The

location of this canyon will remain secret. All I will say is that it is

in western Colorado. Really, for this narrative, thatís all you need to

know. The September afternoon sunshine rains a fog of deep orange into

my windshield as I head west from Cheyenne, my temporary lodging base and

food storage area. Grasshoppers splatter on the windshield in chaotic,

profusive explosions of color as they perform their swan song in the fading

warmth of the high desert fall. I pull off the freshly-laid blacktop, and

rumble my low-riding Saturn sedan over the gravel lane to a stopping point

just at the very edge of this particular designated wilderness area. Actually,

it is only a wilderness STUDY area, which used to make no difference in

terms of policy until our favorite Texan, GW, took office and decided to

abandon 50 years worth of wilderness study in Utah. Wilderness Study Areas

are just another piece of land that can be drilled or logged, if needed,

to promote the grand ideal of rich people getting richer, widening the

gulf of wealth disparity in this country and around the world. Shameful.

For the moment, however, Colorado WSAs seem to be safe, and the 2 foot

high barbed wire fence seems to hold the dozers at bay. I step out of my

vehicle and shut the door, the slam muted by the dense pinyon/juniper forest

surrounding me on this dry plateau. Silence greets me. Perhaps the distant

call of a raven? Or the wind? Difficult to tell. I set up camp in the waning

light, and brush my teeth with a foaming white The

location of this canyon will remain secret. All I will say is that it is

in western Colorado. Really, for this narrative, thatís all you need to

know. The September afternoon sunshine rains a fog of deep orange into

my windshield as I head west from Cheyenne, my temporary lodging base and

food storage area. Grasshoppers splatter on the windshield in chaotic,

profusive explosions of color as they perform their swan song in the fading

warmth of the high desert fall. I pull off the freshly-laid blacktop, and

rumble my low-riding Saturn sedan over the gravel lane to a stopping point

just at the very edge of this particular designated wilderness area. Actually,

it is only a wilderness STUDY area, which used to make no difference in

terms of policy until our favorite Texan, GW, took office and decided to

abandon 50 years worth of wilderness study in Utah. Wilderness Study Areas

are just another piece of land that can be drilled or logged, if needed,

to promote the grand ideal of rich people getting richer, widening the

gulf of wealth disparity in this country and around the world. Shameful.

For the moment, however, Colorado WSAs seem to be safe, and the 2 foot

high barbed wire fence seems to hold the dozers at bay. I step out of my

vehicle and shut the door, the slam muted by the dense pinyon/juniper forest

surrounding me on this dry plateau. Silence greets me. Perhaps the distant

call of a raven? Or the wind? Difficult to tell. I set up camp in the waning

light, and brush my teeth with a foaming white  cloud

under a pink sky. Not a breath of air stirs. I crawl into my sleeping bag

and admire the evening stars, orange Mars among them, just before I nod

off. cloud

under a pink sky. Not a breath of air stirs. I crawl into my sleeping bag

and admire the evening stars, orange Mars among them, just before I nod

off.

The dawn does not come soon enough to warm my freezing feet and hands

so I dress in the pale light of the coming dawn and hop around trying to

coax blood back into my extremities. The sky turns pink as I pack my rucksack,

and I decide the clear blue sky being unveiled warrants no further delay

for breakfast. Wolfing down a stick of gelled-granola, I shoulder my pack,

laden with water, snacks, camera, tripod and a map, and begin walking north

to the canyon head. Iíve been here three times before, dating back to the

summer I worked for the park in 2001, but Iíve never explored beyond a

mile or so of its length. Today I intend to go the entire way. My boots

sink into the soft sand, after a brief resistance of a shell-like layer

on top. I skirt around the numerous patches of cryptobiotic soil,

trying to stay within the zone of cedar and pine needles, and game trails

made by numerous ungulates. At one point I spot gigantic paw tracks, no

claws. I shouldnít be surprised to see cougar prints, since I know they

live all around here. I glance around, furtively checking the shadows for

any giant mammal stalking me, secretly wishing to actually see one in living

color. What would I do if confronted by a cougar? Throw a stick or take

a photo? Tough call. I hope I get to make that decision someday.

The shallow creek bed of sandstone, smoothed by violent swells of water,

opens up before me through the scattered pinyon pines. It runs east-west,

and I drop downhill through thick mountain mahogany to reach it. I stroll

down the polished rock creek bed to the west, enjoying the wide open avenue

made possible by the solid rock. I  approach

the brink that lies beyond a pool of mosquito-wriggler-filled water. The

drop off is around 70 feet, with a deep undercut carved out over millions

of years. In the glen below, between two steep inclines, is a forest of

boxelder and douglas fir. I fight the urge to test my flying abilities,

and instead walk round the north end of this roadblock and slide my way

through loose gravel down toward the floor below. Cows, I note, have been

here before. I didnít think cows were allowed in wilderness areas. I must

be wrong. As I descend into the dim canyon, the air cools, and I

note that my hands are cold. The steep tallus drops off several feet into

a trickle of water running at the very bottom. The going seems easier there,

so I let my body fly down into the soft creek bed, filled with sand instead

of rock. I crouch as I walk under low-hanging boxelder branches, and I

gingerly push aside the long, spiked tentacles of wild rose. Fallen logs

and debris clog the route, and I clamor about trying to get around them.

On both sides, loose sand and gravel slopes rise steeply up for 30 feet.

On the right, it then levels off and follows a gentle incline back to the

plateau, but on the left, a sheer rock wall rises up a hundred feet to

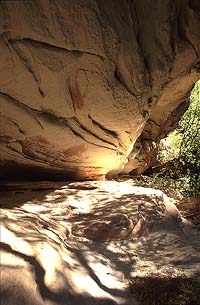

the plateau. I spot a cave, and investigate, visions of giant cougars dancing

in my head. The cave mouth is wide, and the room created by the massive

overhang does not widen, but instead narrows as it retreats into the mountain,

ending some thirty feet beyond the wall-face in a tiny crack that goes

back even further. I note that the sand, even in the protected spot, has

no footprints. I relish the fantasy that I am the first person in a decade

to enter this cave. approach

the brink that lies beyond a pool of mosquito-wriggler-filled water. The

drop off is around 70 feet, with a deep undercut carved out over millions

of years. In the glen below, between two steep inclines, is a forest of

boxelder and douglas fir. I fight the urge to test my flying abilities,

and instead walk round the north end of this roadblock and slide my way

through loose gravel down toward the floor below. Cows, I note, have been

here before. I didnít think cows were allowed in wilderness areas. I must

be wrong. As I descend into the dim canyon, the air cools, and I

note that my hands are cold. The steep tallus drops off several feet into

a trickle of water running at the very bottom. The going seems easier there,

so I let my body fly down into the soft creek bed, filled with sand instead

of rock. I crouch as I walk under low-hanging boxelder branches, and I

gingerly push aside the long, spiked tentacles of wild rose. Fallen logs

and debris clog the route, and I clamor about trying to get around them.

On both sides, loose sand and gravel slopes rise steeply up for 30 feet.

On the right, it then levels off and follows a gentle incline back to the

plateau, but on the left, a sheer rock wall rises up a hundred feet to

the plateau. I spot a cave, and investigate, visions of giant cougars dancing

in my head. The cave mouth is wide, and the room created by the massive

overhang does not widen, but instead narrows as it retreats into the mountain,

ending some thirty feet beyond the wall-face in a tiny crack that goes

back even further. I note that the sand, even in the protected spot, has

no footprints. I relish the fantasy that I am the first person in a decade

to enter this cave.

The canyon widens just a bit, and opens up as rock replaces the sandy

bottom. Cascades and short drop-offs mark the way, and I am careful not

to slip on the mossy sandstone. The sky is brilliant blue overhead, and

not a  cloud

in sight. I remind myself to be aware of clouds that might bring rain,

that might bring a ferocious wall of water down this canyon. Luckily it

is not monsoon season. I finally reach the spot Iíve longed for, a thin,

narrow slot canyon with walls so vertical and smooth that only an animal

with wings could get out. Thousands of thin multi-colored bands in shades

ranging from red to white line the walls horizontally, waving and sweeping

in a hypnotic pattern of geology. I hold my hands out and let my fingers

graze the gritty walls as I walk slowly along. The canyon curls and weaves,

such that at any given time I can not see more than 5 feet ahead or behind.

For 50 or 60 feet it keeps up, until an 8-foot drop-off into a deep pool

of scummy water ends my reverie. I backtrack to where the slope is manageable,

and pull myself out to the right where I can go around the drop-off in

the canyon, and re-enter downstream. The sun hits me as I ascend up onto

the south-facing slope and it feels wonderful. I don my sunglasses as I

squint in the blinding glare off the yellow sand and rock. My boots become

dusty with the red, yellow and orange hues of each passing geologic layer.

The loose sand delays my progress, for every step I take, I slide back

one. Small prickly pear cactus, grouped in large cactus cities, help

determine my route. It is difficult to avoid the cryptobiotic layer, and

when I must cross, I take large steps, and walk on tip-toes to minimize

my footprints. Eventually, I reach a side canyon shallow enough to lead

me gently back into the main attraction. I first walk upstream, following

the same wonderful thin slot as before, until I reach the fetid pool of

water which stymied me to begin with. I turn around and walk down-canyon,

stopping to explore a short side canyon to the south that ends in a box

after two tight curves and steep, sandy climb. The slot becomes cloud

in sight. I remind myself to be aware of clouds that might bring rain,

that might bring a ferocious wall of water down this canyon. Luckily it

is not monsoon season. I finally reach the spot Iíve longed for, a thin,

narrow slot canyon with walls so vertical and smooth that only an animal

with wings could get out. Thousands of thin multi-colored bands in shades

ranging from red to white line the walls horizontally, waving and sweeping

in a hypnotic pattern of geology. I hold my hands out and let my fingers

graze the gritty walls as I walk slowly along. The canyon curls and weaves,

such that at any given time I can not see more than 5 feet ahead or behind.

For 50 or 60 feet it keeps up, until an 8-foot drop-off into a deep pool

of scummy water ends my reverie. I backtrack to where the slope is manageable,

and pull myself out to the right where I can go around the drop-off in

the canyon, and re-enter downstream. The sun hits me as I ascend up onto

the south-facing slope and it feels wonderful. I don my sunglasses as I

squint in the blinding glare off the yellow sand and rock. My boots become

dusty with the red, yellow and orange hues of each passing geologic layer.

The loose sand delays my progress, for every step I take, I slide back

one. Small prickly pear cactus, grouped in large cactus cities, help

determine my route. It is difficult to avoid the cryptobiotic layer, and

when I must cross, I take large steps, and walk on tip-toes to minimize

my footprints. Eventually, I reach a side canyon shallow enough to lead

me gently back into the main attraction. I first walk upstream, following

the same wonderful thin slot as before, until I reach the fetid pool of

water which stymied me to begin with. I turn around and walk down-canyon,

stopping to explore a short side canyon to the south that ends in a box

after two tight curves and steep, sandy climb. The slot becomes  taller,

and a little wider, to about 8 feet across. Sunlight splashes on the south

face of the upper reaches of the wall. After less than 1/8 mile, my route

is blocked here, too, by a drop-off too severe to attempt by myself. I

back up, and take a tributary up the south wall this time to explore further

downstream. taller,

and a little wider, to about 8 feet across. Sunlight splashes on the south

face of the upper reaches of the wall. After less than 1/8 mile, my route

is blocked here, too, by a drop-off too severe to attempt by myself. I

back up, and take a tributary up the south wall this time to explore further

downstream.

On this side of the canyon, shaded a significant portion of the year

by the cliff immediately to the south, the pinyons and junipers grow taller

and thicker than on the plateau top. I weave among them, trying to stay

close enough to the canyon rim to see any possible descents. I follow one

promising tributary down, only to find that it drops off 15 feet. Like

a puzzle, the canyon taunts me with a gentle graded trail in its depths,

with no way to reach it.

In the sun, between patches of pinyon, I can feel my skin drying. The

inside of my nostrils grow dry and my lips crack slightly in the hot air

I suck in through my mouth when my breathing grows too intense. The air

is still and quite. The sky is depthless. I take crunching steps through

brush and over gravel, confident that my sounds are heard by no human.

In the silence, I feel the lizards basking.

I finally arrive at a possible descent. I slide down halfway on my heels,

ready to fall onto my butt should the sliding get out of control. I pause

at a thin ledge, an inch wide, and contemplate the likelihood of my making

it back up. My feet make the decision for me, and roll over the ledge

to continue the slow slide down the smooth, sloping rock. My hands grab

at prickly shrubs along the way. In the cool shade of the canyon

crevice again, I walk up-canyon to explore the explorable, then, stymied

by overhanging ledges, return and explore down-canyon as far as possible.

What greets me is one of the great surprises of my life. The quaint narrow

slot becomes a gaping fissure, a hundred feet deep, and I am in the bottom.

Each step takes me lower, even as the surrounding cliffs rise higher. Giant

boulders, wedged firmly into place by ancient, wrathful storms, provide

stepping stones for the descent. Finally, after weaving through perhaps

50-60 feet of the most gorgeous ribbed-wall sandstone Iíve ever seen, the

path ends. A drop-off so deep I canít see the bottom abruptly stops my

advance. The crack twists as it  slopes

downward almost vertically so that I canít see anything beyond 25 feet.

I throw a pebble down and listen as it clanks and cracks between the walls

for 3 full seconds before the sound ends. A canvas tow strap, securely

looped around a large boulder and having a carabineer at the end near the

drop-off attests to previous explorations. How many people have seen this?

Perhaps not more than a dozen. Wonderful. No maps show this location. No

guides talk about it. It is not for me to reveal its secret. Besides, there

can be no greater reward than the unexpected surprise through exploration. slopes

downward almost vertically so that I canít see anything beyond 25 feet.

I throw a pebble down and listen as it clanks and cracks between the walls

for 3 full seconds before the sound ends. A canvas tow strap, securely

looped around a large boulder and having a carabineer at the end near the

drop-off attests to previous explorations. How many people have seen this?

Perhaps not more than a dozen. Wonderful. No maps show this location. No

guides talk about it. It is not for me to reveal its secret. Besides, there

can be no greater reward than the unexpected surprise through exploration.

I retreat from the frightful drop-off and scramble up the steep wall

of the canyon to get down-stream. I follow the ridgeline, which leads me

away from the canyon with each step. I find an old, faint jeep track, and

follow it in the same direction as the canyon winds. After a mile, it intersects

the canyon, at this point only a sandy wash. I follow the slice in the

earth through dense thickets of willow, using my arms to shield my face

from the stiff branches. Upstream I go, hoping to reach the bottom of the

drop-off I was looking down upon an hour before. The sandy wash is much

more sinuous than the canyon, and it takes 100 steps to get only 5 steps

closer to my destination. I try once to leave the winding path carved

by water, and walk a straight line to the canyon walls, visible close by.

This lasts only a minute, as I discover that the willows are virtually

impossible to wade through. In only a few minutes, the canyon widens, and

deepens. I stop and sip water and revel in the silence. My boots sink in

the soft, dry sand. The sandy wash becomes a rocky draw, then a smooth,

sandstone canyon once again. Thick stands of willows are replaced by occasional

junipers, somehow managing to survive in a crack of solid rock. Around

a corner, a dead end greets me. A boulder the size of a kitchen table is

wedged in a steep chute, and is round enough to prevent any handholds.

I am able to use my legs and arms to climb vertically up the canyon and

peer over the boulder. I see a smooth, sandy path running between two vertical

walls for 25 feet before curving and disappearing. I know the wonderful

drop-off is a destination I wonít reach. Turning back, I retrace my steps

for 50  feet,

then spend a half hour in the shade of the canyon, seated on a rounded

bench of sandstone, storing up the quiet and peacefulness of this utterly

remote canyon. My feet lead me back over my own footprints in the sand,

up the jeep track and back down into the deepest part of the canyon, which

I desire to see once again. I spend several minutes watching the rocks,

snapping photos and feeling small in the presence of such enormous mass. feet,

then spend a half hour in the shade of the canyon, seated on a rounded

bench of sandstone, storing up the quiet and peacefulness of this utterly

remote canyon. My feet lead me back over my own footprints in the sand,

up the jeep track and back down into the deepest part of the canyon, which

I desire to see once again. I spend several minutes watching the rocks,

snapping photos and feeling small in the presence of such enormous mass.

With few deviations, I retrace my path all the way to the mouth of the

canyon and camp near it that night.

A new day, a new canyon. This one lies south of the first. I begin with

a steep hike down a sandy and shady slope, weaving in between junipers,

cactus and pinyons. There is no help to be had from any map with the winding,

twisting rocks and drop-offs. I meet ledge after ledge that are too steep

to climb down. Each one is tackled by patiently probing laterally until

a descent becomes possible. One by one, I drop down from ledge to ledge

to the bottom of the canyon. I reach it before I expect to, and am pleasantly

surprised to find myself on level ground, in a smooth, rounded sandstone

slot. I grin at my first site, and decide to explore up-canyon first.

Hoping to find my way back up the tortuous route I pioneered to the bottom,

I stack 5 stones in the middle of the creek bed to mark the exit.

How can I adequately relate the pleasure of every foot of perfect sandstone

canyon? I donít think it can be described for full appreciation. I walked

up the canyon, skirting pools of water and using the friction of my boot

soles to carry me up steep ramps. Finally, inevitably, I reach a point

too steep to attempt, and decide to turn back. Following the canyon

downstream, I find a particular narrow passage that is one of the best

of the trip. I follow its twisting path down a gentle chute until the end

of the road wells up in the form of a 100 foot drop-off into a  boxelder

forest below. I manage to backtrack 30 feet and swing up out of the slot

and explore the rim. I search for a route down, but a solid cliff face

provides no ramps or paths. I sit on a rock bench under a gnarled juniper,

snacking and drinking and watching the gaping canyon open before me, with

no way to get into it. boxelder

forest below. I manage to backtrack 30 feet and swing up out of the slot

and explore the rim. I search for a route down, but a solid cliff face

provides no ramps or paths. I sit on a rock bench under a gnarled juniper,

snacking and drinking and watching the gaping canyon open before me, with

no way to get into it.

I walk through cactus and bunchgrass to the next canyon, not more than

1/10 mile to the south. Here, too, a steep cliff prohibits descent. One

would have to detour several miles to reach the bottom. I am not prepared

to do so. Instead, I make my way slowly back towards camp by a twisting

and varied route, stopping often to sit and enjoy everything about the

canyon. All too soon, I find myself on flat ground on the plateau overlooking

the menagerie of curved rock. I hop in my car and drive towards home. |