hate Def Leopard. Thus, the

formerly unheard James Taylor became the official balladeer of this trip.

“In my mind I’m going to Carolina.” To a western boy like me, Virginia’s

about the same thing.

After

two days of driving around Charlottesville, Virginia, in between a rehearsal

dinner on Friday night and an evening outdoor wedding at a pastoral vineyard

near Earlysville on Saturday, we steered the rented Saturn L200 into the

South entrance of Shenandoah National Park at Waynesboro. I was beginning

to become dangerously fond of the L200, as it completely out-classed my

Saturn SL2 at home. It was 10:00 Sunday morning. Intentionally, we had

purchased a James Taylor CD for the purpose of imprinting our experience

on the music. I find the best way to remember anything is to hear the music

associated with it. For example, Def Leopard tunes make me recall those

awkward days of the 6th grade. To this day, I hate Def Leopard. Thus, the

formerly unheard James Taylor became the official balladeer of this trip.

“In my mind I’m going to Carolina.” To a western boy like me, Virginia’s

about the same thing.

It’s

always hard to match those first few minutes cruising down a sun-dappled

National Park road after exiting the super-beltway, on which your car is

herded along by the sheer momentum of a thousand others at 80 mph. Sunshine

streamed through the myriad colors of hardwood leaves in the crisp, October

morning air. Red and orange oaks, blazing yellow hickory and tenaciously

green tulip trees, barely frosted with yellow, lined Skyline Drive, casually

leading us north along the crest of the storied Blue Ridge Mountain. The

thin river of dark pavement curved and streamed around rock walls and through

a forest so dense at times I could see no more than 10 feet into its depths

before my vision grew confused at the jumble of shapes, colors and textures.

For the automotive-tourist, Skyline Drive is perfect. Dozens of vehicle

pullouts line the main road on both sides, affording red-blooded Americans

the satisfying option of “seeing” the park without ever getting out of

the car. Hell, we observed some folks who wouldn’t even put their car in

park before cruising on down the road. Now THAT’S entertainment! We enjoyed

the views from several pullouts along the way. Each one, and a significant

portion of the road through the park, was contained by a rock retainer

wall built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. Being so close

to Washington DC, Shenandoah was naturally a great spot for FDR to demonstrate

the utility of the CCC.

It’s

always hard to match those first few minutes cruising down a sun-dappled

National Park road after exiting the super-beltway, on which your car is

herded along by the sheer momentum of a thousand others at 80 mph. Sunshine

streamed through the myriad colors of hardwood leaves in the crisp, October

morning air. Red and orange oaks, blazing yellow hickory and tenaciously

green tulip trees, barely frosted with yellow, lined Skyline Drive, casually

leading us north along the crest of the storied Blue Ridge Mountain. The

thin river of dark pavement curved and streamed around rock walls and through

a forest so dense at times I could see no more than 10 feet into its depths

before my vision grew confused at the jumble of shapes, colors and textures.

For the automotive-tourist, Skyline Drive is perfect. Dozens of vehicle

pullouts line the main road on both sides, affording red-blooded Americans

the satisfying option of “seeing” the park without ever getting out of

the car. Hell, we observed some folks who wouldn’t even put their car in

park before cruising on down the road. Now THAT’S entertainment! We enjoyed

the views from several pullouts along the way. Each one, and a significant

portion of the road through the park, was contained by a rock retainer

wall built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. Being so close

to Washington DC, Shenandoah was naturally a great spot for FDR to demonstrate

the utility of the CCC.

quietly

stalking deer in the dense underbrush. A vision of an early pioneer hunting

rabbits popped into my head. The history of the place was palpable. Ditto

for the moisture. The humid air allowed no sweat to dry, and I constantly

wiped my brow as I walked downhill. I tried to imagine what kind of sticky

mugginess enveloped this place in August, and failed. As I neared the spot

where I left Andra, I turned off the trail and heard her whistle from 20

yards away. The woods were so thick, I couldn’t see her, but followed the

sound right to her. We sat in the leaves and I told her about the grand

sight she missed, and the chestnut tree. We listened to folks hike through

the leaves on the nearby trail.

quietly

stalking deer in the dense underbrush. A vision of an early pioneer hunting

rabbits popped into my head. The history of the place was palpable. Ditto

for the moisture. The humid air allowed no sweat to dry, and I constantly

wiped my brow as I walked downhill. I tried to imagine what kind of sticky

mugginess enveloped this place in August, and failed. As I neared the spot

where I left Andra, I turned off the trail and heard her whistle from 20

yards away. The woods were so thick, I couldn’t see her, but followed the

sound right to her. We sat in the leaves and I told her about the grand

sight she missed, and the chestnut tree. We listened to folks hike through

the leaves on the nearby trail.

Andra

and I made our way downstream as others filed into the rock flat below

the falls. Leaf-covered rocks lined the creek, creating a delicious dichotomy

of yellow and red speckles on black rock. The trail continued downhill

through a deep canyon, with walls much to steep to camp on or climb up.

Nothing to do but walk on. At the confluence of the Jones Run and Doyles

River, we fanned out to find a flat spot of ground to sleep on, but found

nothing except bramble-covered slopes under imposing oak trees. In retrospect,

it wasn’t too bad, but at the time we felt we could do better. Maybe it

was just that I wasn’t quite ready to stop the sightseeing for the evening

yet. We started up the Doyles River Trail, a steep and rocky path leading

uphill along the south side of Doyles River. Two magnificent falls stretch

out over a section of the stream, and I regret we had so little time to

dally at them, but darkness was approaching fast. Just uphill of the upper

fall, I found a spot not far off the trail that would do for camping. A

steep pull up the hill for 30 feet brought one out to a flat stone ledge

overlooking the trail. Andra and I threw down our packs and began munching

on snacks while studying the trees and rocks on the opposite side of the

steep canyon.

Andra

and I made our way downstream as others filed into the rock flat below

the falls. Leaf-covered rocks lined the creek, creating a delicious dichotomy

of yellow and red speckles on black rock. The trail continued downhill

through a deep canyon, with walls much to steep to camp on or climb up.

Nothing to do but walk on. At the confluence of the Jones Run and Doyles

River, we fanned out to find a flat spot of ground to sleep on, but found

nothing except bramble-covered slopes under imposing oak trees. In retrospect,

it wasn’t too bad, but at the time we felt we could do better. Maybe it

was just that I wasn’t quite ready to stop the sightseeing for the evening

yet. We started up the Doyles River Trail, a steep and rocky path leading

uphill along the south side of Doyles River. Two magnificent falls stretch

out over a section of the stream, and I regret we had so little time to

dally at them, but darkness was approaching fast. Just uphill of the upper

fall, I found a spot not far off the trail that would do for camping. A

steep pull up the hill for 30 feet brought one out to a flat stone ledge

overlooking the trail. Andra and I threw down our packs and began munching

on snacks while studying the trees and rocks on the opposite side of the

steep canyon.

At

10:30 PM, I awoke to the sound of loud wood knocking coming from the general

direction of the food-tree. Loud knocks sounding like someone lazily swinging

a 2x4 against a hollow tree created images of a black bear pawing his way

up the tree in search of that fantastic jerky smell. I lay on my side listening

for awhile, then sat up to listen better. The moon had come out, and was

casting silhouettes of leaves on the tent fabric. The insects had quieted

down. The banging, scraping and knocking continued for 20 minutes, after

which things got very quiet. I could just imagine a bear quietly devouring

our week’s food, finding special enjoyment in the cache of peanut butter.

Even worse, I could imagine that a week’s worth of food wouldn’t do much

to satisfy a bear, and if he liked what he had from the bag that smelled

like tent, maybe he’d go check out that tent that smelled like tent. I

sat, still as stone, for almost 2 hours listening to the sounds of the

woods, and trying to decide how much my scented deodorant had worn off

during the hike. Just as I was sure a sufficiently-long interval of silence

had elapsed, I would hear a suspicious-sounding shuffle of leaves, or twig-crack

nearby. From the comfort of your computer, you may feel that such anxiousness

was unfounded. Let me hear you say the same thing after spending a night

in the woods with known bear activity. A primal human sense awakens in

the darkness of the night when the thought of predators enters one’s mind.

It is not fear, but simply an alertness that transcends reason. Andra,

who had been snoozing soundly the entire time, woke up and asked me what

I was doing. I told her the situation. Her opinion was that no bear would

hang around in one spot for this long, and he wasn’t going to come back

at 4AM to revisit. I agreed, and after awhile, we fell asleep. Ironically

I heard the footsteps just around 4AM. Loud, crunching, shuffling footsteps,

seemingly inches away. I was, and am still, sure that a bear was

investigating our little tent in the woods. I whispered to Andra, :”Wake

up! Wake up!” and as she awoke to my loud whisper, she heard the bear scramble

in surprise away from the tent, crashing through the underbrush, sounding

like an elephant. That kept us awake for about half an hour. We can laugh

about it now.

At

10:30 PM, I awoke to the sound of loud wood knocking coming from the general

direction of the food-tree. Loud knocks sounding like someone lazily swinging

a 2x4 against a hollow tree created images of a black bear pawing his way

up the tree in search of that fantastic jerky smell. I lay on my side listening

for awhile, then sat up to listen better. The moon had come out, and was

casting silhouettes of leaves on the tent fabric. The insects had quieted

down. The banging, scraping and knocking continued for 20 minutes, after

which things got very quiet. I could just imagine a bear quietly devouring

our week’s food, finding special enjoyment in the cache of peanut butter.

Even worse, I could imagine that a week’s worth of food wouldn’t do much

to satisfy a bear, and if he liked what he had from the bag that smelled

like tent, maybe he’d go check out that tent that smelled like tent. I

sat, still as stone, for almost 2 hours listening to the sounds of the

woods, and trying to decide how much my scented deodorant had worn off

during the hike. Just as I was sure a sufficiently-long interval of silence

had elapsed, I would hear a suspicious-sounding shuffle of leaves, or twig-crack

nearby. From the comfort of your computer, you may feel that such anxiousness

was unfounded. Let me hear you say the same thing after spending a night

in the woods with known bear activity. A primal human sense awakens in

the darkness of the night when the thought of predators enters one’s mind.

It is not fear, but simply an alertness that transcends reason. Andra,

who had been snoozing soundly the entire time, woke up and asked me what

I was doing. I told her the situation. Her opinion was that no bear would

hang around in one spot for this long, and he wasn’t going to come back

at 4AM to revisit. I agreed, and after awhile, we fell asleep. Ironically

I heard the footsteps just around 4AM. Loud, crunching, shuffling footsteps,

seemingly inches away. I was, and am still, sure that a bear was

investigating our little tent in the woods. I whispered to Andra, :”Wake

up! Wake up!” and as she awoke to my loud whisper, she heard the bear scramble

in surprise away from the tent, crashing through the underbrush, sounding

like an elephant. That kept us awake for about half an hour. We can laugh

about it now.