| Location: Dinosaur

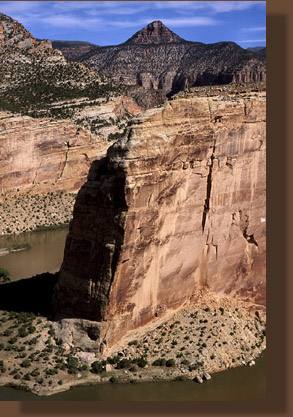

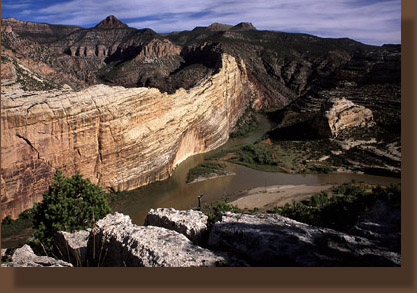

National Monument, Colorado

Maps:1:78K National Geographic Trails Illustrated #220 Dinosaur National Monument; USGS 7.5í Quad: Canyon of Lodore South Access:From Highway 40 near Dinosaur, CO, take the Harpers Corner Rd 23 miles, then turn east onto the Echo Park Rd which leads down through upper Sand Canyon and splits just beyond. Take the left fork that goes to Echo Park, and follow the road to a shaded pullout near petroglyphs along Pool Creek. Park here and walk back up the road and take the faint trail that leads uphill on the east side of the road. Trailhead: NAD83 zone 12 670398e 4486535n Elev: 5195' Fees:None, unless camping Dogs:Not allowed Weather: Recent Conditions Pinpoint Forecast Echo Park is a fantastic place to camp, and a great place to hike as well. Having camped and hiked numerous times within the confines of the sandstone walls of the canyon hasnít diminished my excitement at camping and hiking there again, or the prospect of future trips. Indeed one of the place Iím sure Iíll be visiting regularly into my nineties is Echo Park. Oddly, this place by all rights shouldnít be here, or rather, it should be under hundreds of feet of water. The dam came so close to being built that the director of the National Park Service, Newton Drury, resigned in protest in 1951. Evidence of the dam survey is still in situ at certain areas along the shore in the form of test holes and abandoned ladders so old they have been bleached to the same color of the rock. Larry and I had taken a break from work and spent the week exploring the greater Dinosaur area, hiking canyons, scrambling up dryfalls, threading new trails through sloping pinyon-juniper forests. Some of the time we had great sunny weather, the kind that brings out the full color of the sandstone layers in the cliffs, and some of the time we had cold rains, the kind that make you wish you had a bigger tent so you could sit and read your book rather than laying down to read your book. The trip culminated in a drive down into Echo Park and camping along the south shore, our tents tucked away beneath a sprawling complex of cottonwoods. The river itself was completely hidden from view by virtue of the impenetrable thicket of tamarisk stretching 50 feet thick between campsite and shoreline. Boggy silt and standing water lay among the tamarisk, no doubt contributing to the healthy mosquito population that pestered us to no end. Still, a bad day spent swatting mosquitoes at Echo Park is better than a good day at the office...no contest. Early in the morning, we packed up tents and loaded the cooler into the truck, breakfasting on donuts and coffee in order to speed up departure. This last day was perfect. The temperature was hovering around 80 degrees, the sun was shining, and whispers of clouds graced the sky, with just enough white to make one appreciate the blue. Hopping in the truck, we drove the short distance from the campground, up Pool Creek to the pullout for the petroglyph panel in a narrow section of the canyon. We had discussed with the campground ranger how to access this trail, and I thought I had a good handle on it. This did not, however, mean we found it right away. After 10 minutes of walking along the road and searching for obvious routes, we finally found it, about 100 yards south of the pullout going uphill towards the east. We donned packs, sunglasses and sunscreen and headed uphill through tall grass and over loose, sandy soil. At the top of the short hill, the trail forked. We took the right fork, which turned out to be the unofficial and lesser-traveled route. The thin trail led boldly at first through open grassland dotted with cactus and sagebrush. Occasional junipers provided some dark green contrast to the curing grasses. The trail faded by degrees until I was no longer sure we were even on a trail. In some places it was entirely unclear where the trail was, and we simply walked in a northerly direction towards what we believed was Jenny Lind Rock. I avoided stepping on the delicate cryptobiotic crust whenever possible by sticking to the shade of junipers where the evergreen needles prevented erosion and formation of cryptobiotic crust, but in some places there was no option but to crunch over the black crust, feeling guilty. I pondered why I feel guilty about my four footsteps across cryptobiotic crust when the ranchers donít seem to have a problem letting 200 steers trample the crust for months every year. Nothing against ranching in general, just ranching in this desert climate where all the plants are delicate and hang on by a thread every year. Our northerly route took us gradually uphill into increasingly thick juniper woodland. About an hour after we had begun, we reached the cliffs overlooking Echo Park. Jenny Lind rock is a peninsula of rock thrusting north into the canyon. We were situated on the west side of this peninsula, looking west straight across the airy expanse to Steamboat Rock. We did not hike out to the tip of Jenny Lind, but were contented to go halfway. From our perch we could see the confluence of the muddy Yampa and the green Green, joining together, but staying apart for many hundreds of yards. The distinction in color between the two was clearly visible even as the river rounded the southern tip of Steamboat Rock and meandered northward. Tiny, insignificant cottonwoods dotted the floodplain, and all the details of the campground and boat ramp were laid out before us like a living map, the way a buzzard sees the whole world. Iíve not read any hard accounts of the naming of Jenny Lind rock, but it seems likely it is named after the "Swedish Nightingale", Jenny Lind from NY City, who was apparently quite the singing sensation back in the late 1800ís. Why is a desert plateau named after a NY City singer? The same reason that just upstream lies Cleopatraís Couch, or Outlaw Park, or even Katyís Nipple. Explorers have to name things, and they like to name things uniquely. Obviously, some particular explorer was missing his phonograph collection and missing "The Swedish Nightingale" particularly. Over the course of the next hour, we walked slowly back south along the canyon rim, stopping at intervals to take photographs and eat M&Mís and relax in the warm sunshine on large, flat rocks. We watched a flotilla of rafts and kayaks round the bend on the Yampa, and float slowly on the sluggish current towards the boat ramp. I was reminded of my own float past that very spot 4 years before. When we had reached the boat ramp, it was like surfacing to reality from a wonderful dream. I wasnít happy to see that boat ramp at the time, because it was the first thing in 2 days that reminded me that other humans lurked about. Larry and I discussed the history of Echo Park, how it nearly fell victim to Progress and economic improvement (Yikes!). Three dams were proposed inside the existing boundaries of Dinosaur National Monument in the 1940ís. The largest dam was to be at Echo Park, plugging the Green River and backfilling the Eden before us with water. Other dams were planned for Split Mt downriver and Cross Mt on the Yampa upstream. David Brower made his big splash and made the Sierra Club a household name with his dogged resistance to these dams. By mobilizing public opposition against the dam projects among an increasing segment of the population that placed high value on aesthetics and wilderness, Brower was able to focus attention on the dam projects and ultimately bargained to have those projects rescinded and thus maintained a free flowing river system in Dinosaur National Monument. The final stroke that persuaded the Bureau of Wrecklamation to agree to pulling out of Dinosaur was David Browerís agreement not to pit Sierra Club opposition against a dam in Glen Canyon. David Brower is said to have deeply regretted this decision for the rest of his life. But were it not for Brower, all the dams would likely have been built, and that much more Colorado Plateau canyonland would be inundated for the benefit of fuel merchants, boat dealers and alfalfa farmers. The Sierra Club that is the butt of so many jokes in conservative circles is the same entity that made many of those wonderful calendar scenes possible. Who wants a calendar of "Great Reservoirs of the West"? But how many times have you seen a calendar with a photo of the Grand Canyon, or the Redwoods, or unspoiled beaches free of development? There is no economic benefit from wild land that can compete with the economic benefit of extraction, at least in a short term view. If all that interests you is money, wilderness doesnít make sense. Iím happy that it all makes sense to me. To read biographies of David Brower, you get the sense that if he had it to do over, heíd save Glen Canyon and forsake Dinosaur, assuming he would ever have been able to do that. Anyone who hasnít been to Dinosaur might thus get the impression that the canyons it holds are second rate, and not especially worthy of the commuted sentence that saved them. I canít say how they compare relative to Glen Canyon, since I was born only a few years before it flooded completely, but I can say that nobody who goes there can take the Dinosaur canyons lightly. They are phenomenally beautiful, and I hope they always remain that way. Moving on south along the rim we picked up a well-worn path that wove among the junipers, cutting a neat 10-inch strip of bare soil through the jungle of cryptobiotic crust and bunches of Oryzopsis hymenoides. Clouds increased in the sky, but never blocked it out. These clouds were of the accent type, not the raining type. The air was calm and still on the plateau, and now and again, we could see tiny cartoonish human figures walking painfully slow far down below in the campground. We followed the trail as it retreated from the cliffs and worked its way downhill, intersecting the cliffs over Pool Creek, and then meandering along this wall back to the fork in the trail which we had not taken. From there, one has the first opportunity to get down off the plateau. The entire trip took about 3 hours, with much of that time spent loafing and watching the canyon. We hopped back in the truck, and cruised back uphill to the Yampa Bench road which we cruised east on. I relished the return to a familiar road that, owing to my lack of a high-clearance vehicle, I had not driven since I worked in the park 4 years ago. We stopped at Harding Hole and spent 30 minutes walking along the rim of the Yampa canyon. Not a car or human was in sight. The only sign of civilization was the dirt two track we had driven in on. The air was deathly still, which was very odd for this time of year. Back on the Bench Road, I kept an eye peeled for the turnout that signaled the outlaw hideout in the cliffs above the Yampa that Steve had shown us years before. I did not remember or recognize it it, so we did not stop. As Larry says, "A mind is a terrible thing." I remained dumbfounded for several minutes as we passed through an enormous burn on the east end of the bench near Dry Woman Creek. Thousands of acres of pinyon-juniper forest had been blackened, and whatís worse, only barely blackened, such that almost every tree was still standing, dead, creating a nightmarish landscape of charred, bleached skeleton trees, surrounded by an ocean of annual mustard. If a fire is going to burn up PJ, it might as well incinerate it completely and get it out of the way. We passed by Haystack Rock, and considered hiking out to it, only it

was getting late in the day. The Bench Road led uphill past Thanksgiving

Rock, then back south towards Hwy 40 and home.

|

|