| March 19 2004

It is springtime, and I find myself once again happily, dreamily, religiously,

lacing up my lug-sole leather boots at the open trunk of my extra-fuel-efficient

Saturn. The back and driverís side doors are open, seats littered with

the gear of hiking souls..a backpack, extra socks, water in multiple bottles

so old the lettering on the outside has been worn away and the once-transparent

plastic is now only barely-translucent, peanuts, a banana. Something oddly

familiar and comforting about the generic sunscreen lotion I slather over

my neck reminds me of desert silence, sandy trails and sunburns. I stuff

all items within reach into the various pockets of my blue backpack, except

for the pocket with the hopelessly snagged zipper, and shoulder it. I grab

my trusty 35-mm camera and sling it over my neck and shoulder. Doors slam,

the trunk snaps shut. Walking away from my car I notice that among a row

of 10 vehicles, mine is the only car among a mob of trucks, jeeps and gargantuan

urban assault vehicles. It seems as if my car made it to the trailhead

just as well as that high clearance 4x4 over there.

The trailhead seems busy, and I soon learn that most of the occupants

of the vehicles in the dusty gravel lot are not actually on the trail at

all, but milling about at one of the low water crossings nearby, splashing

and wading in the 8 murky inches of the Prairie Dog Fork of the Red River.

I hike quickly to leave behind the dull roar of the congregation and step

onto the smooth packed earth of the Lighthouse Trail. This is in Palo Duro

Canyon, which Iím told is the United Stateís second largest canyon. By

whose authority or measuring guidelines that assertion is made I know not.

It could be complete fiction concocted by the overworked volunteer staff

at the entrance gate. After all, this is only a state park. The largest

in Texas, yes, in the state that prides itself in doing everything bigger

than anyone else. The state where the stars at night are big and bright.

My home state, to be exact, some time ago.

In 1876, Charles Goodnight led his herd of 2000 steers from New Mexico

into the former Republic of Texas, searching for an ideal spot to settle

down on the unclaimed land of the Panhandle and build his ranch. He found

a choice spot of unusual geology in a deep canyon just south of present-day

Amarillo. It was wide and deep, and had lush stands of grass in it. After

running off the native buffalo that had taken refuge from hide hunters,

he moved his cattle down one of only a few viable entries into the canyon

and set up his ranch there. The natives called the canyon Palo Duro, after

the dense-wooded junipers that grow here. Goodnight set up the JA Ranch

with a British partner, and made lots of money selling beef to hungry New

Yorkers. This is what Iíve read, anyway. I see no sign of cattle as I cruise

along the slightly sloping trail, admiring the bristling expanses of prickly

pear cactus. Mesquite trees line the trail, small, shrub-like forms that

provide no shade. Tufts of brown bunchgrass breakup the expanse of red

soil. Iíve gotten lucky to stop by this place on a gorgeous March afternoon,

with the sky cloudless and the temperature hovering around 80 degrees.

I say hello to a couple of groups of people within a couple hundred

yards of the trailhead. One couple is off the trail, seemingly searching

for birds (the field glasses give it awayÖor else they are disgruntled

snipers looking to plug a campground host). They seem to be in the right

place for bird watching. I notice many types of birds, though Iím not paying

attention to that. In the late afternoon, especially as the sun sinks and

the air cools, the shrubs come alive with the chirping of tiny chickadees.

On the trail, I pass a mother wheeling one of her children in an all-terrain

stroller. Fascinating.

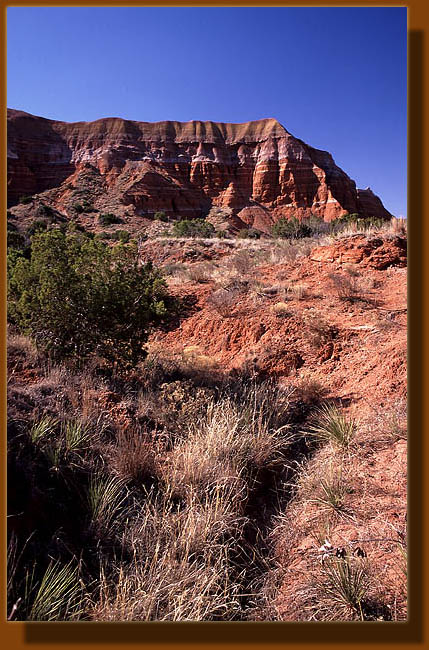

The canyon is said to be named after the hard juniper wood that is found

here, but I think the canyon would have been more aptly named for the red

soil that forms its walls and basin. This is the most striking feature

of the place. Brittle soil walls form buttes and knife-edge ridges in a

labyrinth of sedimentary shapes. As the trail curves around and through

them, I pass through sections where the low sun angle reveals the deep,

sinuous erosion rills by their corresponding ridgesí shadows. In

the distance, the ultimate walls of the canyon rise up some 800 feet, creating

red and orange mosaics in the sunlight. A fleeting thought sprays across

my cerebral cortex: this would be a good time of year to see rattlesnakes.

I pass a man of about 35 with two young red-faced boys, perhaps his

sons. Both boys seem pretty beat, and the man, wearing an extra wide brim

bush hat, encourages them relentlessly. Their course is leading back towards

the trailhead when I pass them by. Will they grow up hating the outdoors

because their enthusiastic dad force-marched them on a 5 mile hike in the

desert in sneakers? I give them a 50-50 chance. Seems to me that a love

for the outdoors is native to the soul, present at birth. I happened to

be born under that lucky star myself, I believe. Terrible camping trips

did nothing to deter me from this life of REI catalogs, topo maps and granola.

Things like stabbing my leg inadvertently into a yucca plant donít bother

me as much as some folks. Thatís fortunate since thatís exactly what I

do three or four times on this walk. The trail is sandy in most places,

and sunk down relative to the surrounding terrain. Giant yucca wait in

ambush along the trail edge, deftly striking out needle-sharp leaves at

me as I pass in shorts, my white pasty legs utterly defenseless. As far

as I can tell from the 8.5 x 11 inch paper map of the park, this is the

longest designated hiking trail at 4.8 miles round trip. This map,

if I may complain, is drawn incorrectly rotated 90 degrees, so that west

is roughly at the top of the paper. This is terribly disorienting to anyone

used to having north at the top.

The air is dry, and after only 45 minutes of hiking I can feel the salt

deposits on my forehead from evaporated sweat. I drink water, though I

donít feel thristy, to ward off dehydration. In the silence of the still

canyon air, I can clearly hear my gulps. It is amazing how quickly the

human body deteriorates when you sit around all winter indoors. When you

first start hiking again in the springtime, muscles seize up, heads ache

and often times the gastrointestinal tract announces an across the board

workersí strike. I tread lightly so as to avoid agitating my bodyís various

components.

I pass by Castle Peak, and the trail veers southwest. A couple of bikers

come gliding down the trail towards me, almost completely silent in the

soft sand. I step aside, nod at them silently and congratulate myself on

my denial of the temptation that had occurred to me only seconds before

to unzip and urinate on the side of the trail. I keep walking, and find

a convenient spot to hide myself from the trail while relieving my bladder

of its insistent pressure. I keep drinking.

The trail passes through dry creek beds multiple times. Some of the

creek channels are very wide and open, while others are narrow and cave-like.

The latter are very cool as I tromp down through the sandy soil, noting

with satisfaction that I am leaving the only footprints. My satisfaction

is shattered as I spy a blue plastic juice bottle discarded in the creek

bed. I pick it up and put it in my pack. There is nowhere to run to escape

your fellow man. The best we can do is indulge the fantasy that we are

the first to arrive at a particular spot on this earth. But it is only

a fantasy.

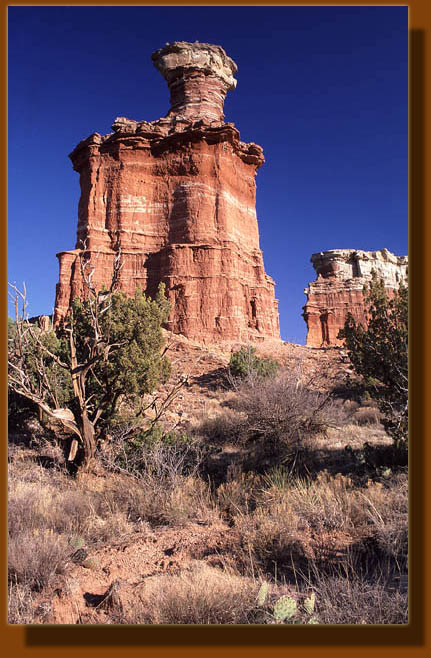

For most of trip, the Lighthouse is plainly visible at the head of the

canyon. This is a distinctively-shaped rock pillar that is the advertised

destination of the trail. Each time I crest a ridge between sections of

the same oxbow creekbed, the Lighthouse is a little bigger. To my left,

a long ridge of crumbling soil provides the entertainment. I keep my eyes

open for roadrunners. Large birds of prey..eagles, hawks, buzzards?..glide

on unseen air currents high overhead, too far up for identification with

the unaided eye. I glance around and find myself walking into another yucca

plant. I wonder which predator keeps the yucca plant from taking over the

world.

The trail is virtually flat for most of the trip, until my feet lead

me finally to the base of the hill whose pinnacle is called the Lighthouse.

Here, a steep ascent is required, although luckily the state park service

has provided handy wooden steps to help you on your way. And a bench halfway

up. No comfort is spared. From a big rock along the way, I learn that Joe

was here. Good thing he let us know. In the shade cast by the hillside,

I ascend quickly and come out onto a flat, juniper-lined trail that leads

to a short plateau immediately in front of the Lighthouse. I sit and wait

on the ledge while an English couple finishes walking up the short trail

from the Lighthouse and passes down the steps. They say a few nice words

to me, which is how I deduce they are English. I adjusted my camera

and snapped pictures of the interesting landmark, then moved in closer

for a better angle.

Snapping more shots of the rock, I hear the unmistakable rambling of

at least two pre-adolescent kids coming up the trail. I hurry to make some

few final adjustments to the camera and snap off a couple more shots before

they arrive. The ledge that holds the Lighthouse drops away on the west

side into a steep canyon, and I follow this canyon rim in a short semicircle

to where I have a full view of the lighthouse and part of the canyon wall.

I sit in the sun and watch the two kids run up the steep slope and plant

their hands on the vertical face of the rock pillar and scream with glee,

"We touched the Lighthouse!" I refrain from touching the Lighthouse, myself,

but indulge in capturing it on film from every angleÖthe adult equivalent

of touching it. The "look but donít touch" threat has finally sunk in.

The kids leave as quickly as they arrive, and two minutes later, I am again

alone with the gleaming red rock. The sun sinks lower, and the red color

intensifies. I walk around both sides, enjoying the shade on the east side,

the warm sun on the west. In the shade, I find a smooth rock to sit

on, where I drink water in single, pleasant gulps, and eat a snack.

I retreat slowly down the hill, stopping and standing at length to admire

the panorama of the canyon fully open before me. Two white T-shirts bob

along the trail far away, heading this way. I pass the bench on the hill

and stand on it. The deepening shadows bring a drama to the shrub-covered

canyon floor. Bright orange slices in the green carpet indicate the cut

of the creekbed. I try to imagine the plight of the natives who took refuge

in this canyon while being hunted down by the US Cavalry in the early 1870ís.

Seems like one could hid forever in here. The cavalry rounded up the tribeís

horses and ran them off, or slaughtered them, according to some sources.

Without their horses, the Comanches surrendered, and acquiesced to go to

the reservation in Oklahoma. As pristine as the canyon seems, the history

of human presence stretches back quite a long time.

I follow the same trail back towards my starting point, past the same

narrow creekbeds and wide channels. I pass the two bobbing white T-shirts,

two teenage girls who refuse to make eye contact with me. I suppose itís

the goatee. It makes me look like my evil twin. Who is, by the way, not

so evil. I pass by a vista where the park service erected an info kiosk

of some sort: a wooden bench beside an information panel tilted toward

the Lighthouse, presumably printed with a short blurb about the geology

of the rock formation. Strangely, I notice the same man with the giant

bush hat with his two young boys at the panel, the boys looking even more

beat than before. Why they were now 2 miles down the trail when they had

been walking towards the parking lot an hour before is a little bit of

a mystery that I ponder. The dad is giving instructions for the boys to

stand on either side of the information panel so he can take their picture.

That looks like fun. I revise my estimate of their liking the outdoors

when they get older to 40-60.

I move on, and the sun begins to rest just on the canyon edge. Minutes

more and it will be gone. In those last 15 minutes, the soil slopes become

alluringly red against the blue sky. I stop and willfully disobey the posted

placards by stepping off the trail. I find myself a few choice vantages

of particularly interesting formations and snap away with my camera. As

I squat, squinting through my eyepiece and adjusting my polarizer, I hear

voices on the trail nearby. I remain quiet in the shrubs as they pass,

the father and his complaining boys. They are far past physically exhausted.

One of them is being carried. The father is trying to explain why they

canít stop and rest. Another revision: 30-70.

I begin to think myself that I must be moving along. No auto campsites

were available to me when I arrived, so I paid for the right to walk out

into the wild and camp wherever I could find a patch of cactus-free turf

that suited me. Strangely, this is no cheaper to do than to camp at a designated

site with running water. Still, at ten bucks, itís a bargain. In order

to find said cactus-free spot prior to the stars lighting up, I feel I

should be moving on. I return to the trail and walk on, quickly, unable

to stop myself from stopping to take pictures of the surrounding soil buttes

every 100 yards or so. I pass the two boys and the father, and say a few

words of encouragement to the two boys.

Minutes after the sun dips below the horizon, I am back at my car. Only

two other vehicles remain. I drive off down south towards pavementís end,

the designated backpacking area. Gotta keep those backpackers contained.

I stop at one of the Retiree-Vehicle "campsites" and use their running

water bathroom and wash the salt from my face. Foolishly, I pass up the

opportunity to wash the salt from my entire body in the free shower room.

I am only thinking of getting to a suitable campsite prior to complete

darkness, so I move on, quickly. I reach the parking lot at the end of

the road, and throw gear into my green frame pack as fast as I can. I shun

the thought of cooking in the dark, and leave my campstove and gas, but

grab a sealed pouch of MRE "Enchilada with beef sauce". Itís Tex-Mex tonight!

Near the car, there is a spigot of water from which I refill my empty

bottle. The water is putrid, and I resolve to use it only in an emergency.

I mentally check that I placed a fresh bottle in my pack. Trails

seem to lead off from the lot every 10 feet. I pick one, and end up just

north of a fairly substantial stream, perhaps the Prairie Dog Fork, Iím

not sure. Overhead, tall cottonwoods provide a canopy in the fading light,

and dense reeds and grasses form short walls on either side of a sandy

trail. Thinking I am the only one backpacking in the area, I am surprised

to see a couple cooking dinner in front of their tent just off the trail.

Good for them. Another couple revisiting the joys of reclusive camping.

I oblige their desires to be left alone and walk silently by, unnoticed,

I believe. Shortly beyond, frantic flapping like that of a sage grouse

erupts from the trees overhead. I look up to notice the biggest damn sage

grouse Iíve ever seen. Then I note that they are turkeys. Wild turkeys,

I suppose. Though one never knows. There seems to be little difference

as far as I can tell between wild and domestic turkeys, unlike your wild

and domestic pigs. Wild turkeys fly off in every direction. I hear a large

turkey turd splat on the ground nearby as itsí former owner takes flight.

The sun is long past set when I strike off the trail up a steep ravine

leading to somewhere that I hope will have less grass and reeds than the

crap Iím walking through now. Up the steep ravine, I carefully wind my

body around sharp yucca leaves. This ravine leads to open expanses of exposed

soil and cryptobiotic covering. Walking in between the heaviest cryptobiotic

patches, I locate a relatively flat spot on soil and proceed to set up

camp in the colorless blue haze of evening. The sky to the east is black,

while the sky to the west still maintains a cheery orange dash. With tent

up, I toss in my gear, and then sit back, take off my shoes, and enjoy

that enchilada with beef sauce. Surprisingly spicy, I wash it down

with my good water, and rinse my hands with the bitter. I decide to finish

with a tasty can of pear halves Iíd been saving, and discover to my dismay

that I left the can opening multi-tool in the blue backpack from the dayhike.

Regretfully, I replace the can of pears into the pack.

Gusty winds blow across my exposed position on the ridge. I can look

out over the entire valley to the walls beyond. As I remove my outer clothes

in the tent, the stars twinkle overhead through the bug-mesh roof. They

really are big and bright at night. I lay down and enjoy the cooling breeze

intermittently flooding through the tent windows. Before long, however,

I grow annoyed at the jingling of the door zippers every time the wind

blows and shakes the tent. I am woken time and again as powerful gusts

bend the tent frame down, and shake the fabric and zippers. Chilled, I

crawl under the sleeping bag but discover throughout the night that it

is difficult to sleep comfortably when covered with salty sweat. Nevertheless,

when dawn comes I feel refreshed, and note that a very heavy dew has formed

during the night. Everything exposed to the sky is soaked.

In the predawn light, I dress and take down the tent. Thoughts of waiting

until the sun is fairly up to dry things out are abandoned, and I pack

up everything wet. Dawn finds me poised on a high bluff over the valley

with my camera trained on the SW side of the canyon, waiting for the light

to get just so before exposing that little strip of coated plastic behind

the camera shutter. The air is still, and very warm for early morning in

March, though perhaps normal for west Texas. When the sun comes up, long

shadows cross the valley floor, and even after 10 minutes, the valley floor

is not lit up. With the gear all packed, I hoist my backpack and try to

find the ravine I ascended in the dark the evening before. I find it, luckily

enough, remembering it for the numerous yucca plants requiring some skill

to get around. At one point, while awkwardly stepping around a yucca, the

soil under my leading foot gives way, and I fall down several feet, landing

with my knee in a cactus plant. I pull back and carefully pull out the

inch-long spines protruding from the skin over my kneecap. Only my kneecap

saved me from being impaled to the bone by the stiff yellow spines. They

leave itching bumps that persist for two weeks. Luckily, this kind of thing

doesnít rile me at all. Part of the fun.

A short walk brings me to my vehicle, covered in a fine layer of dew,

like it just had a good workout at the gym. All the gear is thrown mercilessly

into the trunk, and I drive up the road 1/8 mile to the shower house, where

I indulge in the long-overdue hot shower and shave. I donít know where

they hide the water heater, but itís a nice touch. Another brilliant morning

is above me, blue sky and warm, vibrant air. I slow down for a passing

clique of turkeys, their heads exceedingly grotesque and reptilian in the

full morning light. I was hoping to see roadrunners, but turkeys will have

to do. With no cars on the road, I drive slowly, admiring the last nice

bit of scenery until I get back to Colorado. Passing by the car camp, with

a dozen groups milling about closely-packed picnic tables on a barren plain

no longer than 200 feet, I am reminded why I prefer to backpack. The smell

of woodsmoke and bacon is powerful through my open window. I notice that

the site closest to the road is occupied by the man with the bush hat and

his two boys. At a side road shortly beyond, I get out and take a trail

up a short ways to eat a granola bar for breakfast and guzzle the last

of my good water. Castle Peak lies before me a couple of miles away. I

canít see the trail I took, but I can pick out which buttes and walls it

passes by. The last stop before exiting the park is at the top of the canyon

near the visitorís center where I eat grapefruit while seated on the rim.

The wind is cold up here, as opposed to the warm calm air down below, and

I donít tarry long before exiting the park and returning to the dull, flat

monotony that is the way of life in the Texas Panhandle. |

|