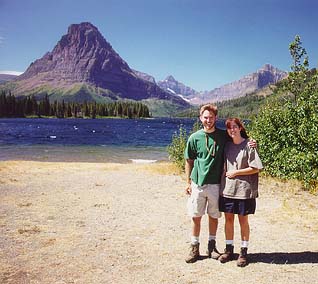

Andra

and I spent five days in August 1999 backpacking through lush forests and

over rocky tundra as we made our way from camp to camp in the southeastern

corner of Glacier National Park. Camps in this park are designated, although

with enough paperwork, one can obtain a truly backcountry permit. Ours

was of the pseudo-backcountry kind: we had to hike, but there was an outhouse

there when we arrived, as well as designated campsites and cooking areas.

The trek began at 10 in the morning with a 20 minute boat ride across Two

Medicine Lake, a very deep (250 ft) dark blue oval shaped body of clear,

cold mountain water. The Lake was 2.5 miles across, and it saved us at

least that much hiking that first day. Not bad for $4. Plus, it was fun.

I donít get on boats very often. The boat docked on the western edge of

the lake, and let everyone off who wanted to get off (some appeared deathly

afraid of stepping off any man made surface). Andra and I were the only

ones without return tickets.

Andra

and I spent five days in August 1999 backpacking through lush forests and

over rocky tundra as we made our way from camp to camp in the southeastern

corner of Glacier National Park. Camps in this park are designated, although

with enough paperwork, one can obtain a truly backcountry permit. Ours

was of the pseudo-backcountry kind: we had to hike, but there was an outhouse

there when we arrived, as well as designated campsites and cooking areas.

The trek began at 10 in the morning with a 20 minute boat ride across Two

Medicine Lake, a very deep (250 ft) dark blue oval shaped body of clear,

cold mountain water. The Lake was 2.5 miles across, and it saved us at

least that much hiking that first day. Not bad for $4. Plus, it was fun.

I donít get on boats very often. The boat docked on the western edge of

the lake, and let everyone off who wanted to get off (some appeared deathly

afraid of stepping off any man made surface). Andra and I were the only

ones without return tickets.

The day was bright and sunny, with a few puffy

clouds dotting the deep blue sky: exactly as I had seen it in my dreams

since I made our campsite reservations 7 months before. My friend in Plant

Morphology tried making reservations two weeks after I had made mine, but

was denied. Apparently, you must reserve quite early for the choice sites.

Immediately after we hit the shore, I paused

for a few moments to invest in foot care. Moleskin that is. Very effective

stuff. I treat it as insurance against blisters, and I don't think I'll

every take a trip without it. Good stuff. The trail was made of dark brown

packed soil, with jungles of waist high ferns on either side. Most of the

way was sheltered by towering firs and spruces, but occasionally we came

into an area free of overhanging shadows, where flowers grew in abundance.

The trail led past a pinnacle of rock called Pumpelly pillar, named after

a well-traveled western geologist who explored many parts of the area.

We

passed several people along the way, more than I'd expected to encounter,

but most turned back when they reached Twin Falls, about a mile from the

lake. Twin Falls itself was tall, but at this dry time of year, not very

impressive. I have no doubt that in early summer it is a sight to behold.

We slowly crept upward toward Upper Two Medicine Lake and nibbled at huckleberries

and thimble berries along the way. Very tasty. Bears think so too.

We

passed several people along the way, more than I'd expected to encounter,

but most turned back when they reached Twin Falls, about a mile from the

lake. Twin Falls itself was tall, but at this dry time of year, not very

impressive. I have no doubt that in early summer it is a sight to behold.

We slowly crept upward toward Upper Two Medicine Lake and nibbled at huckleberries

and thimble berries along the way. Very tasty. Bears think so too.

Before we even had time to break a sweat, the

campsite appeared before us. We studied the diagrammatic map of the camp

layout: food hanging area-first right, food prep area-first left, latrine-second

right, four campsites, up to the left and toward the lake. We scouted out

each campsite one by one. I was a little dismayed to see how closely the

campsites were situated. Some good snoring could easily find its way into

every tent should the wind die down at night. I appreciate the park service

attempting to mitigate heavy tourist volume, but did they have to make

it like a KOA? I backpack partly because I can't stand to be around a dozen

other humans at a designated site, and walking five miles away from the

nearest road is your best chance to find yourself alone. Am I just cranky?

A curmudgeon at age 22? We had a nice afternoon reading in various places:

by the south shore of the lake on large rocks jutting out over the water,

on the north side of the lake on the gravel beach, in the tent, you know,

all the typical places of beauty. I was reading AIRFRAME, and Andra was

busily reading Palindrome. I found it hard to read at all with the natural

distractions. I just couldn't reconcile myself to traveling 700 miles to

sit in a national park and read a book. So I did little reading, and much

staring at the lake and the immense cliffs surrounding it. I threw

a line with a hook attached to the end into the water, but nothing came

to taste it. I am terrible at fishing, and that's probably why I stopped

purchasing a fishing license 3 years ago. Just not worth it. If I ever

figure up the amount of money in license fees I've paid for each fish I've

actually caught, I'm sure I will find those fish somewhere in the price

range of caviar. No license is required to fish in Glacier Park, so I fished.

We

ate pasta cooked over a white gas stove that evening in the designated

food prep area. I think it is designated merely to save the marmots the

trouble of walking from camp to camp to beg for food. This way, they can

solicit a larger audience with a fraction of the effort. Pretty sweet system

they got there. Watch your food, they're sneaky. Surprisingly, we were

the only group cooking. The other 4 groups contented themselves with jerky,

crackers, sausage and granola. Snackfood. I need something hardy, you know,

something with healthy doses of MSG and sodium benzoate.

We

ate pasta cooked over a white gas stove that evening in the designated

food prep area. I think it is designated merely to save the marmots the

trouble of walking from camp to camp to beg for food. This way, they can

solicit a larger audience with a fraction of the effort. Pretty sweet system

they got there. Watch your food, they're sneaky. Surprisingly, we were

the only group cooking. The other 4 groups contented themselves with jerky,

crackers, sausage and granola. Snackfood. I need something hardy, you know,

something with healthy doses of MSG and sodium benzoate.

I slept wonderfully that night, and awoke at 7:00

to try my hand at early morning fishing, although, admittedly, the prospect

of fish for breakfast didn't provide a lot of motivation. Nevertheless,

I stepped out of the tent after noisily getting dressed amid the tired

growls of my tentmate, only to find that dense clouds lined the valley,

obscuring the surrounding peaks and casting a cold gloom over the forest.

I suddenly missed my warm sleeping bag in the dark tent. I feared getting

back into the tent so soon, lest my tentmate find a weapon of some sort,

so I grabbed my pole and headed for deep water. After an hour of shivering

and freezing my butt off by the lakeshore, I hastened back to the tent:

I'm only a mountain man if the sun is shining, Iíll admit that. The clouds

were still low and gray, although every once in a bit I managed a glimpse

of the surrounding peaks through holes in the veil above. Back in the tent,

I warmed myself up in my bag, and the next thing I knew, it was 11:00,

and Andra was awake, reading her book. I panicked with the thought of having

to cover 6 miles and not even having gotten out of bed by 11. I hurriedly

got dressed and prepared oatmeal for breakfast. By this time the clouds

were gone, and the golden sun heated up the area real quick. We managed

to pack up and leave camp by noon, after which point my unease about getting

such a late start abated somewhat. It seems ironic that even on vacation,

I was concerned with keeping a schedule. If the Park Service allowed more

freedom to pick campsites, there would have been no sense of urgency. Camping

in national forests seems much more to my liking since you can camp wherever

and whenever you like....and it's free.

We backtracked the trail we had come up the day

before until we hit a Y intersection, and took the road not yet traveled.

We passed through more dense fern lowlands, very quiet and cool, and eventually

emerged from the forest onto a sharply sloped plain of tall flowers and

berry bushes, from which we could see that we were about a hundred feet

above Two Medicine Lake on the southwest shore. We continued to hike along

the lakeshore, gradually gaining elevation, until we reentered the forest

and the lake was lost from view. The huckleberries along this stretch

of the trail were especially numerous and delectable.

Glacier

National Park was created by Congress in 1910, and the bill was signed

into law by Teddy Roosevelt, the arch-conservative Republican who seems

to bear absolutely no resemblance to the arch-conservative Republicans

of today. Somewhere along the way the GOP dropped environmental stewardship

as part of their mantra, and thatís really too bad for everyone. The park

was first explored by prospectors looking for copper or oil. A copper mine

was started near Cracker Lake, and the Butte Oil Company continued to search

for the fabled oil reserves near Kintla Lake until 1912. Many Glacier Valley

was a mining town in 1900. Bailey Willis of the USGS took an interest in

correcting perceived errors in the US-Canadian border (49th parallel) that

was laid down in 1874, so he put together a team of geologists, paleontologists

and packers and set out to remark the border in 1901. Over the course of

three months, the team explored most of the northern section of todayís

Glacier National Park, and photographs Bailey took seemed to provide the

sensational advertisement necessary for Congress to create the Park. At

age 81, Willis declared that his photographs "played an important part

in the argument for a national parkÖ.back in Washington the photographs

taken by my good camera conveyed the beauty of the mountains and canyons

so vividly to President Roosevelt that he realized what the grandeur would

mean to the nation as a park for their enjoyment for all time to come."

Thank you, Mr. Willis.

Glacier

National Park was created by Congress in 1910, and the bill was signed

into law by Teddy Roosevelt, the arch-conservative Republican who seems

to bear absolutely no resemblance to the arch-conservative Republicans

of today. Somewhere along the way the GOP dropped environmental stewardship

as part of their mantra, and thatís really too bad for everyone. The park

was first explored by prospectors looking for copper or oil. A copper mine

was started near Cracker Lake, and the Butte Oil Company continued to search

for the fabled oil reserves near Kintla Lake until 1912. Many Glacier Valley

was a mining town in 1900. Bailey Willis of the USGS took an interest in

correcting perceived errors in the US-Canadian border (49th parallel) that

was laid down in 1874, so he put together a team of geologists, paleontologists

and packers and set out to remark the border in 1901. Over the course of

three months, the team explored most of the northern section of todayís

Glacier National Park, and photographs Bailey took seemed to provide the

sensational advertisement necessary for Congress to create the Park. At

age 81, Willis declared that his photographs "played an important part

in the argument for a national parkÖ.back in Washington the photographs

taken by my good camera conveyed the beauty of the mountains and canyons

so vividly to President Roosevelt that he realized what the grandeur would

mean to the nation as a park for their enjoyment for all time to come."

Thank you, Mr. Willis.

For the next few miles, we walked along in the

cool shade of the pines, meeting more people along the way, and growing

more annoyed by the incessant and arguably ineffective jangling of bear

bells tied to various parts of bodies walking past. We contented ourselves

to let everyone else scare the bears off, and saved ourselves the trouble.

As I had not bothered to put on any sort of deodorant, I anticipated the

bears would smell me coming long before I noted their proximity. Unexpectedly,

we came upon Rockwell Falls, a wonderful 30 foot rock ledge spewing water.

After hiking in the windless forest for so long, the cool mist spraying

out from the falls was very refreshing. We had our lunch there in the deep

shade by the rippling water.

The

trail got very steep after Rockwell Falls. We were by then anxious to get

to camp. We met an old German couple who claimed it was "only a few more

minutes to the lake", but 40 minutes later we were still wondering where

it was. Is that supposed to be encouraging, lying to someone about how

far it is? I'm not a big fan. Just a few hundred yards before we walked

to Cobalt Lake's rocky shores, dozens of people came down the narrow trail

from the lake, including a park ranger. We stood to the side while they

filed past, many of them stopping to tell us all about the two grizzlies

swimming in the lake a few hours earlier. Just missed them!

The

trail got very steep after Rockwell Falls. We were by then anxious to get

to camp. We met an old German couple who claimed it was "only a few more

minutes to the lake", but 40 minutes later we were still wondering where

it was. Is that supposed to be encouraging, lying to someone about how

far it is? I'm not a big fan. Just a few hundred yards before we walked

to Cobalt Lake's rocky shores, dozens of people came down the narrow trail

from the lake, including a park ranger. We stood to the side while they

filed past, many of them stopping to tell us all about the two grizzlies

swimming in the lake a few hours earlier. Just missed them!

Cobalt Lake was significantly smaller than Upper

Two Medicine. I say that as neither a compliment nor an insult. Every lake

we saw was beautiful in its own way. Cobalt Lake had a personality which

was more cold and barren. The shores were rocky and the trees growing about

the lake were small and stunted, owing to the proximity to treeline. The

southern shore consisted of a rock wall rising over a thousand feet above

the lake. On the shore, sitting in perpetual shadow, was a large field

of snow, with a curious hole near the bottom as if a bear might lumber

out at any moment. Did we really miss Grizz?

Cobalt Lake had only two campsites rather than

four, and the entertaining group of three that occupied the other site

regaled us at dinner with the story of their bear encounter on Two Medicine

Pass. Two Medicine Pass is at the top of the 1000 ft wall directly behind

Cobalt Lake. While trekking toward Cobalt Lake from the other side of the

pass earlier in that day, the group had been spotted by the two grizzlies

of previous fame, and were forced to leave the trail after being charged,

almost playfully it sounded, by one of the bears. Up on the pass, there

is no cover, no trees, no large rocks, and steep cliffs on either side.

I didn't envy their encounter, but I envy the story they'll be able to

tell friends back home.

The

next morning I awoke with very cold feet. I got up if for no other reason

than to put socks on, and stepped out of the tent. The sky was clear as

a bell, but the sun was still rising behind the 1000 ft wall that also

ran to the east of our camp. Anticipating the long hike ahead to Lake Isabel

on the other side of the pass, we got up and, moving quickly, made breakfast

and packed up camp all before 9:30. The sun had still not hit our camp

by then, and we walked in chilly shadow for the first ten minutes. The

trail climbed steeply to the west, and before long we stopped to change

clothes and rest in the last clump of stunted spruce until the other side

of the pass. The sun became very hot indeed as we labored up the ridiculously

steep slopes toward the pass. Often I found my boots slipping down on the

loose gravel, or my walking stick catching no grip as I leaned on it, so

steep was the angle of our ascent. It was laboriously slow going, and Andra

was in no mood for such hard work so early in the morning. We made our

way slowly up the west side of the ridge, and three hours later, we were

looking down on Cobalt Lake from a bird's eye view. We could even see our

campsite and the pit toilet. We continued along the ridge, noting with

a bit of disappointment the smoke-filled air. Fires were raging over most

of western Montana, with one near Kintla Lake inside the park to the northeast.

Visibility was severely reduced, and the sunlight filtered through in an

unnatural pink hue. From the top of the ridge, we could see Lake Isabel,

our destination, perched in a hanging valley not very far away. The problem

was that the hanging valley was not too much lower than where we were currently

at, but to get there, we first had to go the valley bottom 2000' feet below,

then come back up. I wasn' t the only one a little unhappy to see what

was in store.

The

next morning I awoke with very cold feet. I got up if for no other reason

than to put socks on, and stepped out of the tent. The sky was clear as

a bell, but the sun was still rising behind the 1000 ft wall that also

ran to the east of our camp. Anticipating the long hike ahead to Lake Isabel

on the other side of the pass, we got up and, moving quickly, made breakfast

and packed up camp all before 9:30. The sun had still not hit our camp

by then, and we walked in chilly shadow for the first ten minutes. The

trail climbed steeply to the west, and before long we stopped to change

clothes and rest in the last clump of stunted spruce until the other side

of the pass. The sun became very hot indeed as we labored up the ridiculously

steep slopes toward the pass. Often I found my boots slipping down on the

loose gravel, or my walking stick catching no grip as I leaned on it, so

steep was the angle of our ascent. It was laboriously slow going, and Andra

was in no mood for such hard work so early in the morning. We made our

way slowly up the west side of the ridge, and three hours later, we were

looking down on Cobalt Lake from a bird's eye view. We could even see our

campsite and the pit toilet. We continued along the ridge, noting with

a bit of disappointment the smoke-filled air. Fires were raging over most

of western Montana, with one near Kintla Lake inside the park to the northeast.

Visibility was severely reduced, and the sunlight filtered through in an

unnatural pink hue. From the top of the ridge, we could see Lake Isabel,

our destination, perched in a hanging valley not very far away. The problem

was that the hanging valley was not too much lower than where we were currently

at, but to get there, we first had to go the valley bottom 2000' feet below,

then come back up. I wasn' t the only one a little unhappy to see what

was in store.

We

continued on along the ridge, following the dotted line of the continental

divide on the map and summited 7700' Chief Lodgepole Peak. At that point

we had climbed 2800' from the shore of Two Medicine Lake. Interestingly

enough, we could see the parking lot where we began two days earlier to

the northeast 5.5 miles, and the furthest point of our trek, Lake Isabel,

3 miles to the southwest. Those distances are line of sight only; by foot,

we were much further away. From this perch, the surrounding peaks jutted

up clearly on the horizon. I love the names: Sinopah, Painted Teepee Peak,

Grizzly Mountain, Eagle Ribs Mountain, Mt. Despair, Appisoki Peak, Never

Laughs Mountain, Vigil Peak, Church Butte, Statuary Mountain, Red Crow,

Bearhead, Battlement Mountain, Caper Peak, Lone Walker Mountain, and to

the far north, the highest peak in the park, Rising Wolf. Dave and I once

had a discussion about why some mountains are named peaks and some are

named mountain, and furthermore, why some have Mount before the name, and

others have Mountain after the name. Our conclusion: whatever sounds best

goes. Pike's Peak sounds better than Mount Pike. And so on.

We

continued on along the ridge, following the dotted line of the continental

divide on the map and summited 7700' Chief Lodgepole Peak. At that point

we had climbed 2800' from the shore of Two Medicine Lake. Interestingly

enough, we could see the parking lot where we began two days earlier to

the northeast 5.5 miles, and the furthest point of our trek, Lake Isabel,

3 miles to the southwest. Those distances are line of sight only; by foot,

we were much further away. From this perch, the surrounding peaks jutted

up clearly on the horizon. I love the names: Sinopah, Painted Teepee Peak,

Grizzly Mountain, Eagle Ribs Mountain, Mt. Despair, Appisoki Peak, Never

Laughs Mountain, Vigil Peak, Church Butte, Statuary Mountain, Red Crow,

Bearhead, Battlement Mountain, Caper Peak, Lone Walker Mountain, and to

the far north, the highest peak in the park, Rising Wolf. Dave and I once

had a discussion about why some mountains are named peaks and some are

named mountain, and furthermore, why some have Mount before the name, and

others have Mountain after the name. Our conclusion: whatever sounds best

goes. Pike's Peak sounds better than Mount Pike. And so on.

As hard as the ascent up the pass was, the trip

down was even more difficult. My feet had remained blister-free up to that

point, but not even my friend moleskin could help my feet as they squished

and pushed against the toes of my boots on the steep switchbacks going

down for miles. I could feel the blisters forming on my toes and heels.

Try to ignore it. Eventually, after 4 switchbacks, we were back below treeline,

even though the majority of the trees were skeletal remains only. We ate

lunch in the shade of a few tall spruces and continued on the way down.

The

hike became more pleasant as the trail faded from stark, rock trails to

lush wet lowlands filled with ferns and huckleberries. All around

us birds sang, water crackled and whispered in the streams, and sunlight

filtered through the trees in patches, no longer quite so blotched out

by smoke. We stopped at the first water we crossed, having long since drained

our bottles, and filtered water. Plump tadpoles and anomalous grey, crusty

slow-moving "things" inhabited the water. It tasted very good.

The

hike became more pleasant as the trail faded from stark, rock trails to

lush wet lowlands filled with ferns and huckleberries. All around

us birds sang, water crackled and whispered in the streams, and sunlight

filtered through the trees in patches, no longer quite so blotched out

by smoke. We stopped at the first water we crossed, having long since drained

our bottles, and filtered water. Plump tadpoles and anomalous grey, crusty

slow-moving "things" inhabited the water. It tasted very good.

After awhile we were walking along a large creek,

several dozen feet above it, and were treated to nice aerial waterfall

views along the way. Without much fanfare, we passed into the Park Creek

campground at the valley bottom where the creek we had followed joined

Park Creek. A quaint old ranger patrol cabin sat at the trail marker, with

bright yellow NO TRESPASSING posters adorning every conceivable entry.

The trees here were enormous, and the surrounding vegetation was extraordinarily

lush. Without stopping to rest, we continued up the last leg to Lake Isabel.

Andra and I later talked about our favorite parts

of the trip, and I recalled that the hike up to Lake Isabel from Park Creek

was mine. The hike to that point had taken the better part of the day,

and we trudged up the overgrown mountainside of Vigil Peak in the late

afternoon sun. I love late afternoon sun in the summer, no time else is

the light so orange and warm. It bathed the leaves around us in orange

speckles, and sent shafts of bronze light streaking in all directions through

squinted eyes cast up at the horizon we were walking into. We were  exhausted,

but happy that we had come so far, over such elevation, and were now so

close. The pain seemed to melt away from my legs and feet, and we talked

quite a bit, in contrast to our silent trek over the pass. Like a dream.

In addition, we knew at that point that we were too far from a parking

lot to see anybody but the other people camping at the lake, which was

bound to be less than 2, and knowing how far from civilization and asphalt

we were lent a tang of barbarism to the whole event. Lovely thing to be

out in the forest far from anything. That was my favorite part of the trip,

right there. The paradox that flittered across my thoughts was that I enjoyed

the trail immensely, yet I was immensely anxious to reach the lake.

exhausted,

but happy that we had come so far, over such elevation, and were now so

close. The pain seemed to melt away from my legs and feet, and we talked

quite a bit, in contrast to our silent trek over the pass. Like a dream.

In addition, we knew at that point that we were too far from a parking

lot to see anybody but the other people camping at the lake, which was

bound to be less than 2, and knowing how far from civilization and asphalt

we were lent a tang of barbarism to the whole event. Lovely thing to be

out in the forest far from anything. That was my favorite part of the trip,

right there. The paradox that flittered across my thoughts was that I enjoyed

the trail immensely, yet I was immensely anxious to reach the lake.

Lake Isabel was much larger than Cobalt, and entirely

different. Trees grew right up to the shoreline, making strolls around

the lake difficult. The campsite was situated among an incredibly dense

thicket of huckleberry, cow parsnip and delphinium, and the individual

campsites themselves were spaced very far apart, much more to my way of

preference. A lone hiker was at the lake when we arrived, a Czech man named

Steven, not much older than I. He was on a six day trip through the park

alone, and seemed like a very nice man. Andra pointed out that perhaps

the reason I thought he was so nice was that he wasn't able to talk enough

(in English) to make me dislike him. Good point. It's hard to offend if

you keep your trap shut. He pointed out a moose wading in the water, and

we walked down to the shore to see, scaring it off in the process. We talked

little at the food prep area as we each cooked our meals, and it was a

very nice calm, quiet evening. The moment lived autonomously by that lake,

with the longest term goal being to hang up the food after dinner. Nothing

beyond the moment mattered, and that is a concept that simply can't coexist

with the soot-stained city life most of us are trapped in now. It was the

essence of simplicity: Smiles around the  hissing

cook stove, evening light, sitting on logs and sipping water with a meal,

the gentle lap of waves on the rocky shore, towering rock walls catching

the last light of the setting sun and blazing orange in a brilliant, luminescent

blue sky. All out here beyond the wall. Such stuff as dreams are made on.....mine

anyway.

hissing

cook stove, evening light, sitting on logs and sipping water with a meal,

the gentle lap of waves on the rocky shore, towering rock walls catching

the last light of the setting sun and blazing orange in a brilliant, luminescent

blue sky. All out here beyond the wall. Such stuff as dreams are made on.....mine

anyway.

We had no problem falling asleep that night. The

next morning came quickly it seemed, for I was not plagued by the usual

frequent awakenings I so often experience when camping. The light was shining

on the tent in spots, and another clear blue sky greeted us as we unzipped

the rainfly to peer out. We decided not to cook, since neither of us was

all that hungry, and instead snacked lightly on crackers and granola. This

allowed us to pack up camp and hit the trail earlier than usual, and we

parted from the shore of Isabel shortly before 9:00. My last view of the

lake was filled with rising fish on a plate-glass surface. If only I had

more time to fish!

Steven had left a quarter hour ahead, but we caught

up to him at the Park Creek Bridge, and then he disappeared from the trail

and had to have been behind us since I caught several hundred spider webs

in the face along the trail. The sky was not filled with smoke as it had

been the previous morning, and a steady wind cooled the sweat from our

backs (which left salt deposits that looked like bleach accidents). The

hike up to the pass was very difficult, but we were in better spirits,

so with frequent stops, we slowly made our way up through the  thick

underbrush, snacking on berries the whole way, and spotting the signs of

bears who had snacked on berries as well. We stopped at the last water

crossing to fill up before getting above tree line. Soon we were treated

to ever-more impressive views as we ascended higher up the ridge. I counted

the switchbacks as we went up, all seven, and was delighted to finally

reach the top of the ridge where we could finally look forward to downhill

(although, again, curiously, downhill is even more painful). We sat and

ate lunch on the top of the ridge with a panoramic view of the valleys

around us. The visibility was very much improved form the day before.

thick

underbrush, snacking on berries the whole way, and spotting the signs of

bears who had snacked on berries as well. We stopped at the last water

crossing to fill up before getting above tree line. Soon we were treated

to ever-more impressive views as we ascended higher up the ridge. I counted

the switchbacks as we went up, all seven, and was delighted to finally

reach the top of the ridge where we could finally look forward to downhill

(although, again, curiously, downhill is even more painful). We sat and

ate lunch on the top of the ridge with a panoramic view of the valleys

around us. The visibility was very much improved form the day before.

After a few more uphill pushes, we began the steep

downhill descent to Cobalt Lake. Toward the end of that trail, we became

very anxious to get to camp, and it didn't come soon enough. The tricky

thing there is that you can see the lake when you're still 2 miles away,

so it takes a lot longer than you think to get there. We rolled into camp

a lot earlier than the previous day, and by now we had our whole system

efficiently worked out. We grabbed everything we'd need for dinner, plus

our books, and went to the lakeshore, stopping to hang our food along the

way. An older couple rolled into camp and talked with us about how far

it was to the Park Creek Campground from here. Andra and I listened in

disbelief to their plans to continue on over the pass so late in the afternoon,

by then being nearly 5:00. As it had taken Andra and I 6 hours to make

the same hike, fresh, we were pretty convinced they had no chance of making

it before dark. As much as I hate unprepared backpackers, we invited them

to share our site for the night, and continue on in the morning (campsites

are reserved in advance, and they hadn' t done that). We lounged

by the lake and soaked our feet and legs in the icy water, and read our

books on this great large rock ten feet from shore that can only be accessed

by wading out to it. The sun shone low on the rocky horizon, glinting on

the waves of the deep blue water as the wind blew like a whisper across

the lake. My  attention

was more focused on the mosquitoes and mayflies hovering just above the

water in a wild circus of aerial acrobatics. The silence of the wilderness

is enchanting. It speaks to you, way down deep. Thoreau said most men live

lives of quiet desperation, but here is where you can escape.

attention

was more focused on the mosquitoes and mayflies hovering just above the

water in a wild circus of aerial acrobatics. The silence of the wilderness

is enchanting. It speaks to you, way down deep. Thoreau said most men live

lives of quiet desperation, but here is where you can escape.

Andra finished her book, and began reading mine,

which was fine since I was more interested in skipping rocks across the

water. I honed a new rock-skipping technique that is just diabolical. It's

all in the wrist, man. My rocks didn't just skip, they skiied on the water.

I took a walk around to the bear-hole in the snowfield on the south shore

and found I couldn't get to it without swimming. I also found out that

this little bear hole was large enough to drive a Honda through. Didn't

look that big from the other side. Amazing what a 1000' wall does to perspective.

We cooked dinner as the sun receded behind the

ridge to the west, and engaged in small talk with the unprepared hikers.

It was at this point that Steven rolled into camp. I was thinking he had

mentioned Cobalt as his next stop, but assumed that since he didn't make

it within 3 hours of us getting there I had misunderstood. I suppose he

just takes his time. He joined us in the kitchen and boiled some pasta

just like us. After dinner, Andra and I sat by the lake until after sunset,

then buried ourselves in warm sleeping bag goodness for the night.

I slept horribly that night. Thoughts of returning

to civilization or an unfortunately placed rock? Who knows. But it was

an endless night of restless dozing, and I was glad to see the tent lighting

up that morning. We had very little distance to cover that day, so we took

it pretty easy and slow. The other folks got up and out long before we

even packed up our tent. We sat by the lake for a bit and ate a leisurely

breakfast of pancakes before packing up and heading down.

We

stopped for a few minutes by Rockwell Falls on the way, but the call of

fresh sheets and a shower beckoned us down. I always find it strange how

when I'm in the woods, I want civilization things, and when I'm in "civilization",

I want backwoods things. I just can't shake my fickle human nature. We

last saw Steven sitting just beyond Rockwell Falls boiling water for tea.

How can you not like a guy of few words backpacking solo in the forest

and boiling water for tea by a waterfall? We plodded along at a good clip,

and as the day grew warmer, I began to have pain in my hips where the pack

rested. By the time we hit the parking lot, I was carrying my pack on my

shoulders only. My pack fits great, but five days is five days. I was happy

to take it off.

We

stopped for a few minutes by Rockwell Falls on the way, but the call of

fresh sheets and a shower beckoned us down. I always find it strange how

when I'm in the woods, I want civilization things, and when I'm in "civilization",

I want backwoods things. I just can't shake my fickle human nature. We

last saw Steven sitting just beyond Rockwell Falls boiling water for tea.

How can you not like a guy of few words backpacking solo in the forest

and boiling water for tea by a waterfall? We plodded along at a good clip,

and as the day grew warmer, I began to have pain in my hips where the pack

rested. By the time we hit the parking lot, I was carrying my pack on my

shoulders only. My pack fits great, but five days is five days. I was happy

to take it off.

I marched into the general store and purchased

two cans of Coca Cola, and after washing down in the restroom (man, how

the dirt did fly!) we sat under a tree on the beach of Two Medicine and

had a picnic. From the beach we could still see Two Medicine Pass, cloudy,

in the distance.

*****

The

remainder of the trip held much less adventure than the first. We sat in

the car that took us 30 miles north to Many Glacier Valley, only 30 miles

from Canadian soil. Our motel room was one of about 8 in a small building

in a compound of buildings cleverly spaced so as to seem almost cabin-like.

I enjoyed the room. No TV, no AC, no phone, no digital alarm clock. Perfect.

I happened to read in the welcome card that renovation was planned for

the entire motel to make it more modern. That's just what this motel needs,

absolutely. Someone is really using his head. Is it unusual that I am hard

pressed to find an example of something that mankind cannot make worse?

But I digress. We spent one evening in the motel room. Dinner was had at

the Italian Ristorante adjoining the motel lobby. The food was very nice,

and I enjoyed our window table for two, from which I could examine the

herds of tourists crowding around a telescope to see a mountain goat. It

is here that I learned definitively, from a college waitress from Washington

U, the real identity of huckleberries and thimbleberries (prior to that,

they were just good berries along the trail, discerned in conversation

only as "red" or "purple").

The

remainder of the trip held much less adventure than the first. We sat in

the car that took us 30 miles north to Many Glacier Valley, only 30 miles

from Canadian soil. Our motel room was one of about 8 in a small building

in a compound of buildings cleverly spaced so as to seem almost cabin-like.

I enjoyed the room. No TV, no AC, no phone, no digital alarm clock. Perfect.

I happened to read in the welcome card that renovation was planned for

the entire motel to make it more modern. That's just what this motel needs,

absolutely. Someone is really using his head. Is it unusual that I am hard

pressed to find an example of something that mankind cannot make worse?

But I digress. We spent one evening in the motel room. Dinner was had at

the Italian Ristorante adjoining the motel lobby. The food was very nice,

and I enjoyed our window table for two, from which I could examine the

herds of tourists crowding around a telescope to see a mountain goat. It

is here that I learned definitively, from a college waitress from Washington

U, the real identity of huckleberries and thimbleberries (prior to that,

they were just good berries along the trail, discerned in conversation

only as "red" or "purple").

Our last morning at the park was spent tromping

the well-worn paths to the south of Many Glacier Hotel, a Stratford-style

monument to 19th century opulence. The trails led to sites of interest

very quickly, and we dutifully photographed every lake and waterfall we

passed. The valley air hung like a cloth from all the smoke overhead, and

the sun filtered through in a reddish haze, if at all. Perhaps the sun

would not have seemed so dim had I more than an hour or two left in the

park. We headed back to the Italian Ristorante and had a pizza for lunch

before heading east out of the park, bound for southern skies.

*****

Imagery from

this trip location is available for sale in the Montana album at LandscapeImagery.com